There's been so much to think about lately. Our new war against ISIS. NFL players behaving badly. Scotland's independence referendum. The start of the fall premiere season on television.

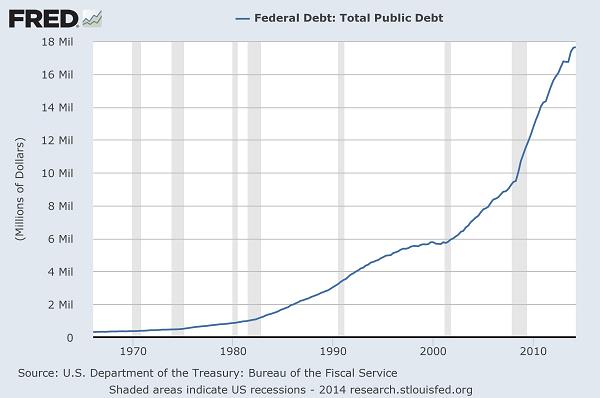

A year ago, it was all about Obamacare, the national debt, the never-ending deficit and the 16-day government shutdown. But as we head into the November mid-terms, fiscal conservatives will likely start grumbling about the fact that none of these problems were solved — they were merely kicked further down the road.

Related: The Threat That Could Scar the Economy for Decades

As things stand now, the national debt totals $17.8 trillion. That's nearly $56,000 for every man, woman and child in this country. According to the Congressional Budget Office's estimates, it's only going to get worse over the long run: By 2089 — admittedly a long, long, long, long, long time away — the federal debt will triple as the budget deficit grows from 2.8 percent of GDP now to a whopping 24 percent.

More bad news is coming as the Federal Reserve prepares to hike interest rates for the first time since 2006. The Fed's ultra-low interest rate policy has helped limit the pain for the ongoing budget deficit and growing national debt by limiting the damage from interest expenses. But with monetary policy on track to normalize, amid a strengthening in the economy and a tightening job market, the costs of carrying so much debt are about rise, attracting fresh attention to these divisive fiscal issues.

I want to nip in the bud the idea that this is all easily solved by raising taxes. The problem isn't a lack of tax revenue (which is expected to grow from nearly 18 percent of GDP now to 24 percent by 2089) but ballooning costs related to health care entitlements and growing interest on the national debt. Spending on these two items is expected to grow from 6.1 percent of GDP to 24 percent of GDP.

In other words, despite an already rising tax burden, the CBO projects that in 75 years all of America's tax revenue will only cover health spending (mainly on seniors) and interest on the debt. Everything else, from the national parks to the military to research and space exploration, will have to be funded by additional debt.

Related: A Bold New Plan to Fix the Retirement Savings Mess

Obviously, a lot of assumptions go into these numbers. Shortening the time horizon, and playing with the assumptions, reveals how quickly the situation could deteriorate. For one, the CBO follows current law in its baseline scenario. But that may not be realistic, since it assumes tax revenues rise dramatically, assumes the budget sequestration remains in place, and includes things like physician payment cuts that are repeatedly delayed (the so-called "doc fix").

This is where the Fed's interest rate hikes fit in. In the latest economic projections by individual Fed policymakers, the median expectation for short-term interest rates at the end of 2017 is 3.75 percent. Compare that to the CBO's estimate from August of 2.5 percent. For 2016, the Fed is at nearly 3 percent while the CBO is at 1.5 percent. For 2015, the Fed is just under 1.5 percent while the CBO is at 0.6 percent.

If CBO based its estimates on interest rate projections that prove to be too low, the effect on the budget outlook could be severe. More interest means more debt, which means more interest. How much more? Let's look at some numbers.

As noted by the Republican side of the Senate Budget Committee earlier this year, the CBO estimated that the country will spend $233 billion on interest expenses in 2014. Compare that to the $12.3 billion estimated to be spent on the Border Patrol this year, or the $10 billion on the Coast Guard, or the $8.3 billion for the FBI, or the $2.6 billion on the FDA.

Related: What Happens When the Fed Stops Propping Up Stocks?

Using some back-of-the-envelope calculations and the CBO's own estimates of the dynamics of the national debt under a higher interest rate environment, the federal interest expense could total an extra $650 billion over the next five years relative to the CBO's lower interest rate estimates. And the national debt will be nearly $700 billion higher than it would've otherwise been.

To bring this home, that's an extra $1,970 dollars for every man, woman and child in the U.S. over the next five years, bringing to bring the total per capita interest expense over this period to nearly $8,600. This is money the country won't see again, akin to the money spent on credit card interest.

The takeaway from this is that the national debt/deficit problem remains unresolved. As the subsidy from the cheap money printing ends, and with Republicans poised to potentially take control of the Senate in the mid-term elections in November, Congress and the White House will be forced to once again cross swords over issues like taxation, entitlements and spending.

Otherwise, the problem will only get worse as the debt and interest expense grows, threatening the dollar's status as the world's reserve currency and the Treasury's ability to respond to wars, disasters and any economic turbulence we may face in the decades to come.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: