If there is one issue that unites President Obama, lawmakers from both parties, business executives, and taxpayers it is this: Taxes—both individual and corporate--need a major overhaul.

That's where the agreement ends.

As Congress and the administration debate what’s needed and Presidential candidates like Newt Gingrich, Tim Pawlenty, and Herman Cain roll out their plans, proposals to overhaul the tax system are proliferating like kudzu. Many say it’s unrealistic to expect new legislation before the 2012 presidential election, but things happen unexpectedly in Washington, and growing concern about America’s debt and deficits is moving a rewrite of the Internal Revenue Code off the back burner.

The outcome will have an enormous impact on American business as well as individuals. “It’s a debate to watch carefully,” says Hank Gutman, a tax principal at accounting firm KPMG and former chief of staff of the Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation. Business leaders especially “need to be in a position to be nimble in order to react.”

Nearly all of the chief executives, economists and tax experts who shared their ideas about corporate tax reform with The Fiscal Times called for a reduction in rates to make the U.S. more competitive globally. But many also noted that it would be difficult to consider corporate tax reform in a vacuum, and any overhaul should be in the context of a broad look at how companies and individuals are taxed.

“There is no one reform that will galvanize the support needed to achieve tax reform,” said Marty Regalia, chief economist and senior vice president for economic and tax policy at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. “Broadening the base and cutting marginal rates are key, but since about half of business taxes are collected from pass-through entities under the individual code, reform must be comprehensive. Either group likely has sufficient firepower to derail the process if they are left out.”

Many businesses, big and small, are "pass-through" entities, which means their profits or losses flow through to the owners and are taxed at the owner's individual income-tax rates. Among these are sole proprietorships, limited-liability partnerships, and limited liability corporations.

The corporate tax rate tops out at 35 percent and when combined with state income taxes can reach just over 39 percent, the second-highest rate after Japan among members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. But there are loopholes that allow some companies to pay less or next to nothing.

With the federal budget deficit for the first eight months of fiscal 2011 approaching $1 trillion, according to the Congressional Budget Office, the focus is on making any plan “revenue neutral,” that is offsetting a lower rate with increased revenue from other sources. Last December, President Obama’s Fiscal Commission—led by former Wyoming Senator Alan Simpson and former White House Chief of Staff Erskine Bowles--proposed cutting the federal rate to 28 percent by eliminating what are known as “tax expenditures,” provisions in the tax code that keep companies’ effective rates low. House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Paul Ryan, R-Wis., and Dave Camp, R-Mich., have called for reducing the rate to 25 percent. A proposal earlier this year from Senators Ron Wyden, D-Ore., and Dan Coats, R-Ind., would set the federal corporate rate at 24 percent and repeal a number of business tax benefits.

Some corporate executives, and others, want to cut the rate even more. “The combined U.S. federal and state tax rate should approximate the average OECD tax rate of 25 percent,” Bob Iger, president and CEO of Walt Disney Co., said in an email to The Fiscal Times. “The incentive for transferring intellectual property outside the U.S. and shifting income to low-tax countries through aggressive pricing of intercompany transactions would be greatly diminished.”

“A lower rate, particularly on the order of 20 percent on the federal level would solve a multitude of problems,” said Pam Olson, a former Assistant Treasury Secretary for Tax policy who is now a tax partner with Skadden, Arps in Washington. “It would take away some of the incentives to move operations overseas,” she added. Under the current tax code, multinational corporations can reduce their effective tax rate by shifting operations overseas.

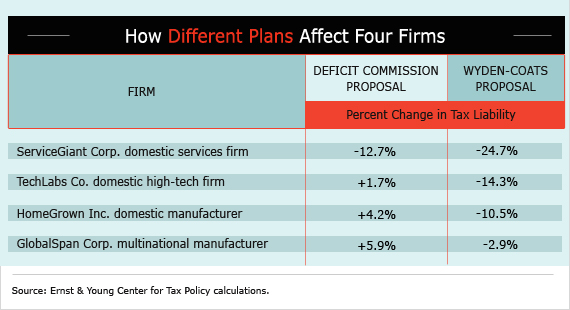

The accounting firm Ernst & Young analyzed the Fiscal Commission’s corporate tax proposal, alongside the one from Senators Wyden and Coats, creating hypothetical companies to illustrate the effects of each plan. (Its report said that there was not yet enough detail in the Ryan plan to include it.) The analysis noted that, “Each plan’s effects on real companies may depend heavily on individual business characteristics such as debt load, capital intensity, and whether the company is profitable. Within any industry there will be winners and losers.”

the individual tax code, we wind up

with a weaker product not a better product.

