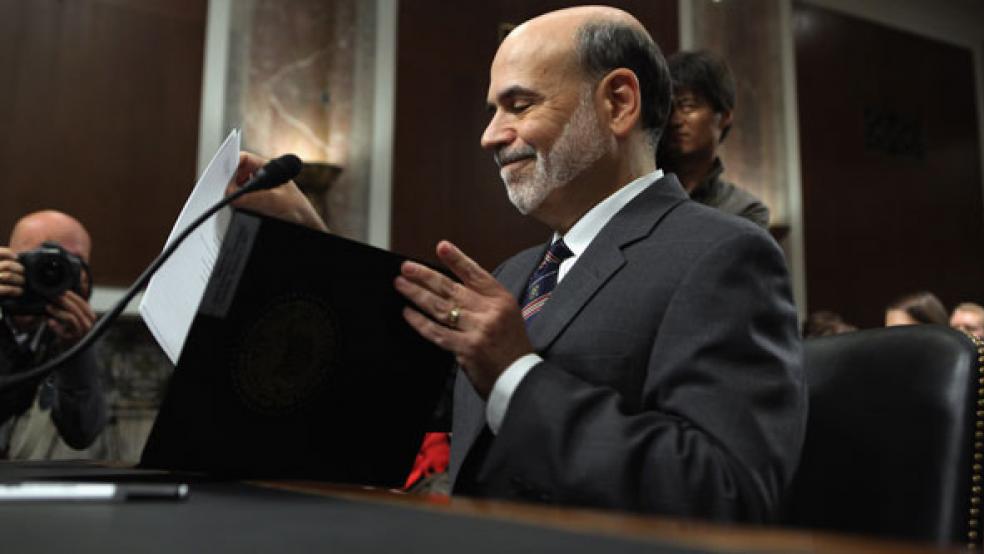

Federal Reserve Board chairman Ben Bernanke on Tuesday offered what amounted to a ringing endorsement of the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation, which Republicans running for president and on Capitol Hill have vowed to repeal should they win control of the White House and both chambers of Congress.

In a major speech at the annual economic conference of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, the Fed chief fired back at his critics by championing the Fed’s and other regulators’ crucial roles in staving off future financial instability. An overarching goal of central bankers, Bernanke said, should be to prevent panics like the 2008-09 collapse, which was caused by an out-of-control banking sector.

“Central banks certainly did not ignore issues of financial stability in the decades before the recent crisis, but financial stability policy was often viewed as the junior partner to monetary policy,” he said. “One of the most important legacies of the crisis will be the restoration of financial stability policy to co-equal status with monetary policy.”

Monetary policy – manipulating the supply of dollars to banks to raise or lower interest rates – was “too blunt a tool” to address the underlying issues that led to the recent crisis, like the housing price bubble and the build-up of huge private sector debt, Bernanke said. Rather, central bankers should have deployed regulations that “ensure adequate levels of capital and liquidity in the banking sector.”

Those rules could include varying caps on loan-to-value ratios on mortgages; requiring banks to maintain higher capital cushions against potential losses; and establishing margin and haircut rules for speculators, he said. Rules embodying those principles are in the process of being established under the 2010 reform legislation co-sponsored by former senator Chris Dodd, D-Conn., and Rep. Barney Frank, D-Mass.

“It does look like he’s going to bat for Dodd-Frank,” said Brad DeLong, a professor of economics at the University of California at Berkeley and a former deputy assistant secretary of Treasury in the Clinton administration. “It’s code for politicians to butt themselves out and leave policy to the technocrats.”

Bernanke’s championing of a renewed role for the regulatory side of Fed policymaking will further antagonize his critics on Capitol Hill and on Wall Street, where the same banking institutions that accepted bailouts during the crisis are now balking at the rules being put into place to prevent future meltdowns. At last week’s Republican debate in New Hampshire, most of the candidates on stage said they wouldn’t reappoint Bernanke, a Republican, to another term as head of the Fed when his current term expires in 2014.

Prior to becoming Fed chairman, Bernanke, then an economics professor at Princeton University, was a close student of the failures of the Fed’s monetary policy in the years after the 1929 stock market crash, which many blame for the Great Depression. His pointed reference to the Fed’s crucial role in preventing financial panics was a simple restating of the first principle of central banking, which was first articulated in the late 19th century by Great Britain’s Walter Bagehot but ignored in that crisis. Bagehot said that during panics, central banks needed to lend liberally at penalty interest rates.

Bernanke’s conservative critics question his following the first part of that principle: the bailouts themselves. They would have preferred, presumably, to let major financial institutions fail during a panic, which could have dragged the entire economy into a depression.

Critics on the left argue the long life of the crisis can be traced to the Fed’s failure to follow the second part of central banking’s first principle. “An awful lot more should have been done on the penalty rates,” said DeLong. “But Paulson [Henry Paulson, Treasury Secretary during the final months of the Bush administration] did not want to go there for ideological reasons; Geithner [Tim Geithner, the current Treasury Secretary] didn’t want to go there because he thought it would shake the bankers’ confidence; and Bernanke thought it should be left to the politicians.”

Given the level of non-performing loans on the banks’ books, the “penalty rate” would have been a takeover of the bad loans, wiping out stockholders equity, and infusing the banks with new capital. It would have amounted to a temporary nationalization of the banks, which could then have been sold off to new investors.

Failure to deal with the bad debts merely prolongs the crisis, DeLong said. “It looks like Europe is about to make the same mistake.”