|

The eurozone has been heading down a slippery slope ever since its sovereign debt crisis erupted more than a year ago. The crisis so far has been a financial issue complicated by political bickering over a solution. It is entering a more dangerous phase. The debt problems are starting to weigh heavily on Europe’s economy, and the ripple effects are threatening global growth and the fragile U.S. recovery. The eurozone’s crisis is one more headwind that could tip the U.S. economy back into recession in 2012.

Economic forecasts for the 17-member eurozone are being cut sharply for the rest of 2011 and 2012, Ongoing fiscal belt-tightening and new stress on bank funding is tightening credit conditions even in the core German and French economies. Plus, many analysts now believe that Greece cannot escape a second debt restructuring with a much rougher impact on private-sector bond holders. The jolt would reverberate across Europe’s trade channels and bank balance sheets, increasing chances that financial contagion could engulf even healthy banks and solvent governments, as investors race to safer territory. U.S. financial markets and exports are also vulnerable, and new global uncertainty would weigh further on U.S. business investment and hiring.

Recent gauges of both activity and sentiment in the eurozone have plunged, suggesting the intensifying debt crisis has significantly damaged the economy. Analysts at J.P. Morgan, the latest to slash their eurozone outlook, expect real GDP in the region to slip into negative territory in the fourth quarter. They now forecast a decline of 0.5 percent in 2012, even assuming aggressive action by policymakers to support banks and sovereign obligations. A recession would put additional pressure on government budgets, add to the risk attached to government debts, further erode credit quality on bank balance sheets, and increase the chances of a global recession.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF), which lowered its forecast for 2012 global growth to 4 percent on Sept. 21, defines a global recession as growth below 3 percent. Many private-sector forecasts are already close to that mark. J.P. Morgan is at 3.1 percent, while Citigroup recently cut its projection to 2.9 percent. Nearly 90 percent of the investors, analysts, and traders surveyed in a Sept. 26 Bloomberg Global Poll say the eurozone economy is getting worse, while about two-thirds say the global economy is weakening. More than 40 percent of those polled expect a global recession in the coming year.

The eurozone slowdown, combined with the falloff in U.S. growth, is being felt around the world, especially in the high-growth emerging-market (EM) economies that led the global recovery from the last recession. Exports from emerging-market economies to the U.S. and eurozone accounted for more than 40 percent of emerging-market GDP last year. In the second quarter, EM export growth slowed to a single-digit annual rate, say J.P. Morgan global analysts, from a double-digit rate in previous quarters. The sharp slowdown in U.S. and eurozone growth suggests further slowing in coming quarters.

The new worry is China, whose largest trading partner is Europe. China’s economy is already slowing, as a result of past interest-rate increases aimed at reining in inflation. A global recession would raise the chances of a hard landing for the Chinese economy, which most analysts define as a sharp slowdown from the current 9 percent growth rate to 6 percent or less. China is already dealing with overly rapid credit growth, a housing bubble, overcapacity in its infrastructure, and heavy indebtedness of local governments—all of which could lead to more serious problems in a global downturn.

A sense of urgency about Europe’s situation was clear at the recent IMF/World Bank Annual Meeting. In addition to blunt talk by new IMF chief Christine Lagarde and other top finance officials, the IMF’s Global Financial Stability Report is especially sobering. It says that nearly half the 6.5 trillion euros ($8.9 trillion) of government debt issued by eurozone governments, most of which lies on the balance sheets of eurozone banks, is showing signs of heightened credit risk.

Given that exposure, Germany’s key vote last Thursday approving expansion of the European Financial Stability Fund (EFSF) up to the full 440 billion euros (nearly $600 billion) was important, but most analysts believe the fund is already too small and euro area politicians and policymakers are too far behind the curve in addressing the problem in a way that can contain contagion.

Analysts say policymakers must come up with a way to greatly expand the potency of the EFSF, possibly by leveraging the 440 billion euros to make additional loans and create new funds to recapitalize eurozone banks that come under pressure. But any such plan would encounter major political resistance because it would shift risk to eurozone taxpayers. “It requires convincing politicians to write a very large check with the argument that, in the end, the money will not be spent,” says Barclays Capital analyst Jose Wynne.

What would still be lacking, says Wynne, is a long-term “master plan” to help the eurozone economies grow back together instead of continuing to grow apart. Such a plan would require the right balance of fiscal austerity and pro-growth policies tailored to the strengths and weaknesses of each economy, he says. Politically and practically, that’s a daunting challenge, but without a credible long-run plan, says Wynne, “any financing program will be perceived by markets as only a temporary patch.”

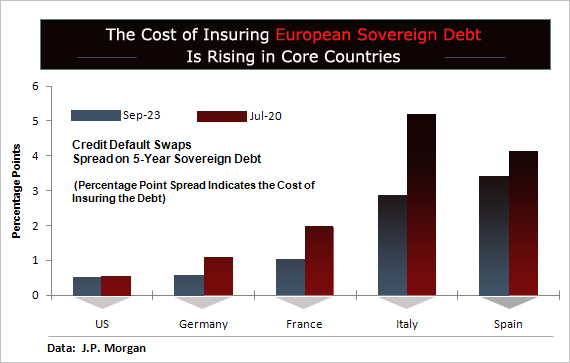

Meanwhile, the pressure on eurozone banks is mounting. The IMF report says that the market for credit default swaps, a kind of insurance on government and corporate debt, shows that market assessments of credit risk for banks have grown in lock step with the risk for governments. At the same time, falling stock prices have slashed the market capitalization of eurozone banks by 42 percent since January 2010, the IMF says, pressure that has intensified in recent weeks.

In a key sense, the U.S. and the eurozone share common problems—fiscal instability, political bickering, policy ineffectiveness, and a lack of much needed economic growth. Right now, neither economy seems capable of controlling its own destiny. It’s no wonder investors on both sides of the Atlantic have little confidence that a bad situation will turn around any time soon.