That said, Ernst & Young found that all four of its hypotheticals-- service companies, tech companies, domestic manufacturers, and multinational manufacturers-- would get a tax cut under the Wyden-Coats plan, with reductions ranging from 2.9 percent for multinationals to nearly 25 percent for domestic service companies. Under the Fiscal Commission proposal, only the hypothetical domestic service company would have its tax bite reduced, a 12.7 percent decline, with small increases for the other three companies.

Both plans would repeal tax-law provisions that allow accelerated depreciation and a deduction for domestic production activities. The Fiscal Commission proposed eliminating the corporate charitable deduction, and the Wyden-Coats plan calls for eliminating deferral of U.S. tax on foreign-source income, proposals that many say won’t pass political muster.

Some say the corporate rate can’t go below 30 percent without other changes--changes that will affect individual taxpayers. “For the rate to go lower, you have to find a way to pay for it,” says KPMG’s Gutman. “The only way to do that is with a broad-based value-added tax … every other industrial country has one.” (A value-added tax is essentially a consumption tax.)

Julia Coronado, an economist at BNP Paribas in New York, agrees. “I don’t know how we ultimately close the fiscal gap without some kind of a value-added tax… It’s certainly the most efficient,” she said in an interview with The Fiscal Times. Still, she notes, “Every time we talk about streamlining the individual tax code, we wind up with a weaker product not a better product.”

Others have suggested increasing tax revenue with a higher rate on capital gains, which was cut to 15 percent in 1997, and eliminating preferential treatment for certain dividends. “Taxing capital gains and dividends as ordinary income (subject to a maximum 28 percent rate on long-term capital gains) would finance a cut in the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to about 26 percent,” Rosanne Altshuler, Benjamin H. Harris and Eric Toder wrote in a paper published by the Tax Policy Center of the Urban Institute and the Brookings Institution.

system instead of requiring companies

to keep two sets of books, one for book

accounting and one for tax accounting."

The paper notes other countries that have lowered their corporate tax rate – including France, Germany, Italy, Norway and Sweden -- have effectively raised the tax individuals pay on dividends. (GOP candidate Pawlenty would eliminate taxes on capital gains, interest income, dividends, and inheritances, according to The Wall Street Journal.)

Others who responded to the TFT survey had a variety of suggestions for what Congress and the administration should do. “We need a unified accounting system, with full disclosure, instead of requiring companies to keep two sets of books, one for book accounting and one for tax accounting, as Congress has required since the 1954 rewrite of the tax code,” said David Cay Johnston, a columnist for Tax Notes and a Pulitzer prize-winning tax reporter who lectures on taxes and regulation at Syracuse University. “In tandem with this, we should study how much we would benefit by exempting legal monopolies from the corporate income tax (while adjusting their authorized return on investment) and imposing instead a visible add-on tax to raise revenue.”

Some focused on job creation. “Tax credits and incentives are well-intentioned but will not drive job creation,” said Jeffrey A. Joerres, CEO of Manpower Inc. “Targeting government funding at new business creation by developing a comprehensive program to support entrepreneurs to set up and establish new businesses is what will spur job growth.”

Richard Trumka, president of the AFL-CIO, said, “The most important reform would be to eliminate tax incentives for corporations to relocate operations and employment overseas… We should also limit the deductibility of interest on corporate debt, which encourages excessive debt and leveraged buyouts that too often harm workers.”

Pavlina R. Tcherneva, an economist at Franklin and Marshal College, also mentioned state taxes. “Any corporate tax reform needs to address two fundamental problems: bidding wars by states to give the most tax breaks for the purpose of relocating existing companies and corporate welfare in the form of massive subsidies that deliver very little job creation,” she said. “A new cardinal measure for corporate subsidies should be instituted that rewards those companies which deliver the maximum number of living-wage jobs per subsidy.”

Eli Dicker, Chief Tax Counsel for the Tax Executives Institute, said the process itself will be complicated. “Congress and the administration need to commit to – and put in place – an open and transparent process to develop the legislation. Taxpayers recognize the road to tax reform will not be easy, simple, or straightforward.”

Tom Herman contributed reporting to this story.

Related Links:

Time to End Wasteful Corporate Tax (Budget & Tax News)

Would Ending Corporate Tax Breaks Make a Dent in the Deficit (Miami Herald)