In his new autobiography, former defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld describes the Pentagon as “an institution that moved with all the speed and dexterity of a half-million-ton oil tanker.”

And that’s when it moved at all.

Rumsfeld is talking about his efforts to get the U.S. military to shed its Cold War legacy systems and become a more agile, more adaptive 21st century fighting force. His main aim, unlike today’s debate about Pentagon budget cuts, isn’t to save money. In fact, he argues the United States could afford to spend more on its military, and during his term from fiscal 2001 to 2006, defense spending rose from $366 billion to $654 billion.

Nonetheless, Rumsfeld’s often frustrating attempts at Defense Department transformation — and the mixed results they produced — serve as an instructive backdrop to the present-day challenges of Pentagon reform. Like Rumsfeld, Pentagon strategists remain concerned with getting the U.S. military more prepared to deal with a world of heightened uncertainty, of small wars as well as possible big ones, of multiple contingencies, and of unconventional threats. This puts a premium on developing more flexible forces and more precise weapons.

Robert Gates, who succeeded Rumsfeld as defense secretary four years ago, has done more than his predecessor to cull troubled programs. He also has put greater emphasis on the need for fiscal constraint, moving to cut overhead costs and reduce personnel and contractor expenses. But the savings Gates has generated have been intended mainly for reinvestment in other, more promising capabilities and programs meant to ensure more effective U.S. forces.

Recruited to Reform the Pentagon

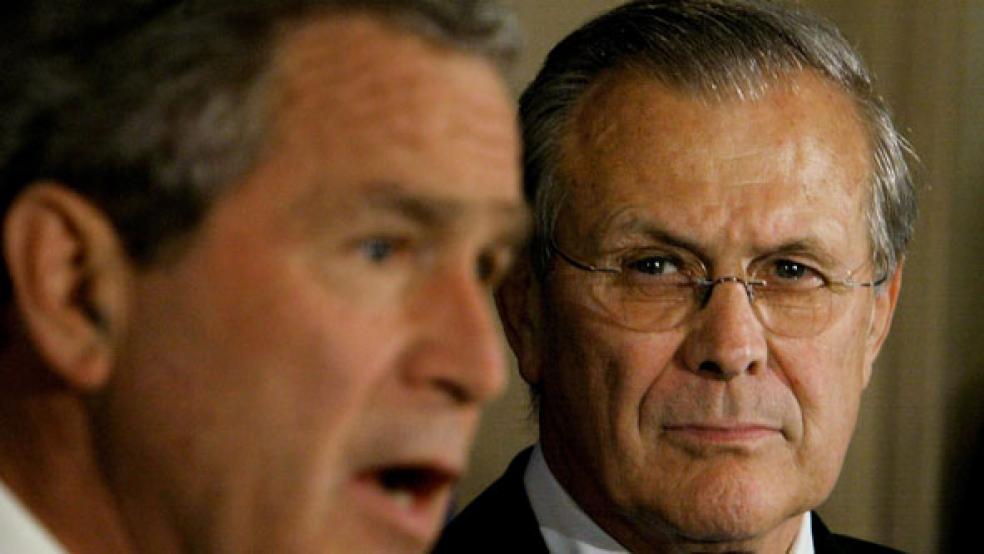

As he notes in his book, Known and Unknown, Rumsfeld was not in the circle of national security experts who in the 1990s advocated for a revolution in U.S. military affairs. He was drafted into the fight. George W. Bush had made the notion of Pentagon transformation a central theme of his 2000 presidential campaign, and after choosing Rumsfeld as defense secretary, instructed him to reshape the armed forces.

Rumsfeld, who had a history of rescuing troubled companies, embraced the mission of changing the Pentagon with much the same hard-charging approach he had shown as a corporate chief executive. Within months of becoming secretary, he managed to alienate many senior officers and a number of key members of Congress, who regarded him as overbearing and inclined to dictate rather than negotiate a new vision for Defense Department programs, weapons and force structure.

An Institution Set in Its Ways

Rumsfeld, in turn, was put off by what he considered deep-seated institutional resistance to change. He writes that he found the “iron triangle” of Congress, the defense contracting industry and the permanent Pentagon bureaucracy “as strong as ever.” Any aggressive effort to alter the status quo, he suggests, was bound to provoke anger and animosity.

He acknowledges that his own tough management style didn’t help. “It was clear that there were some in the department who felt I was brusque or asked more questions than made them comfortable,” he says.

But he cites old-fashioned inertia as the main impediment to his reform efforts. “In a large bureaucratic institution,” he writes, “Newton’s laws of physics apply: A body at rest tends to remain at rest, and a body in motion tends to remain in motion. I was determined that the Department of Defense accelerate forward.”

By the fall of 2001, the betting in Washington was that Rumsfeld would soon be gone, having antagonized too many important people. The 9/11 attacks saved him. His blunt talk and forceful presence suddenly proved very popular with Americans looking to the Pentagon to lead them into the battle against al Qaeda.

Two Wars Take Precedence

The war in Afghanistan, followed by the invasion and prolonged occupation of Iraq, ended up overshadowing Rumsfeld’s transformation campaign. As much as he would have preferred to be remembered most for his efforts at military reform, Rumsfeld himself devotes only about 20 pages of his 800-page memoir to the subject. The bulk of the book, like the bulk of his time as secretary, is consumed by the controversies surrounding his management of the Iraq war, his oversight of detainees in U.S. military custody and his role in the bureaucratic infighting that plagued the Bush administration.

Some of Rumsfeld’s transformation initiatives did have lasting impact. These include the Army’s conversion from cumbersome large divisions to smaller, more deployable brigades, the expansion of special operations forces and the repositioning of U.S. forces abroad.

But others failed to survive after Rumsfeld left office in late 2006. The most notable casualty was the National Security Personnel System, which attempted to provide greater mobility for civilian workers through a new pay-for-performance system. Employees’ unions vigorously opposed the system, and Congress killed it in October 2009.

Rumsfeld denies the widespread view that he came into office with a pet theory favoring high-tech weaponry at the expense of ground forces. But his fiercest battles with the military services involved the Army, and he makes clear in his book that he viewed the Army as “the most resistant to adapting to the new challenges.”

His decision in May 2002 to eliminate the Army’s planned new howitzer, the $11 billion Crusader system, provoked a near-rebellion in the Army establishment and deep hostility in Congress and in the ranks of defense contractors. The move also turned relations between Rumsfeld and the Army’s top leaders — Tom White, the service secretary, and Gen. Eric Shinseki, the Army’s chief of staff — from bad to worse.

Although Rumsfeld contends to this day that the Crusader needed to be cut, he recognizes the beating he took for doing so. “Eventually Congress and the Army supported my decision on the Crusader,” he writes, “but it came at a high cost to me in frayed relationships with a few influential members of Congress and a number in the retired Army community.”

He never tried again to eliminate a major weapons system. (The Army, on its own, later decided to cancel the Comanche reconnaissance helicopter.)

Rumsfeld speaks of transformation less as an end point than a continuing process. The key, he says, has more to do with picking the right people than selecting the best hardware. Indeed, he was more successful in altering Pentagon attitudes and making the military services more receptive to change than he was in achieving actual shifts in weapons programs.

“In my view, transformation hinged more on leadership and organization than it did on technology,” he writes. “Precision-guided weapons and microchips were important, but so was a culture that promoted human innovation and creativity.”