A U.S. business executive recently groused to me about a sizeable export deal that got away. The project involved supplying power generation equipment to a fast-growing country, and would have created a number of jobs in the U.S. Unhappily, the transaction had to be abandoned at the last minute when it developed that one of the deal’s signatories had required a bribe. Because of the strict (some would say onerous) terms of our Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA), which can throw a CEO in jail for approving pay-offs to foreign officials, the U.S. vendor walked away. Readers of this column, familiar with my frequent criticism of our government’s anti-business meddling, will be shocked that I applaud this outcome, notwithstanding its cost.

U.S. companies are undoubtedly disadvantaged by our FCPA. Though the OECD has encouraged adoption of similar rules among its members, enforcement has been underwhelming. Few of our competitors have been prosecuted for bribery; many dismiss our zeal for reining in graft abroad as yet another example of American naiveté. However, our effort to export U.S. standards of ethical behavior is not without merit, or without profit.

This issue is being debated today in the U.K., where the government has dragged its feet in implementing the U.K. Bribery Act, passed by Parliament last April. Ken Clarke, U.K.’s Justice Secretary, has made it clear that his first concern was to not “put a burdensome cost on legitimate business when coming out of a severe recession” — a message many of our own CEOs would love to hear. While sympathetic to those who argue that bribery is simply the currency of commerce in many countries, I like to think that of all our competitive weapons, this high bar we set may be among our most valuable.

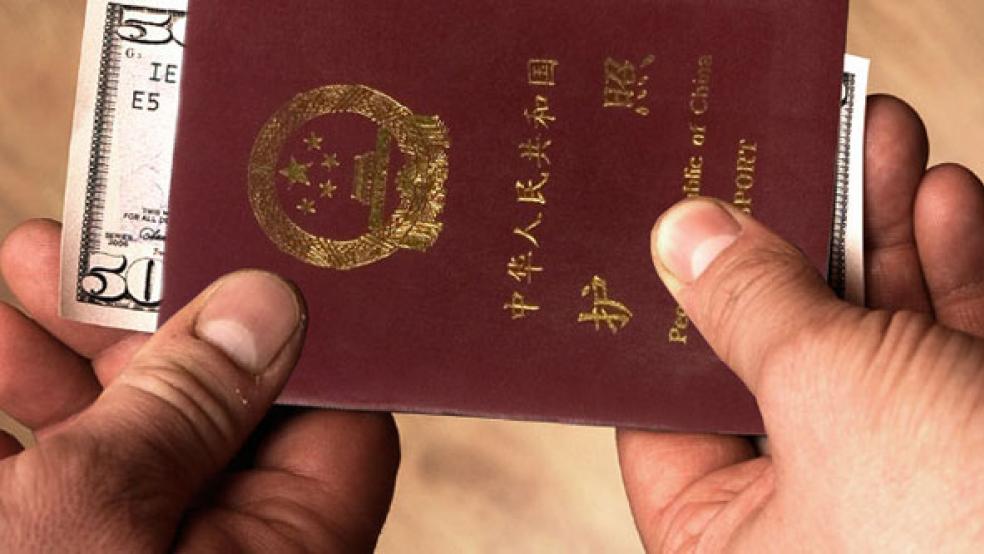

In particular, it distinguishes us from China. Some believe the Chinese will leap ahead of us, catapulted by their ambitious populace and forward-looking central planning. Pundits across the spectrum presume this change in the world order and extol the benefits of junior partnership. But I do not believe that a country engorged with corruption and reliant on wholesale thievery can ultimately succeed. The upheavals in Egypt and Tunisia were not inspired by higher prices and unemployment alone; the people of those countries were also rebelling against governments riddled with graft and dishonesty. It could happen in China, too.

We are so used to the pervasive dishonesty of the Chinese that it goes nearly unremarked. The theft of our intellectual property by that country has cost our industries billions of dollars and crippled our comparative advantage across scores of disciplines. China knocks off everything — our music, our apparel, our software, our drugs, our machinery — all under the noses of a government desperate to keep their people employed. Chinese individuals, purportedly encouraged by their officials, have hacked into the computers of our companies, our institutions and our government. To have Beijing agree after much prodding to cease using pirated software in government offices says in all. They don’t even pretend to play by the rules.

Ask anyone who has opened a factory in China. Almost certainly they will tell you that their obligatory local partner duplicated their joint facility a mile down the road, and quickly began to undersell them. Because the markets are so huge and because the Chinese want Westerners to continue to provide the know-how and technology to spur their growth, such undertakings are ignored and the cheating goes unchallenged. To some degree, Westerners admit to a grudging admiration for China’s chutzpah. In the end, however, it is not admirable or sustainable.

The false premise of China’s success is evident today. So concerned is the government about social unrest that the people of China are not allowed to watch the developments in Egypt; they are not allowed to convene peacefully to demonstrate for civil liberties. They, of course, are not permitted to celebrate the Nobel Peace Prize awarded to Liu Xiaobo. The government has become masterful in shutting down social network sites to limit protests. This repression cannot survive.

It is not easy (and not surprising) that the Obama Justice Department has aggressively prosecuted companies that fall foul of the FCPA. In 2007, fines collected under corruption investigations totaled $87 million. In 2010 the total passed $1.0 billion. In the midst of a recession one might hope that the administration would cut companies some slack, as is happening in the U.K. Still, maintaining our standards in times of stress is especially impressive.

For certain, U.S. businesses are often able to skirt the law. And yes, we have our fair share of dishonest activities in our corporate community. But, the very existence of this regulation says something important about the standards to which we will hold our corporations — and our political leaders — accountable.

What is that worth? For the United States, it is worth a great deal. It means that our citizens believe in the durability of our institutions. It means they have the confidence to save and invest for the future. It means that we have a basic trust in our government and in our political institutions. We may at times be frustrated and annoyed with our leaders, but we have guaranteed methods of voicing our displeasure.

This is what the entire world wants, and so few countries have. And yes, it does make us exceptional.