|

“A strong and stable dollar is both in the American interest and in the interest of the global economy.” It wasn’t surprising to hear that familiar refrain from Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke in response to a question during his first-ever press conference following last week’s Fed policy meeting. It’s a mantra ever since Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin first uttered it in the 1990s. Any official who publicly veers away from that message risks a misinterpretation of U.S. dollar policy and destructive volatility in the currency markets — especially now, when sentiment about the greenback is at a low ebb.

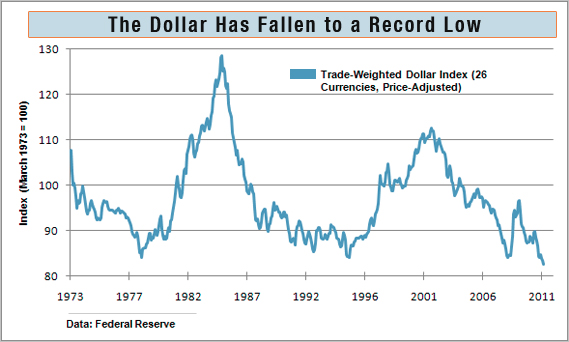

What Bernanke did not say is that based on the Fed’s trade-weighted average of 26 currencies, the dollar has broken through a record low going back to the end of the fixed exchange-rate system in the early 1970s, and there appears to be little fundamental support to prevent it from falling further. Many hold Bernanke and Fed policy, especially the second round of the Fed’s asset purchases — or quantitative easing known as QE2—accountable for the dollar’s decline. They fear an outright collapse in the currency’s value in foreign-exchange trading that could fuel U.S. inflation, jack up the cost of U.S. borrowing, and precipitate global financial turmoil.

There is no denying the downward pressures on the greenback, both in the near-term and over the next several years amid a changing global economy. But while the dollar is unlikely to bounce back strongly anytime soon, an outright collapse is not on the radar. That would require a complete loss of faith in the future of the U.S. economy and the policies that guide it, such that America would become an unattractive place to invest. Despite the dollar Cassandras and the challenges facing monetary and fiscal policy, the U.S. is still a long way from turning into Greece.

“It’s inevitable that the dollar’s role … will diminish from

the dominant world currency to one of a few.”

But looking over the long haul, a near-term rebound would hardly guarantee the dollar’s global dominance. “It’s inevitable that the dollar’s role … will diminish from the dominant world currency to one of a few,” hedge fund kingpin Ray Dalio told CNBC last month in a rare interview. Dalio, whose Bridgewater Associates is one of the world’s largest hedge funds, cited the contrast between heavily indebted developed nations, including the U.S., the euro zone, and Japan, and the rapidly growing emerging-market economies that now account for more than half of global growth. China now holds about $3 trillion of its currency reserves in dollars, but Chinese officials suggest they are aiming toward more diversification in their overall reserve holdings.

The dollar will need to be low enough to attract the foreign capital needed to finance large U.S. deficits both in trade and the federal government, a situation that, if not reversed, could add to downward pressure on the dollar while greatly increasing U.S. borrowing costs. Heavy government debt is a big part of the eroding U.S. net investment position, which reflects the faster growth of foreign-owned assets in the U.S. compared with the slower growth of U.S.-owned assets abroad. From 2004 to 2009, the latest available data, U.S. government securities held overseas accounted for 25 percent of the growth in foreign-owned U.S. assets, and last year global investors held 48 percent of marketable Treasury debt.

That means the ultimate fate of the greenback lies in the hands of U.S. policymakers, especially those now charged with reducing future budget deficits and restoring the health of the economy.

Right now, the dollar is doing exactly what economists would expect. In the short term, an economy’s currency is driven by expectations for economic growth and interest rates relative to other economies. Interest rates currently favor investments in other currencies, and the dollar must be cheap enough to attract enough overseas money to supply America’s huge funding needs.

The increased strength of foreign currencies make dollar-denominated assets like U.S. stocks, bonds, and many commodities that are priced in dollars, such as oil, more of a bargain for foreign investors. It also makes U.S. exports more competitive. On the downside, imports, especially oil and other commodities, are more expensive for U.S. consumers, which eats into household buying power.

Bernanke said the Fed is set to continue its easing policy through the end of June, keeping interest rates low as it increases the size of its balance sheet by completing its purchases of $600 billion in Treasury securities, and it plans to maintain that higher level of easier credit in future months. Meanwhile, central banks in Europe, China, and elsewhere are already lifting interest rates, and some are close to doing so, as in Britain, while others have put rate-cutting on hold.

The Dollar's Declines Since Initial Expectations of QE II | |||

Country | Currency | % Change Since | |

Australia | Dollar | -16.4% | |

Brazil | Real | -10.5% | |

Canada | Dollar | -9.6% | |

China, P.R. | Yuan | -4.3% | |

Denmark | Krone | -12.1% | |

EMU Members | Euro | -12.2% | |

Hong Kong | Dollar | -0.1% | |

India | Rupee | -5.2% | |

Japan | Yen | -3.7% | |

Malaysia | Ringgit | -4.3% | |

Mexico | Peso | -10.8% | |

New Zealand | Dollar | -11.3% | |

Norway | Krone | -13.9% | |

Singapore | Dollar | -8.8% | |

South Africa | Rand | -8.3% | |

South Korea | Won | -9.6% | |

Sri Lanka | Rupee | -2.3% | |

Sweden | Krona | -16.7% | |

Switzerland | Franc | -13.7% | |

Taiwan | Dollar | -9.7% | |

Thailand | Baht | -4.3% | |

United Kingdom | Pound | -6.0% | |

Venezuela | Bolivar | 0.0% | |

Sources: Federal Reserve | |||

The slowdown in the U.S. economy in the first quarter, to an annualized growth rate of 1.8 percent from 3.1 percent in the fourth quarter, suggests the economy is far from strong enough for the Fed to begin raising interest rates. Potentially more worrisome, the recent uptick in weekly jobless claims might reflect some degree of pullback in business hiring. Most Fed watchers don’t expect the central bank to begin increasing rates until well into 2012, a major reason for the weak dollar outlook. Only when U.S. growth prospects become firmly established in the minds of currency traders will the dollar begin to firm up.

Since the Fed chief first hinted at a second round of quantitative easing in a speech on Aug. 27, 2010, J.P. Morgan’s daily dollar index, which like the Fed’s gauge is trade-weighted and adjusted for price changes in each country, has fallen more than 10 percent. Since the U. S. recovery began, the index is down about 18 percent. Prior to the global recession, during which the dollar rallied strongly as a safe-haven investment, the greenback had been in a steady downtrend since peaking in 2002. Now, that long-term slide appears to have reasserted itself.

The bottom line is that the reverse of Rubin’s mantra is also true: A strong U.S. economy is in the best interest of the dollar. Policies that help to lift the economy will also help to strengthen the greenback.

Related Links:

U.S. Dollar Weakness and China Strength: Continuation Expected (Seeking Alpha)

Dollar Falls as Traders Expect Rates to Stay Low (ABC News)

Dollar’s Race to the Bottom (Wall Street Journal)