Every doctor knows that a patient recovering from a quadruple heart bypass is a poor candidate for elective surgery.

That’s the status of the housing market these days as tax reform advocates pound the pavement for putting the home mortgage interest deduction on the chopping block. With home prices and sales finally beginning to recover from the worst housing collapse in U.S. history, it would be asking for trouble to start tinkering with what every economist agrees is a major prop for home prices – the deductibility of interest on bank borrowings to buy homes.

“The housing market is still fairly fragile,” said Stan Humphries, an economist at Zillow.com. “Removing it altogether would be a shock to the housing market.”

“It would be painful for some time,” agreed Sam Khatar, deputy chief economist for CoreLogic. “Now is not the best time to do it because the patient is very weak.”

Yet there are plenty of reasons why redrawing the nation’s biggest housing subsidy program ought to be part of any serious program for reforming the nation’s tax code next year.

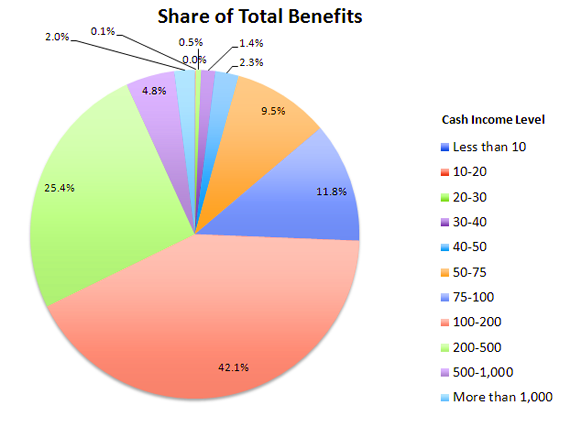

First, the home mortgage interest deduction flows mostly to the top half of the income distribution –the people who can afford to pay the mortgage, taxes, insurance and maintenance on a home. Households earning over $200,000 a year capture about a third of the $90 billion in tax benefits. Those earning between $100,000 and $200,000 captured another 42 percent of the benefits.

Meanwhile, households earning less than $50,000 a year – that’s nearly half of Americans since the median household income in 2011 was just $50,054 – received just 4.3 percent of its benefits or about $4 billion a year. This is the same group that is already taking it on the chin from the current Congress, which has cut direct housing assistance like public housing and subsidized rents by $2.5 billion a year, according to the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities.

The interplay of the housing market and the progressivity of the tax code skews the mortgage interest deduction’s benefits toward the well off. Though 63 percent of American householders own their own homes, most of those who don’t are in the lower half of the income distribution.

Among homeowners, wealthier people tend to live in larger homes in more expensive neighborhoods with larger mortgages, which require paying more tax-deductible interest. The median price for existing homes sold in July was $188,100. People who can afford larger mortgages are in higher tax brackets, so not only do they pay more, but each dollar of interest deducted is subsidized to a greater extent than the interest paid by a homeowner in a lower bracket.

For instance, a family in the 15 percent tax bracket that bought the median-priced $188,000 home with 20 percent down at current interest rates would receive about $2,700 off their taxes from deducting their mortgage interest. But a family in the 35 percent tax bracket that purchased a $1 million house with 20 percent down would receive about over $17,000 in tax breaks. Even if that wealthier household took out the same $150,000 mortgage as the median household (perhaps they are older with lots of equity from previous homes rather than being a younger first-time homebuyer), it would receive a $5,250 tax break – more than twice as much.

The deduction also encourages the nation to overinvest in housing, economists say. Though the total amount any household can take has been capped at $1 million since the 1986 tax reform, that still leaves plenty of room in most parts of the country for people to invest in vacation homes, take out deductible home-equity loans for remodeling or other purposes, and to bid up prices on desirable properties.

The deduction also serves to prop up home prices in good times or bad and that in turn props up the overall economy. Since homes remain most Americans’ most valuable asset, higher-valued homes tend to prop up other forms of consumer spending through what is known as the wealth effect. People who feel richer spend more.

National Association of Home Builders economist Robert Dietz estimates home values would be at least 12 percent lower without the home mortgage deduction. Removing it, he said, would wipe out nearly $2 trillion in household wealth."The indirect economic effects would be imposed on all homeowners through additional price hits,” he said. “Since we’re emerging from a balance sheet recession, reducing the value of peoples’ main asset – their home – would be a major mistake.”

Still there are plenty of ideas on the table for how to scale it back as part of tax reform. You could reduce the $1 million limit to $500,000, which would preserve it in full for most homeowners but penalize middle class people in high-cost cities; you could disallow the deduction for interest paid on home equity loans and second homes, although that would only raise about $8 billion a year; you could limit its use to first-time homebuyers; or you could, like President Obama proposed in his 2012 budget, cap the total amount of all tax deductions that high-income households can take, which would limit the amount of their home mortgage deductions without attacking it directly.

So far, homebuilders, realtors and mortgage bankers have successfully opposed any effort to scale it back. At a subcommittee hearing last year on the president’s proposal, Rep. Barney Frank, D-Mass., ranking member on the House Financial Services Committee, said “the mortgage interest deduction is going nowhere. The sun will go away before it does.”

About the only advocates willing to publicly support scaling back the home mortgage deduction are low-income housing advocates, who believe they are short-changed by current programs. They met with top White House officials Thursday to complain about the government’s slow pace of cleaning up the foreclosure mess. About 10 million homeowners have underwater mortgages and therefore can’t take advantage of today’s low interest rates to refinance.

But even they are skeptical about the benefits of reforming the deduction in the current political climate. “The biggest housing subsidy in America goes to middle and upper-income people, yet year after year the electorate backs cutting subsidies for low-income people,” said John Taylor president of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition. “If the money was used instead to support the homeless and undeserved people and to prevent foreclosures, I’d support its elimination. But if all it’s for is to increase the defense budget, then why bother?”