When President Lyndon Johnson signed Medicare into law on July 30, 1965, he touted the intended benefits of the program: “No longer will older Americans be denied the healing miracle of modern medicine,” he said. “No longer will illness crush and destroy the savings that they have so carefully put away over a lifetime so that they might enjoy dignity in their later years. No longer will young families see their own incomes, and their own hopes, eaten away simply because they are carrying out their deep moral obligations to their parents, and to their uncles, and their aunts.”

But for all the debate about reining in the costs of Medicare, a new study suggests that the mountainous out-of-pocket medical costs that patients pay during the last five years of their lives threaten the vision Johnson laid out.

According to the study, 43 percent of Medicare recipients spend more than the total value of their assets, excluding their home, on out-of-pocket medical costs. And 25 percent spend everything they have – or more than they have – including the value of their home. “Despite Medicare coverage, elderly households face considerable financial risk from out-of-pocket health care expenses at the end of life,” the study authors conclude.

Dr. Amy Kelley, an assistant professor of geriatrics and palliative medicine at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York, and colleagues at UCLA and Dartmouth analyzed the health-care spending and total household assets of 3,209 Medicare recipients during the last five years of their lives. The authors used data from 2002 to 2008 collected from the University of Michigan Health and Retirement Study, a government-supported survey of 26,000 Americans over age 50 taken every two years.

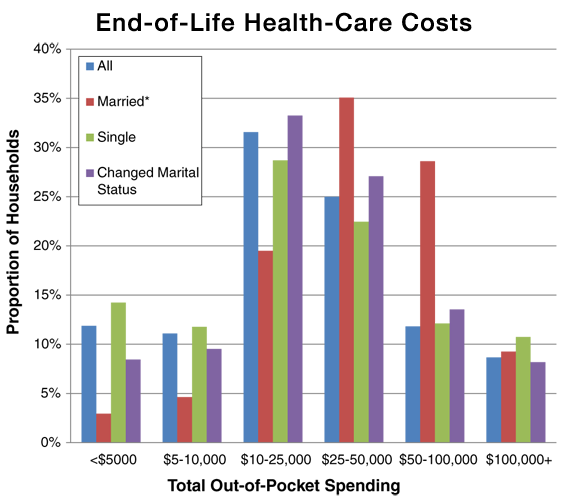

The study, published online in the latest issue of the Journal of General Internal Medicine, found that the median spending was $22,885, while the average spending for individuals was $38,688. For couples who endure the passing of one spouse, the average spending totaled $51,030. More than 75 percent of households spent at least $10,000, while the top quarter spent an average of nearly $102,000.

The levels of out-of-pocket spending varied greatly, with marital status playing a factor. Single people spent all of their remaining assets on medical care more frequently than patients who had a spouse. The cause of death also played a major role in determining costs. Patients with gastrointestinal or liver disease spent an average of just over $31,000. Those who suffered from Alzheimer’s disease spent more than $66,000 on average. Those disease-related differences make it harder for individuals to plan for their health-care costs at the end of life.

"Medicare provides a significant amount of health care coverage to people over 65, but it does not cover co-payments, deductibles, homecare services, or non-rehabilitative nursing home care," Kelley said in a statement. "I think a lot of people will be surprised by how high these out-of-pocket costs are in the last years of life."

Kelley and her co-authors warn that, while their study can’t predict end-of-life costs that will confront aging baby boomers, demographic trends and fiscal pressures to curb the growth of Medicare spending – along with the rising prevalence of dementia and debility – make it likely that out-of-pocket medical costs will keep going up. “As more baby boomers retire, a new generation of widows or widowers could face a sharply diminished financial future as they confront their recently-depleted nest egg following the illness and death of a spouse.”

For more on the costs of end-of-life care, read our e-book, Life at All Costs .