|

The recovery from the 2007-09 recession has been disappointing in many ways, but none as great as the chronically weak labor market. Two years since the recession’s end, the economy and job growth have slowed to a crawl, and the unemployment rate is rising again. You might wonder if Corporate America has even noticed. Corporate profits have posted one of their strongest recoveries on record, and stock prices have nearly doubled from their recession lows.

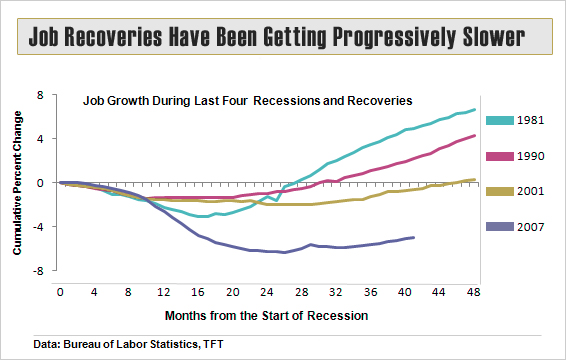

The disparity is an ominous sign that the U.S. job machine is seriously damaged. Profits have always been the crucial driver of business investment in equipment and other types of capital that generate economic growth and jobs. Yet, while the rebound in corporate outlays for new machines, high-tech gear, and software has been strong, hiring has not shown the typical benefits. The weak upturn in job growth partly reflects the recession’s severity and a sluggish recovery in overall spending, but much has to do with the dramatic change in the structure of the economy since the 1980s, which may have permanently raised the unemployment rate.

Some of the data are stunning. In May, only 64.2 percent of Americans 16 years and older were in the labor force, either working or seeking work, and just 58.4 percent were employed, levels not seen since the 1980s. Also, job growth in each recovery since the 1980s has been progressively slower. Perhaps most important, the relationship between the number of job openings and the unemployment rate, appears to have shifted. In the past, May’s 9.1 percent jobless rate would have implied far fewer job openings than now exist, suggesting that jobs aren’t being filled at the same rate as in the past.

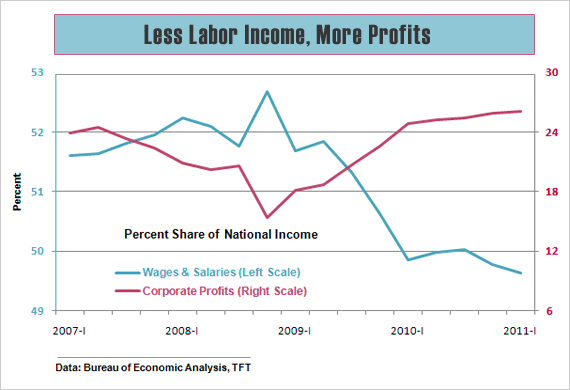

Over the years, U.S. companies have adapted to the new realities of global competition and technological advancements in well-documented ways that have lowered labor costs and lifted productivity, bolstering profitability. In the past decade these trends have accelerated sharply. Despite a lackluster recovery, corporations already have recouped 100 percent of their profits lost during the recession, and although the economy slowed in the first quarter, the average profit margin for U.S.-based nonfinancial businesses rose. More glaring, since the recovery began, profits have been taking an increasing share of national income, while the portion going to workers’ wages and salaries has continued to decline.

The push to bolster profitability has permanently altered the employment needs of many corporations, especially the mix of skills companies require. "We believe a large proportion of today's high unemployment is structural in nature, resulting from a huge skill mismatch between the jobs being created and the existing skill sets of jobseekers," says Wells Fargo economist Mark Vitner. The pressure from globalization is a driving factor. U.S. labor has become relatively more expensive compared with overseas labor, capital equipment, and computer software. The trend is discouraging labor intensive operations, Vitner says, while encouraging more capital-intensive industries, which require a much higher level of skills. Higher skills mean greater worker productivity, which boosts profits.

There are 23 unemployed construction workers for every available

job, with poor prospects for reemployment.

In an increasingly capital-intensive economy, many of today’s unemployed will be left behind. Based on first-quarter GDP, the U.S. was producing slightly more goods and services than before the recession—but with 7.3 million fewer workers, a point Wells analysts noted back in March. U.S. manufacturing is perhaps the best example of the shift. Compared with 1991, factory output is 55 percent higher, while factory employment is 32 percent lower. The jobs that remain typically require more sophisticated skills and more education. In May, the unemployment rate for college graduates was 4.5 percent. For high-school grads it was 9.5 percent, and for those without a high-school diploma the rate was 14.7 percent.

The severity of the recession has also added to this structural nature of unemployment, especially the disproportionate hit to construction. Over the past year there have been, on average, about 23 unemployed construction workers for every job opening, according to Barclays Capital, with poor prospects for reemployment in that industry or in other industries without retraining. Also, many unemployed homeowners cannot move to where the jobs are because the collapse in home prices has left them underwater on their mortgage.

Other factors at work include the record number of long-term unemployed workers, whose skills are eroding as a result of long separation from the job market. Extended jobless benefits, up to 99 weeks-worth in some states, also add to long-term joblessness and skill erosion by creating disincentives to seek work. Economists at both Barclays and Wells Fargo estimate that all these factors together have added at least 2 percentage points to the long-term unemployment rate.

Persistently high unemployment over the long run also puts

fiscal policy in a bind, especially when budget cuts leave

little room for job retraining.

If these estimates are correct—and there is still debate—policymakers may not be able to offer much help. Skill mismatches and other structural impediments to reducing unemployment are by nature long-term problems that cannot be cured simply by stimulative policies that boost demand. Given the severity of the recession, Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke in a speech on June 7 noted that “monetary policy cannot be a panacea.” Low interest rates cannot retrain or educate workers. Rather they tend to make capital even cheaper relative to labor.

Persistently high unemployment over the long run also puts fiscal policy in a bind, especially now when budget cutting at all levels of government leaves little room for programs that enhance workers’ education and skills. At the same time, structural roadblocks to reducing joblessness cut into the tax base, further exacerbating an already dire fiscal outlook.

It’s easy to criticize corporations for raking in profits while millions of workers go unemployed or underemployed. However, the bottom line is that companies have adapted to the changing structure of the U.S. and global economies a lot faster than the American workforce has, and a great number of those workers have a lot of catching up to do.

Related Links:

Biden Talks Stuck in Neutral as Job Market Crumbles (The Fiscal Times)

Jobs Crisis: Forget Ideology, Get People Working (The Fiscal Times)

How the Jobs Crisis Scars a Generation (New York Post)