When bombs exploded in Boston and a monster tornado tore through Oklahoma, paramedics and emergency medical technicians ran toward danger. As first responders, they put their own lives at risk in order to save the lives of others.

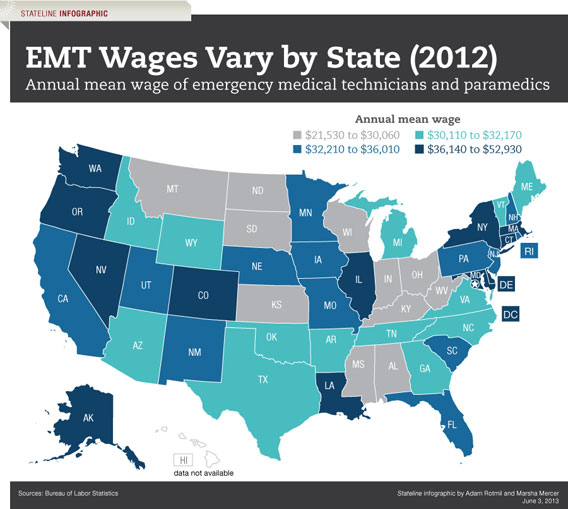

Yet EMTs and paramedics are governed by a haphazard patchwork of rules that vary widely by city and state. And their wages differ widely as well, from a high of $52,930 a year in Washington, D.C., to a low of $25,900 a year in Kansas. The national average wage was $34,370 in 2012, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. In smaller and rural communities, EMTs and paramedics are often volunteers.

In touch economic times, emergency services often are on the chopping block.

A survey of Emergency Medical Services leaders in the 200 largest cities found 44 percent had cut services last year, according to the Journal of Emergency Medical Services. It found 28 percent of big-city EMS agencies had a hiring freeze or were not filling vacancies, some for the third consecutive year. Fifteen percent reported layoffs. Twenty-one percent had no cost-of-living or pay-for-performance increases, some for the fourth year, the journal said.

RELATED: New York State Cops and Firefighters Get $100K Pensions

“Several states have made catastrophic cuts to state EMS offices over the last few years, causing reductions in staff,” said Dia Gainor, executive director of the National Association of State EMS Officials (NASEMSO). She singled out Alabama, New York and Iowa.

A recent investigation by the Des Moines Register found Iowa’s EMS system “broken.” Staff in Iowa’s EMS bureau has been cut 40 percent and its budget reduced by more than one-third since 2009, resulting in delayed inspections of EMS providers and less oversight, the paper reported.

Detroit’s EMS system has been “decimated” by layoffs, and other cities have had furloughs, layoffs and “rolling brownouts” in which a response office shuts down for a day, said Don Lundy, president of the National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians, a federal advocacy group.

Unlike public health, fire and police departments, emergency services are the new kids on the block. In the 1960s, a town’s mortician might respond to a car crash in a hearse. The federal government took a leadership role in the 1970s, developing the nationwide 911 phone system and establishing EMTs as a profession. But funding dropped dramatically in the early 1980s.

“Since then, the push to develop more organized systems of EMS delivery has diminished, and EMS systems have been left to develop haphazardly across the United States,” the Institute of Medicine reported in 2006. The report, “Emergency Medical Services: At the Crossroads,” described the nation’s EMS system as one of “severe fragmentation, an absence of systemwide coordination and planning, and a lack of accountability.”

BUREACRATIC CONFUSION

Even the number of EMTs and paramedics is uncertain. The Bureau of Labor Statistics said there were 232,860 paid EMTs and paramedics in 2012, based on its survey of employers.

In a 2011 report, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) said there were 826,111 certified EMTs and paramedics, based on a survey of state EMS officials. This number includes part-time, unpaid volunteers and those who receive stipends, as well as full-time paid staff. They work in a wide range of settings, including hospitals, clinics, law enforcement agencies, fire stations, oil rigs, Indian reservations, ambulances and air transport. NHTSA also said the BLS doesn’t distinguish between EMTs and paramedics and doesn’t identify EMS cross-trained as firefighters.

States with the highest number of paid EMTs and paramedics are California, New York, Pennsylvania, Texas and Illinois, according to BLS. The states with the highest concentration of paid emergency workers compared with the national average are Maine, Tennessee, Delaware, South Carolina and Kentucky. BLS economists said smaller states depend more heavily on paid EMS workers because they have smaller pools of volunteers.

“For a long time, EMS has been on the short end of the straw,” said Lundy of the EMTs association. He’s director of Charleston County EMS in S.C. and has been an EMT for 38 years. “A lot of communities don’t understand the true value the emergency medical service brings to the community.”

Until there’s a problem or crisis. Lundy cited Washington, D.C., which has been plagued with complaints about poor service and long wait times for ambulances. The city’s fire chief recently told the city council only 58 of 111 ambulances were in service, the city had only 245 paramedics (well short of its goal of 300), and some paramedics have responsibilities other than field work or responding to calls.

A key problem, Lundy and others say, is the lack of dedicated federal EMS funding. “As we stand here today, there’s no federal funding for EMTs, no grants for the local level. There are grants for fire services, and about 2 percent of that money may go for non-fire EMS grants,” he said.

RELATED: Why Everything You Know About Charitable Giving Is Wrong

“There are a lot of very dedicated volunteers who are funding their organizations through barbecue chicken dinners on Saturday nights,” Lundy said. “That’s very sad because they are on the front lines of the health care people get every day. If you opened a hospital and made the staff throw chicken dinners every week to pay the bills, people would think you were crazy.”

A dozen states don’t fund EMS at all, the National Conference of State Legislatures reported in a study last year. Federal grants are available for state trauma systems through the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the NHTSA and the Department of Homeland Security. Some of that money can be used for EMS. In addition, charitable foundations and corporations have become a source of revenue. For example, the Duke Endowment poured $5.5 million into emergency medical services in the Carolinas between 2004 and 2007.

“It’s an amalgamation of sources,” said Hollie Hendrikson of NCSL, who wrote the report on state trauma services. “Every state does it a little differently.”

Since the 1970s, when deaths from car crashes were a major concern, the Department of Transportation has housed an EMS office in NHTSA. Emergency services advocates are pushing for a lead federal agency for EMS, a need endorsed by the Institute of Medicine in 2006.

U.S. Rep. Larry Bucshon, R-Ind., a physician, introduced a bill in February that would set up an EMS office in HHS and provide EMS education and training grants. So far, the bill has just six co-sponsors.

Lundy hopes high-profile events like the Boston Marathon bombings will wake people to EMS needs. BLS estimates the need for paid paramedics and EMTs will rise 33 percent from 2010 to 2020, much faster than other occupations.

This article originally appeared in Stateline, a nonpartisan, nonprofit news service of the Pew Center on the States that provides daily reporting and analysis on trends in state policy.