“I’m really dragging today. I’ve been having a hard time focusing and sustaining my body on a much slimmer calorie allotment than it’s used to. I made the mistake of creating a meal plan for the week that was heavy on carbohydrates and, as a result, I am feeling bloated and weak.”

The quote is from Ron Shaich, the CEO of Panera Bread, who is blogging on LinkedIn about his experience of living on $4.50 a day — the amount of money that the 46 million people in the U.S. get to supplement their income for food. Shaich made $4.4 million in 2012, but under his daily budget this week he can’t even buy himself a Panera sandwich.

The idea of going hungry in America is intolerable to most Americans, which is why the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as “food stamps,” was passed in the first place. The benefit, as Glenn Kessler notes, was meant to help recipients buy food, not be their only source of spending for it.

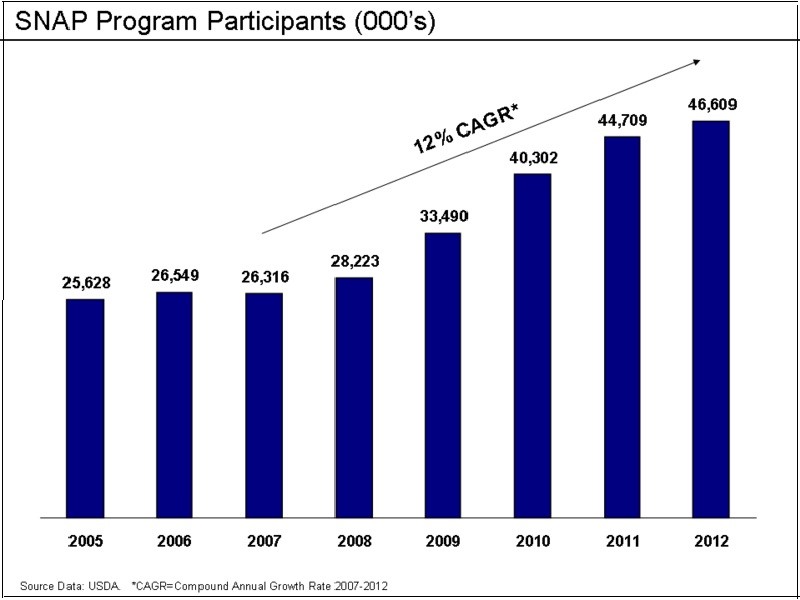

After eligibility requirements were relaxed, the program expanded dramatically. In 2001, SNAP served 17 million people at a cost of just over $15 billion. By 2012, 46 million people were enrolled in the program at a cost of a little under $75 billion. Like other government programs, demographics and economics are also driving the dramatic increase.

A story in the Washington Post last year claimed, “Lesser known is that college students are among the increasing numbers of people relying on food stamps.” Some students who get little support from unemployed parents no doubt deserve the benefit, as crushing student loans and dim job prospects conspire to thwart their futures. But almost any student who isn’t earning money can qualify for SNAP — whether their parents are millionaires or paupers. Unattributed reports of “food stamp parties” on campus have riled GOP lawmakers who believe the program has been compromised.

RELATED: PUZZLING RISE IN FOOD STAMP USE AS ECONOMY IMPROVES

Students alone, however, are not driving the dramatic change in food stamps. A new economic paper reported in The Wall Street Journal says the 70 percent increase from 2007 to 2011 correlates directly with local unemployment rates. The paper, published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, and written by Jeffrey B. Liebman and Peter Ganong, found that the enrollment spike resulted from the “program’s built-in automatic stabilizer features operating as usual in the midst of a very severe recession.”

Other economists say food stamp use lags after recovering from a recession. The Congressional Budget Office believes that SNAP use as a share of the economy will decline to mid-1990s levels by 2019.

This week, House Republicans plan a vote on a bill that would save $40 billion over ten years by restoring eligibility requirements that include ending waivers that allow able-bodied adults who don’t have dependents to receive food stamps. If passed, 3.8 million people would be eliminated from the program.