Everywhere you turn the drama of the U.S. government is on television, and not just on the news. The American appetite for the chaotic mess that is our government has spread from 24-hour news channels to televised fiction. With juicy dramas like Showtime’s “Homeland,” Netflix’s “House of Cards” and ABC’s “Scandal,” as well as biting satires like HBO’s “Veep” and the gentler stuff of NBC’s “Parks and Recreation,” pols have replaced cops, doctors and lawyers as the go-to profession of TV protagonists.

This fascination for fictional politics is simultaneously a reflection of the growing ambivalence towards our political system, a view of transparent government fueled by the 24 hour news cycle and a culmination of a decades-long trend that has seen television become increasingly, explicitly political.

SLIDESHOW: 18 TV SHOWS THAT TOOK ON THE GOVERNMENT

Politics and television have historically been uneasy bedfellows. The so-called “Golden Age of Television” is often remembered for its sweet comedies such as the “Honeymooners”, but the prevalence of live broadcasts and the “newness” of the medium meant that controversial topics were often directly addressed. Even “I Love Lucy” forced its viewers to deal with the realities of life, when its star became pregnant, while shows like "Playhouse 90" staged powerful social dramas of the time. In order to prevent offending 1950’s viewers and, more importantly, advertisers stronger censorship measures were put in place to control what was shown on the tube.

By the 1960’s, as genre television became more and more prevalent, social politics found a firm footing in the medium. Dismissed by network censors as silly kid’s stuff, shows like “The Twilight Zone” and “Star Trek” (which famously featured television’s first interracial kiss) were quietly slipping messages of tolerance in between stories of gremlins and Klingons.

The 1970’s, feeling the aftershocks of the turbulent politics of the time, took a more direct approach to politics, working the conversations that now filled the nation’s dinner tables into “message comedies” like “All In The Family,” “Barney Miller” and, most notably, “M.A.S.H.” It wasn’t until the 1980’s, though, that the political machine itself really started to become grist for the television mill. Following Watergate and the various battles of the counter-cultural revolution, it became more difficult to see politicians as dignified statesmen arguing over what was best for the American people. Instead, politicians were often seen as corrupt, fallible and even buffoonish. Shows like “Benson” and “Hail to the Chief” (and then “Spin City” in the ‘90s) focused on beleaguered lieutenants who were trying desperately to hide from the world the fact that the emperor wore no clothes. Meanwhile, HBO was showing its ambitions with the edgy mocku-drama “Tanner ’88,” which followed a candidate as he ran for the Democratic presidential nomination.

THEN CAME SORKIN'S WEST WING

It was the 90’s where the current batch of shows really began to take shape, primarily molded by two pop-cultural behemoths of the day. With Bill Clinton in office, the image of the Commander-in-Chief was changing. Movies such as “Independence Day,” “Air Force One” and, most significantly, “The American President” made bank at the box office by presenting a young, dynamic, handsome and relatable view of the president. To misquote Henry V, the president “was but a man.”

The most entertaining parts of 1995’s “The American President” were the interactions among the White House staff. These weren’t just smart people talking about politics, these were smart, funny, passionate people talking about politics while simultaneously dealing with messy personal lives. Americans, increasingly college educated and concerned with work-life balance, could relate. And from the margins of Aaron Sorkin’s script, television history was made.

Sorkin’s “The West Wing,” which premiered in 1999, combined a transparent view of the nuts and bolts of policy with a Clintonesque optimism about the ability of government to make the world better. Centered on witty, articulate and photogenic characters, it was just soapy enough to keep users hooked, while being smart enough to bring in the critical acclaim. An entire generation of D.C. staffers has come of age citing this show as part of the reason they wanted to work for government. It’s hard to imagine a “Change You Can Believe In” campaign working without viewers being behind “Bartlett for America.”

The other show, while not explicitly about politics, certainly had a view of government that would shade our more cynical age. In an almost-reverse of the “Star Trek” model, “The X-Files” used a Watergate-shaped view of government as a labyrinthine organization full of dark secrets and darker intentions as a backdrop for a tense genre story. Borrowing its tone from the ‘70s paranoid political thrillers (“The Conversation”, “3 Days of the Condor,” etc.), “The X-Files” slogan “Trust No One” increasingly became the American attitude towards government.

Though both the “X-Files,” which started its run in 1993, and “The West Wing” would live on into the 2000s, neither could survive the political realities of the time. “The West Wing” could never quite reconcile the sunny liberal optimism of the Bartlett administration with the neo-cons running the show in the real post-9/11 world. As for “The X-Files,” alien conspiracies began to seem like an awfully fanciful concern when the threat of global terrorism was more clear and present.

