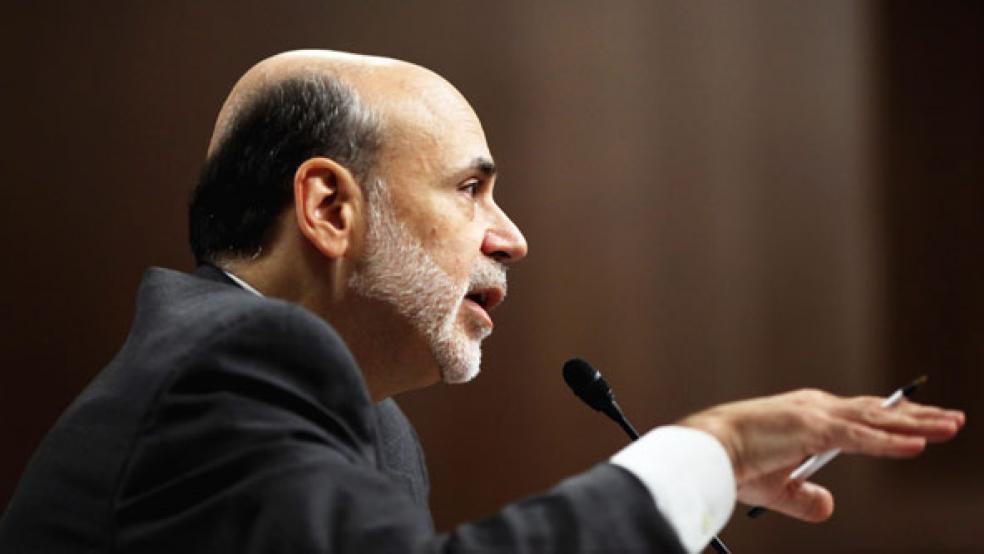

Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke faces a unique challenge—just when can he stop trying to save the economy?

For the past five years, the Fed has devoted itself to rebuilding from the wreckage of the financial crisis. It slashed interest rates to near zero and pledged to hold them there for years. It bought up Treasury notes and other bonds with three rounds of quantitative easing, the latest of which—known as QE3—costs $85 billion a month.

The markets have gone haywire guessing as to when Bernanke will finally pump the brakes. Some Fed watchers believe it could be as early as September, while others think the chairman will attempt to finish out his term without making any more waves.

After all, the economic picture now looks better with stocks having rebounded to pre-crash highs. But with GDP growth this year estimated to be somewhere in the 2 percent range, the economy is still far from phenomenal. And whittling down the Fed’s incredibly high $3.4 trillion balance sheet without disrupting the markets could be difficult.

RELATED: 5 MYTHS ABOUT THE FEDERAL RESERVE

Some answers are expected to surface on Wednesday, after Fed officials wrap-up their two-day June policy meeting, issue a statement, release new economic projections, and then let Bernanke field questions at the quarterly press conference he introduced.

“Bottom line, the Fed is in a no-win situation as I’ve said for years,” emailed Peter Boockvar, the lead portfolio manager for Morgan Stanley’s Excelsior Wealth Management, “the deeper they get with policy the more difficult it will be to extrapolate from it.”

When a Monday headline in The Financial Times said the Fed would “signal” plans to trim back its bond buying under QE3, the stock market instantly dropped (and later recovered). Investors figure the end of easy money—even months from now—will depress equity prices, even though the Fed will base any policy changes on improving economic data. Treasury note yields and mortgage interest rates have already surged in anticipation of the Fed ending its shopping spree.

Whatever choice the Fed makes will automatically invite criticism from someone. “That’s what Federal Reserve officials are underpaid for,” joked Edwin Truman, a former Fed staffer who now holds a fellowship at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Here are five factors to consider on Wednesday:

The Fed Cares About Jobs and Inflation —Our central bank has a two-pronged mandate. It is supposed to maximize employment and keep prices stable. All policy choices flow from this mission.

