|

The U.S. labor market has been looking stronger in recent months. Since jobs began to increase in early 2010, private-sector companies have added two million workers, with the overwhelming bulk of the gains coming from small businesses. So far this year, payroll increases have accelerated to a healthy 214,000 per month, the strongest four-month pace in five years.

But there’s a catch. The quality of the jobs the U.S. is creating right now in terms of pay, benefits, hours, and skills leaves a lot to be desired. The problem is not only the depth of the recession and the sluggishness of the recovery. It also reflects the changing structure of the U.S. economy, as more manufacturing operations shift to overseas locations, while service businesses, which often pay much less, take a more dominant role in job creation.

Previously high-paying jobs in manufacturing have gone the way of the Edsel. U.S. factories lost 3 million jobs from 2000 to 2004, jobs that did not return during the boom leading up to the recession, along with another 2.2 million from 2007 to 2010. Those are unlikely to come back, as well. Manufacturing jobs were 20 percent of private-sector payrolls in 1990, 15 percent in 2000, and just over 10 percent in April. Large multinational corporations have cut 2.9 million U.S. jobs over the past decade, while adding 2.4 million workers to their overseas operations.

More important, pay in manufacturing is not what it used to be. Hourly earnings of production and non-supervisory workers, which had held well above the private-sector average for decades, slipped below the average in 2006, and the ratio continues to trend gradually lower. In 2004, factory pay was about 3 percent above average. In April it was 2.4 percent below the $19.37-per-hour private-sector mark for production workers.

The recovery, so far, has generated a majority of lower paying jobs. Economists at UBS, who track payrolls in industries where hourly wages are above the overall average vs. sectors with pay below the average, say that job growth in low-wage industries has been generally faster since the recovery began in mid-2009. In particular, job gains in the retail-trade and leisure-and-hospitality sectors, where hourly pay is 32 percent and 43 percent, respectively, below the average for all private-sector employees, have accounted for 27 percent of this year’s job growth.

At the other end of the pay scale, and in addition to the 5.2 million jobs already lost, the recession wiped out nearly three million high-paying jobs in construction and finance, where average hourly pay is 11 percent and 20 percent, respectively, above the $22.95 average for all private-sector employees, which includes both production workers and management. Those jobs are not coming back any time soon, if ever. One bright spot has been professional and business services, including legal, accounting, computer systems design, and consulting. Jobs there typically pay 20 percent higher than average, and they have accounted for 30 percent of all private-sector job growth over the past year.

The big contribution to hiring by small business has been a blessing and curse. Since payrolls started to grow again in March 2010, companies with fewer than 500 employees have accounted for 97 percent of the growth in private-sector jobs, based on data from Automatic Data Processing. Companies with fewer than 50 workers have contributed nearly half, while growth at big firms with greater than 500 employees has been negligible. However, small companies don’t generate as much income per worker, as bigger outfits, and offer far fewer benefits.

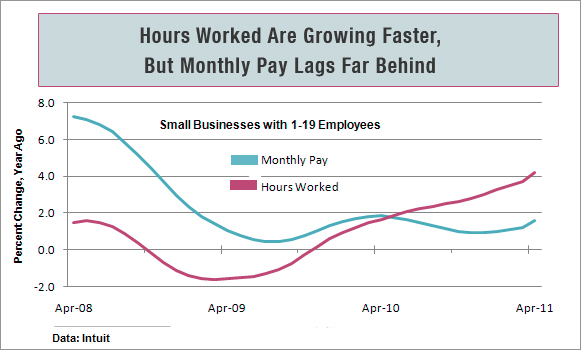

Small business hiring remained strong in April, but pay growth was sluggish, according to the Small Business Employment Index, developed by economist Susan Woodward with Intuit, a provider of payroll services for small and medium size businesses. The Intuit gauge covers companies with fewer than 20 employees, where employment has risen by 845,000 since October 2009, the company says, but over the past year average monthly pay has risen only 1.6 percent, to $2,653. “This upward trend is partly due to hourly employees working more hours while their hourly wages remain flat,” says Woodward.

Intuit’s measure of monthly pay translates to annual income of about $31,800. That is about 6 percent below the comparable measure for all production and non-supervisory workers in the private sector, based on Labor Dept. data for April. Intuit says the pay level reflects a lot of part time work at many small businesses. In the overall economy, 8.6 million people were working part time in April because they could not find full time work, little changed from the record levels over the past two years.

Benefits at small companies, as well as those for part-time and contract workers at large companies, are few and far between. Cost is the reason. The average annual cost of a family premium for employee-sponsored health insurance more than doubled from 2000 to 2010, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. More than 27 percent of workers in small businesses with fewer than 500 employees lacked any form of health insurance, the great majority of whom are in companies with less than 25 workers, according to the Small Business Administration. Nearly 72 percent of workers in small firms are not offered a pension or a retirement savings plan.

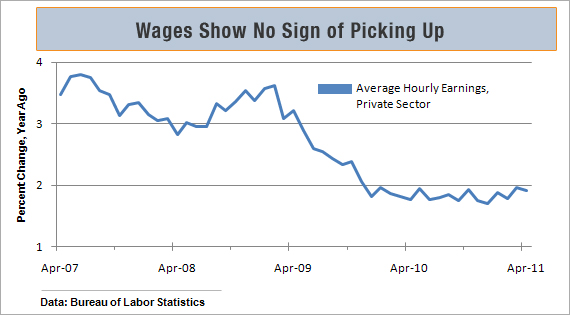

Given the unusually large slack in the labor force created by the recession, hourly pay across almost all industries is barely rising. Average hourly earnings for all private-sector employees in April were up only 1.9 percent from a year ago, according to the Labor Dept., close to the annual clip in late 2009 and below April’s 3.2 percent inflation rate. With 13.7 million people—9 percent of the labor force—officially unemployed and another 10.6 million either too discouraged to seek work or forced to work only part time, it’s going to be a buyer’s market for a long time.

An economic recovery will not by itself lift the quality of U.S. jobs. Economists know that workers are paid based on the value of the products they make and their contribution to a company’s production. That’s a long-term problem requiring policy efforts that support investments in research and innovation, as well as human capital, which reflects education and skills. Such efforts will be key considerations as policymakers battle over how to cut future budget deficits.

Related Links:

Stagnant Wages a Speed Bump for Economic Growth (Reuters)

Small Business News: More Jobs, Less Pay (Business News Daily)

Small Business Hiring is Steady but Slow (Yahoo Finance)