Whether it’s by preference or an act of desperation by people who’ve gone years without a full-time job, U.S. workers are striking out on their own in greater numbers than ever before.

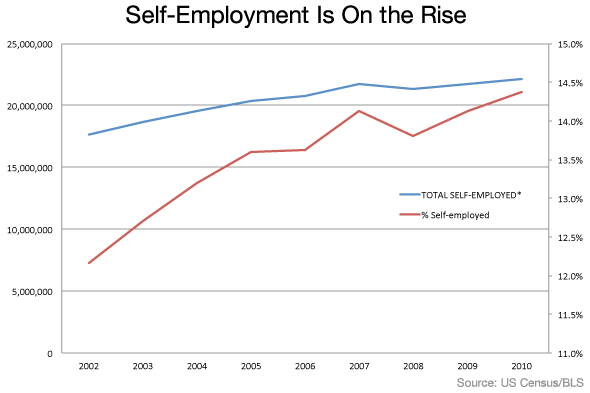

The number of Americans who consider themselves self-employed reached 22.1 million in 2010, up 414,000 from the previous year, according to the latest data from the Census Bureau. That represented 14.4 percent of the civilian labor force, more than two percentage points higher than 2002.

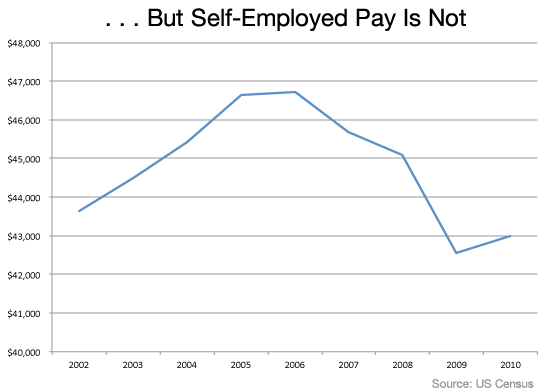

The average pay for self-employed people, however, has fallen sharply because of the Great Recession. The self-employed earned $43,003 in 2010 -- $3,721 less than average self-employment pay in 2006. As opportunities in better-paying fields like construction and real estate evaporated, people moved into fields like health care and social assistance; arts, entertainment and recreation; education; and “other” services like personal care and beauty parlors, all of which pay less than $30,000 a year on average.

“People who have been knocking on doors for two years will turn to something else when there are no payroll jobs in their field,” said Heidi Shierholz, a labor economist with the Economic Policy Institute. “The growth we’re seeing is in fields where you can create those opportunities.”

The increasing number of self-employed may be skewing public perceptions of the state of the job market, where progress is marked each month not so much by declines in the unemployment rate but by the number of new payroll jobs added to the economy. The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ monthly payroll survey does not capture self-employment.

The household survey, which gives the unemployment rate but is considered less reliable, does, but only if people report that they are self-employed. The Commerce Department numbers reported last week are based on tax records.

Changes that have swept through corporate America over the last several decades have driven the growth in self-employment, experts say. Companies that once provided the promise of life-time employment with good benefits for all their employees have increasingly turned to a system where a core group or managers, designers, marketers and researchers have full-time work while numerous support services are purchased on an as needed basis, often from individual contractors.

“We’re seeing much more of this two-tier workforce where there is a permanent group and a flexible workforce of contractors, consultants and freelancers who come in and deliver their services periodically,” said John Challenger, chief executive officer of Challenger Gray & Christmas, a worldwide recruiting firm based in Chicago. “It’s the polar opposite of being identified with one company.”

RELATED: Permalancing: The New Disposable Workforce

It is also usually the polar opposite in terms of pay and benefits. People who strike out on their own not only make less money than when they were gainfully employed, they often skimp on paying into their retirement accounts or skip buying health insurance. Vacations and holidays become luxuries that few can afford.

That’s especially true for blue, pink, and gray-collar workers who are forced into involuntary entrepreneurship because they can’t find full-time work. “It’s often temporary work by people fighting to hold on,” Challenger said. “In many fields, it’s low wage and an insecure way of bringing in a paycheck.”

Nearly a quarter million out of 2.7 million self-employed construction workers disappeared during the recession – and average pay for those seeking odd jobs with their tool chests fell by nearly $10,000 a year to $49,562. On the other hand, the number of people self-employed in “other” services like personal or beauty care rose by nearly 400,000 over the four years between 2006 and 2010, even as average pay fell $3,180 to $24,025.

The scramble to create self-employment has opened up new opportunities for consultants who teach people how to succeed at self-employment. B. Michelle Pippin of Women Who Wow in Chesapeake, Va., began her self-employed life 13 years ago doing administrative assistant work from home after the birth of her third child. Today, she has a flourishing practice teaching newly self-employed people how to earn money as an independent contractor in an increasingly competitive market.

“A lot of people think they have to just be good at what you do, but that’s not good enough,” she said. “What works is learning how to sell. You must feel comfortable asking for the sale. Say, ‘Which option is best for you?’ ‘When can we get started?’ You must learn how to close.”

But for most young workers, who are still in the skills-formation stage of their careers that will mean earning a lot less than when the economy provided full-time jobs with benefits.