California's legislature easily passed a pension reform measure on Friday that cuts some of the most generous public employee retirement benefits in the United States, but even many supporters of the plan called it only a first step in fixing a pension deficit that has been decades in the making.

The pension bill, unveiled by Governor Jerry Brown on Tuesday after months of talks with fellow Democrats, will raise the retirement age and reduce benefits for new employees. It will also boost employee contributions and eliminate some practices that have led to exorbitant pensions for a relatively small number of workers.

The ability of a state government controlled by Democrats to defuse an issue that Republicans have seized on in Wisconsin and other states could have broader repercussions in the national debate over government fiscal policies.

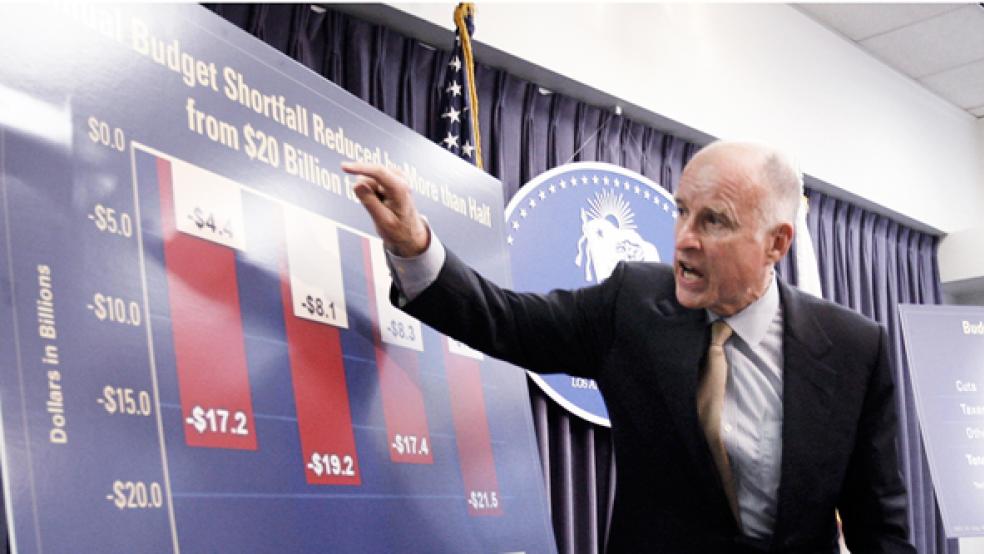

Passed on the final day of the legislative session before the fall elections, the pension bill is a key component of the state fiscal overhaul that Brown promised when he was elected to a third term as governor in 2010 -- decades after his previous terms in office. Brown hopes the pension measure will help persuade voters to support another pillar of his program: a tax increase on the November ballot.

The pension bill garnered strong bipartisan support in both chambers, passing 48-8 in the Assembly and 38-1 in the Senate, although supporters from both sides of the aisle said more was needed. "This is not something we're going to do overnight. We're going to have to work on this over the next several years," said Democratic Assembly member Jim Beall Jr.

TOO WEAK

Critics said the bill was too weak even when compared with the original proposal Brown put forward earlier this year, which included a "hybrid" pensions combining features of traditional pensions and 401(k)-style retirement accounts, for instance.

"The governor offered us a car," said Republican Assembly member Chris Norby, who supported the original plan. "This is more like a tricycle. It's never going to get us there."

State and local governments nationwide have been struggling to support lucrative public employee pension deals that were negotiated long before the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent recession took a huge bite out of tax revenues.

Pension costs have helped drive the California cities of Stockton and San Bernardino into bankruptcy court. Voters in San Jose and San Diego have approved measures to scale back pensions over the fierce objections of public employees, led by police and firefighter unions.

The state legislation approved Friday raises the minimum retirement age for most new state employees to 52 from 50. Safety workers, mainly police and firefighters, will in most cases still be able to retire as early as 50.

The new law also tames practices such as pension "spiking" that lead to higher payouts, and requires new public sector workers to split payments to their pension accounts at least evenly with employers. Current employees will be responsible for half their contributions, although some changes must be negotiated.

California's public pension plans are underfunded by hundreds of billions of dollars, although the extent of the problem is a matter of heated debate. The California Public Employees Retirement System (Calpers), the state's main pension plan and largest of its kind in the country, said the legislation would save $42 billion to $55 billion over 30 years.

Calpers, which manages pensions for state workers and for many cities and counties, pegged the present value of the savings from the new law at closer to $10 billion.

'BETTER THAN MOVING BACKWARDS'

Stanford University public policy expert Joe Nation, who has calculated Calpers' long-term unfunded liability at close to half a trillion dollars, said Brown's plan did little to solve the problem. "It's better than moving backwards, but this barely moves the ball forward," he said. Nation is a former Democratic member of the state Assembly.

Labor groups decried the bill as unfair to middle-class workers. "They are potentially subjecting a generation of workers to retiring into poverty or working until they die," said Terry Brennand, a government relations official with the Service Employees International Union. But some analysts saw the union protests as a tactical effort to boost Democrats' credibility as fiscal disciplinarians.

The November ballot measure, which would raise the sales tax and raise income taxes on high-income residents, has long been central to Brown's plans to restore the state's fiscal health. Approval would prevent further spending cuts, especially in education, in a state where the budget has been slashed repeatedly in recent years. It is strongly supported by teachers and other state workers.

The outcome of that vote could determine whether Brown's tenure is ultimately judged a success. With a Democratic majority in both houses, Brown has been able to get a budget passed on time. But tax increases in California require a two-thirds vote in the legislature or a voter initiative, and Brown failed to persuade any Republican legislators to support his tax plan.

If the tax measure fails, the state will be forced to make further Draconian spending cuts, and Brown, like his predecessor Arnold Schwarzenegger, could see his best-laid plans thwarted by an electorate that has little faith in state government.