The excesses that led to America’s economic malaise had little to do with politics. Gambling on unsecured derivatives based on triple A-rated bonds composed of subprime loans? It took Wall Street to bring down the house, or more accurately, houses—millions of them.

But the headwinds that are preventing the U.S. economy from fully recovering from the 2008-09 financial collapse are very much a product of politics. And those ill political winds are blowing from both sides of the Atlantic.

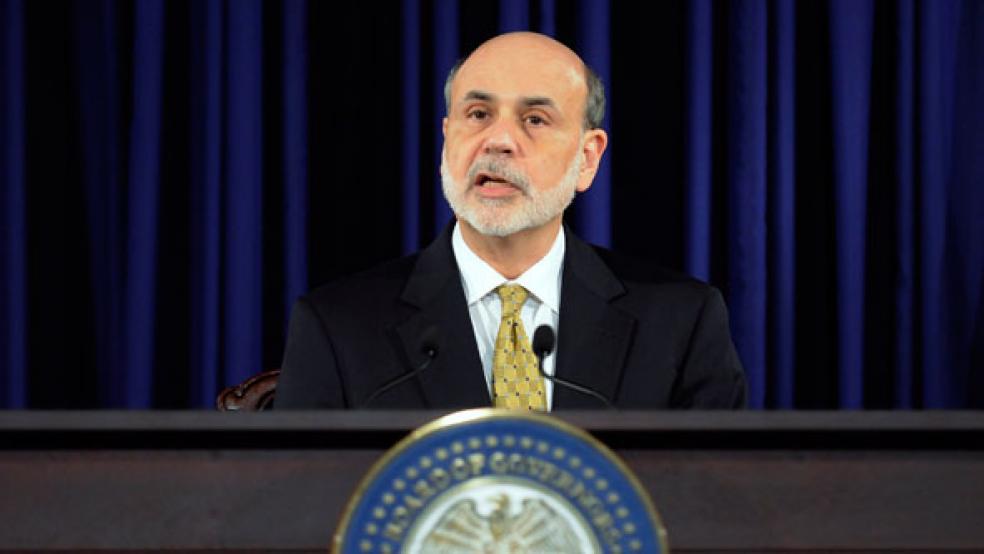

Federal Reserve Board chairman Benjamin Bernanke went to great lengths Wednesday to avoid criticizing U.S. politicians for their failure to deal with the so-called fiscal cliff that looms at the end of this year. On January 1, 2013, the economy gets hit with a 10-year, $1 trillion cut in the federal budget and an across-the-board tax increase triggered by expiration of the Bush-era tax cuts and the short-term payroll tax cut passed in 2010 to bolster the economy.

Most economists suggest the fiscal austerity that has already been imposed at the state and local level has shaved one percentage point off economic growth and kept the unemployment rate about one percent higher than it otherwise would be. An anti-stimulus package the size of the fiscal cliff would shave anywhere from 3 to 5 percentage points off economic growth. With the Fed predicting anywhere from 1.9 to 2.8 percent growth next year at best, that translates into renewed recession.

Bernanke noted the uncertainty swirling around the fiscal cliff had already caused some businesses to curtail activity and hiring, especially ones dependent on government contracts. He said as the year winds down, not knowing the shape of next year’s tax and spending policies will turn into a substantial drag on economic growth.

Yet, devastating as that would be, it wasn’t the most immediate political uncertainty weighing on Bernanke’s mind. Europe’s leaders, led by a recalcitrant Angela Merkel in Germany, have so far refused to deal with the flaws in their monetary union that were exposed by the collapse of government and housing debt bubbles in Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece and Spain – the so-called PIIGS. Whenever he was asked to explain why the Fed had reduced its economic forecast from two months ago, Bernanke immediately referred to the impact that Europe’s woes were having on U.S. businesses, especially exporters.

He admitted there was nothing the U.S. central bank could do to expedite the political solutions needed to put Europe on the path to recovery. He specifically ruled out purchasing European bonds, something the Fed can do legally. Unmentioned was the likelihood such a move would set off a firestorm of opposition from conservative critics on Capitol Hill who think the Fed has already done far too much bond buying in its efforts to keep interest rates low.

The Europeans “have adequate resources,” he said. “They are committed to addressing these problems. Keeping the European trading bloc together is crucial to the economies of those countries.”

It’s not as if the Fed has exhausted its capacity to aid the U.S. economy with a more expansive monetary policy. Yesterday it extended Operation Twist, where the Fed exchanges short-term bonds in its portfolio for longer maturity assets as a way of further lowering long-term interest rates.

But it could also embark on a third round of so-called quantitative easing (QE3), where it purchases financial assets from banks and other private corporations. The hope there is that those institutions will use the new liquidity to make more job-creating loans and investments. With unemployment stuck above 8 percent and projected to remain there through the end of this year, the Fed’s mandate to work toward full employment would certainly seem to justify more aggressive action now.

But the reality is that this last major arrow in the Fed’s quiver must be held in reserve in case political gridlock creates chaos on either side of the Atlantic. The U.S. circus won’t get underway until after the election since a divided Congress has no incentive to tackle an issue whose resolution might alienate their political bases while muting the differences between President Obama and Republican challenger Mitt Romney.

The European fireworks, on the other hand, could begin as early as the June 28-29 summit in Brussels. The crowded agenda for that meeting includes dealing with the immediate crises in Greece and Spain and launching the larger project of coordinating fiscal policies and forging continent-wide banking regulations, which are crucial to making the monetary union work. If Europe’s leaders fail to show progress, the eurozone could begin to unravel and financial markets across the globe could nosedive.

“There’s a lot of work to be done,” Bernanke said. “We’re hoping European policymakers take the steps” needed to restore growth. But “we’re prepared to protect the economy if the situation gets worse.”