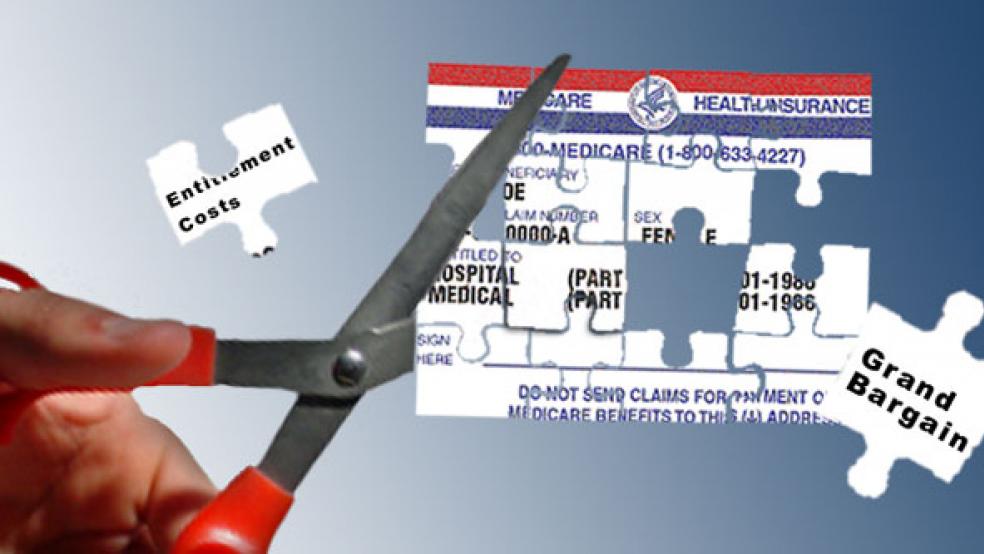

President Barack Obama's fiscal 2014 budget includes a variety of what he says are "manageable" changes for Medicare's 54 million beneficiaries as well as for the hospitals, nursing homes and other health care providers that serve them.

That assessment has drawn concern from some patient and provider groups that, although recognizing the need to address the nation's rising health care costs, say seniors shouldn't bear the brunt of efforts to reduce entitlement spending.

"Instead of making harmful cuts to Medicare or shifting additional costs onto beneficiaries, we need to look for savings throughout the health care system, including Medicare," said AARP Executive Vice President Nancy A. LeaMond.

Obama's budget proposal, which would reduce the growth in Medicare spending by $371 billion over the next decade, asks wealthier beneficiaries to pay more for coverage and future retirees to pay higher copays for outpatient services such as doctor's visits and home health care. But the gap in Medicare's prescription drug coverage where beneficiaries cover all the costs, known as the "doughnut hole,"would close by 2015, five years faster than current law mandates.

The president's plan would eliminate the two percent payment cut Medicare providers began to feel earlier this month as part of the automatic across-the-board cuts known as "sequestration." But hospitals and other providers would see their reimbursements reduced. Drug makers would be required to pay higher rebates for drugs dispensed to Medicare's poorest beneficiaries.

Obama's budget plan is far from the last word. House Republicans have approved their own fiscal 2014 blueprint, as have Senate Democrats. And many of Obama's Medicare proposals have been included in prior budget proposals that were not approved by Congress.

While Obama offered no surprises, "it's nonetheless significant that the president is once again recommitting himself to more than $4 trillion in deficit reduction built upon $400 billion in health program savings," said Eric Zimmerman, a partner at the Washington office of McDermott Will & Emery where his clients include hospitals, medical device makers and pharmaceutical companies.

What follows is a closer look at key provisions in Obama's fiscal 2014 budget that would impact Medicare beneficiaries and providers.

Higher Cost Sharing for New Medicare Beneficiaries:

In 2017, 2019 and 2021, new Medicare beneficiaries would have to pay an additional $25 for their Part B deductible, for a three-year total of $75 to be added on to the cost of the Part B premium, which in 2013 is $147.

Also starting in 2017, Obama's plan would require new Medicare beneficiaries to pay $100 for five or more home health care visits that are not preceded by a stay in the hospital or another medical facility, such as a nursing home or a rehabilitation hospital. Home health care is one of the few areas in Medicare that does not have cost sharing, and its rapid growth in recent years has led panels like the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) to recommend beneficiary cost sharing.

Beginning in 2017, new beneficiaries who purchase supplemental insurance, known as Medigap, with particularly low cost-sharing requirements, such as "first-dollar" coverage, will face a surcharge equivalent to approximately 15 percent of the average Medigap premium. The thought is that more generous Medigap plans encourage overuse of services, but seniors rely on these generous plans to shield them from unanticipated costs.

Joe Baker, president of the Medicare Rights Center, said that Medicare proposals that "increase deductibles and co-pays, and tax Medigap plans that ensure financial security, must be rejected."

Wealthier Beneficiaries Pay More:

Current law already requires individual beneficiaries whose incomes are $85,000 and above ($170,000 and above for couples) to pay a larger share of Medicare Part B (outpatient services like doctor visits and laboratory services) and Part D (prescription drugs) premisums. While most beneficiaries pay 25 percent of their Part B premiums, higher-income beneficiaries pay between 35 to 80 percent, depending on their income.