Investors have placed so much attention on the 10-year U.S. Treasury note, even though core inflation is what matters to Fed wonks. Since May, the 10-year Treasury yield has popped up by 53 basis points from 1.66 percent to 2.19 percent. This is supposedly in anticipation of QE3 ending.

“The Fed will focus on core inflation rather than the 10-year Treasury,” said Mark Olson, a former Fed governor who now works as co-chairman for Treliant Risk Advisors. “Watch for the Fed’s characterization of inflationary pressure when the statement comes out on Wednesday.”

On an annualized basis, core inflation was just 1.72 percent in April. That is slightly below the Fed’s 2 percent target. This would suggest that the economy is not overheating and that the U.S. can continue to push low interest rates to stir job growth.

The unemployment rate has fallen to 7.6 percent from a peak of 10 percent. Fed officials plan to keep their interest rates close to zero until it approaches 6.5 percent, an improvement expected to happen all the way out in 2015.

The Financial Times reported that some inside the Fed think the unemployment rate will drop if payrolls increase by about 200,000 jobs a month. The economy is already close to that, averaging 194,000 new jobs over the past five months. This would indicate that steady growth at this level makes it easier to taper off QE3.

Bernanke’s Possible Departure —After eight years as the Fed chairman, the Great Depression scholar is supposedly eyeing the exit come January.

Bernanke might want to hold off on tweaking policy until a successor is in place.

The favorite to replace him is Janet Yellen, who as the Fed’s vice chairwoman has been a key architect of the current policy. So if President Obama nominates her to be chairwoman, it would reflect a clear desire to follow the existing playbook.

Since the Senate must confirm whomever Obama nominates, this could be a difficult wait. Not all Republicans have been enamored by the bond purchases that they say will spark runaway inflation some time in the future.

But even if the new head of the Fed wanted to chart a different course, Bernanke’s ghost would be on his or her shoulder when debating policy that must approved by the 12 voting members of the bank’s Federal Open Market Committee.

“I think the current committee, with all the forward-looking communication, has to a large extent tied the hands of future committees when it comes to exit strategies,” said Roberto Perli, a former Fed staffer who now runs monetary policy research for Cornerstone Macro.

Pay Attention to the Economic Projections —Not to be too obvious, but Fed policy depends on what that data say. Changes to its economic forecasts will provide some insight into where the committee is leaning.

Stronger GDP growth means less need for Fed intervention, while weaker estimates indicate that QE3 might need to remain as is. These forecasts depend on how the government’s sequestration spending cuts are weighed, not to mention how the debt ceiling is resolved later this year.

When the Fed released its projections in March, the central tendency was growth in the range of 2.3 percent to 2.8 percent. This was slightly lower than what Fed officials predicted in December.

Markets Might Be Jumping the Gun —Stock and bond markets try to price in future events. Fed officials know this and expect that their communications will enable the market to do some of the work for them. This smooths the way for the Fed to adjust policy later on.

But the sentiment among many Fed watchers is that investors might be moving too early, since it could be several months before QE3 gets ratcheted down. Bernanke may shape his comments to reporters to argue that the market reaction—with the soaring bond yields—is a bit pre-emptive.

“My personal gut feeling—which is worth nothing—is that the market may be getting ahead of itself,” said the Peterson Institute’s Truman, noting the Fed is not “in the business” of generating volatility. “You don’t want to surprise the market too much or get it to react prematurely.”

“As far as the Fed is concerned, those fears of early rate hikes are misplaced,” said Perli. “The Fed is likely to actively push back against it through clearer communication of its intentions.”

Rebalancing the Fed’s Balance Sheet —At $3.4 trillion, the Fed portfolio has become massive. Profits from the bond purchases enabled the Fed to return $75 billion to the Treasury last year.

As the Fed unwinds its holdings, these returns would likely shrink and could potentially become losses that must then get absorbed by the Fed. This is the Catch-22 scenario. Too large a balance sheet leads to scolding by Congress, but losses from shrinking the balance sheet could also lead to heavy political criticism of a central bank that values its independence.

The Fed is “well aware” of this dilemma, said Perli. “Cost considerations are one more reason (in addition to a decent economy) that points to a slowdown of QE by September.”