POST 9/11 PARANOIA

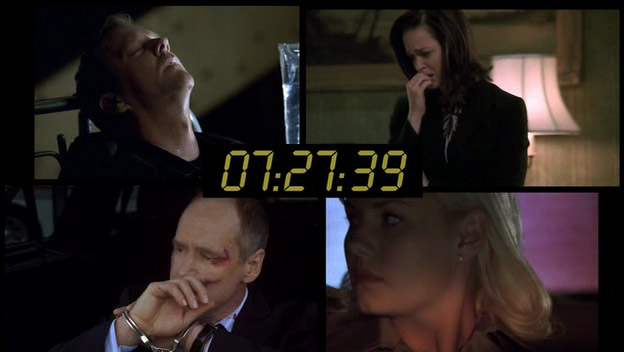

The age of terror needed its own show, and that show was clearly “24”. While taking its genre cues from cop shows and action movies, the politics of the show were always right on its sleeve: The world is full of people that would hurt this country, and only people willing to do whatever it took to stop them could save us. While the damage to Jack Bauer’s psyche was certainly explored, it was viewed as necessary collateral damage in the fight for security. This was the resolve required to beat a fanatical enemy. The Counter Terrorist Unit may have been full of monsters, but they were monsters fighting for us.

A decade later those scars were starting to show on our heroes, reflecting the ambivalence Americans felt about the tough choices and morally questionable decisions made in the name of safety. Sci-fi returned to its place as home for coded political critique, as campy ‘70s curiosity “Battlestar Galactica” was reinvented as a claustrophobic look at the exhaustion of perpetual paranoia. Even our Batman movies become dense meditations on the psychic damage of the war on terror.

“Homeland,” not coincidentally created and shepherded by two “X-Files” alums (Alex Gansa and Howard Gordon), shifted the focus from the action to the weight of the soul. While on its surface it’s little more than a gender-swapped “24” filtered through “The Manchurian Candidate,” the show relies less on the action set pieces of its predecessors and more on the crushing burden of knowing too much. Where Jack Bauer saw skeptical superiors as inconveniences to be ignored, Carrie Mathison must act as Cassandra, perpetually and prophetically correct but dismissed as crazy by the hierarchy. “Homeland” also takes an almost certainly more accurate view of the people that do the most to keep us safe: They’re not action heroes running around with guns, but rather data analysts with pages and pages of spreadsheets and reports.

Though considerably pulpier, the ratings success of ABC’s “Scandal” proves that the nation even wants their juiciest of ham to come from its highest office. Kerry Washington stars as a professional fixer who is hired by the White House to make sure that none of its dirty laundry is aired in public. Our current and previous administrations have largely avoided these types of salacious affairs, but sex is always the backbone of a good soap opera. While Clinton’s behavior was shocking (to some) in 1998, seemingly no amount of bad behavior from the White House would surprise a modern audience.

RELATED: 17 BEST POLITICAL MOVIES FOR OUR TIMES

The Netflix sensation “House of Cards” on the other hand, presents an almost “X-Files” like view of government (minus the aliens…probably). Using Richard III (and the original British version of the program) as a jumping off point, Majority Whip Underwood’s nefarious power plays in darkened corridors are presented as simply the way the game is played. Similar shows such as “The Good Wife” and the recently ended “Boss” both trade in this vision of government as a hotbed of intrigue and shady dealings.

Genre shows continue to sneak political messages into their created worlds. Behind its generous helpings of blood, sex and dragons, “Game of Thrones” is primarily a political show in which those with noble intentions are crushed beneath the wheels of money and power (poor, poor Rob). “Breaking Bad,” for all of its crime trappings, still contained a blistering critique of our modern health care fiasco.

But for all the cynicism engendered by our politics and reflected in our TV dramas, the experience of modern government that most Americans can relate to is less about blood-sport scheming, corruption or criminality and more about mundane, bumbling foolishness. In that regard, HBO’s blistering satire “Veep” presents a picture that seems a lot more like we’ve come to expect from our leaders. The show depicts a government full of pointless squabbles between petty, over-educated children who have little concern for the way their actions impact the lives of the people they are elected to (and paid to) serve. Anyone watching the events around the government shutdown can’t help but be struck by a sense of déjà vu.

As the behavior of our actual government becomes more and more absurd, our juicy potboilers and absurdist satires stop looking like fiction and start to look like a mirror held up to an ugly reality.