Obama's plan would increase the lowest income-related premium to 40 percent and cap it at 90 percent. His plan would also maintain the current income thresholds until a quarter of Part B and Part D beneficiaries are paying the higher income-related premiums. In a 2012 analysis, the Kaiser Family Foundation found that if the proposal to have a quarter of all beneficiaries pay the higher premiums were implemented last year, beneficiaries with incomes at or above $47,000 for individuals and $94,000 for couples would be paying higher income-related Medicare premiums. (KHN in an editorially independent program of the Foundation.)

The Obama administration says the proposal would help improve Medicare's financial stability by reducing how much the government spends on Medicare for beneficiaries who can afford to pay more. But the Center for Medicare Advocacy fears asking higher income people to pay a greater share of premiums "might lead to more people choosing not to participate in Medicare. Fewer participants in [Medicare] B and D would result in increased costs for the remaining participants."

Doughnut Hole Closing Faster, Higher Drug Rebates for Low-Income Beneficiaries:

Obama's budget plan would close by 2015, instead of 2020 as mandated by the health law, the "doughnut hole," that gap in Medicare prescription drug coverage where seniors pay the full cost of prescriptions until they hit a catastrophic cap. This acceleration would be financed by increasing the current 50 percent discount that the drug makers give to beneficiaries in the "doughnut hole" to 75 percent starting in 2015. Beneficiaries would be responsible for the remaining 25 percent of drug costs. Drug makers oppose raising the discount amount.

![]()

The president's proposal also alters drug costs for the nine million low-income Medicare beneficiaries who qualify for both Medicare and Medicaid. These people, known as "dual eligibles," used to get their drug coverage from Medicaid, the shared federal-state health insurance program for the poor and disabled. And drug makers returned back to Medicaid in the form of rebates part of the cost of drugs for those beneficiaries, just they do now for current Medicaid beneficiaries.

As part of the creation of the Medicare Part D prescription drug program, the drug coverage for "duals" shifted to Medicare. But the rebates that Medicare Part D plans negotiate are not as generous as those that drug makers previously paid to Medicaid, the administration says. Part D plans also pay higher prices for drugs than Medicaid does. The administration's proposal would require drug makers to pay the difference between rebate levels they now provide to Part D plans and the Medicaid rebate levels.

In a statement the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, said the rebate proposal would increase beneficiary premiums and copays.

Provider Cuts:

Hospitals are none too happy about Obama's plans to cut their Medicare payments for bad debt and graduate medical education over the next decade. Medicare now pays hospitals 65 percent of debts resulting from beneficiaries' non-payment of deductibles and co-insurance after providers have made reasonable efforts to collect the money. Starting in 2014, the president's plan would decrease that amount to 25 percent over three years, which the administration says would be closer to private payers that typically pay nothing on bad debt. The reductions would be in addition to those hospitals and other providers face as part of the 2010 health law.

Beginning in 2014, the Obama plan also would cut by 10 percent "add-on" payments to teaching hospitals for graduate medical education. In its budget document, the Department of Health and Human Services cites a MedPAC finding that these additional payments "significantly exceed the actual added patient care costs these hospitals incur."

Hospital groups, however, maintain that the cuts to bad debt reimbursement and medical education payments would weaken hospitals' ability to provide care and to train physicians, nurses and other health professionals.

Concerning payments to physicians, Obama's budget assumes that Congress will once again pass a "doc fix" to avert a scheduled 25 percent payment cut in 2014. Administration officials say they want to work with Congress to find a long-range solution to avert the annual crisis over Medicare physician payments.

What Obama Left Out:

The president did not propose an increase in the Medicare eligibility age from 65 to 67, a savings mechanism favored by the GOP but assailed by some key Democrats.

Nor did Obama propose combining the premiums beneficiaries pay for hospital care (Part A) and outpatient services (Part B). Taking that step, which has the support of Republican leaders like House Majority Leader Eric Cantor, R-Va., would reduce Medicare expenditures and lower beneficiaries' costs for hospital care. But seniors who mostly use Part B and don't go to the hospital often would pay more.

Some analysts wonder if these and other Medicare overhaul ideas could resurface as part of a larger discussion that includes overhauling the tax code and entitlements. "This is the first time in this presidency that I have seen a chance at a bipartisan budget agreement, so I am cautiously optimistic about that," House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan, R-Wis., told National Public Radio.

House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Dave Camp, R-Mich., has said his panel will hold a series of hearings to evaluate ideas including those advanced by Obama and by his fiscal overhaul commission. "Given the bipartisan support for various reforms to these programs, there is no reason we cannot roll up our sleeves and get this done," Camp said in a statement.

But the GOP and Obama have widely different views. House Republicans' fiscal 2014 budget plan, for instance, would eventually turn Medicare into a "premium support" plan that would give beneficiaries a set amount for their coverage, which Democrats oppose. Meanwhile, Obama has said he'll agree to entitlement changes only if Republicans agreed to higher revenues, which they steadfastly oppose.

This article, which originally appeared in Kaiser Health News, was produced by Kaiser Health News with support from The SCAN Foundation.