Well before we have any clarity on the impact of the election on health reform, the pundits are handicapping the prospects of efforts to make a serious dent in the national debt and deficit. Three national commissions are hammering out recommendations for reducing the debt and reining in entitlement spending, putting two giant health programs that serve the elderly, disabled and low-income Americans, Medicaid and Medicare, as well as Social Security, in the crosshairs of a new policy debate.

Just yesterday, the Administration's National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, chaired by Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson, released draft recommendations, with final recommendations due before the end of the year. Also yesterday, the Peterson-Pew Commission on Budget Reform issued a report recommending changes in budget process rules to help drive down the national debt. And next week, the Bipartisan Policy Center's Debt Reduction Task Force, chaired by Pete Domenici and Alice Rivlin, is expected to issue their recommendations.

All three groups are tackling very real challenges. The national debt has climbed to $13.7 trillion and the federal deficit has reached nearly $1.4 trillion. Spending on Social Security and mandatory health programs (Medicare, Medicaid and CHIP) account for about 40 percent of the federal budget, and according to CBO, will grow from roughly 10 percent of GDP today to 16 percent in twenty five years, due to the aging of the population and the rising costs of health care. With projections like these few openly support doing nothing, even though how much can actually get through the legislative process remains unclear.

The discussion of these issues is framed almost always in terms of "hard choices" to reduce spending, increase taxes, or both. On the spending side of the ledger, many say the hard choices won't be made because of political realities, including strong resistance from seniors to any changes to Medicare or Social Security. The mid-term election was just the most recent example illustrating the importance of senior voters. In general, Democrats will resist cuts in these programs and Republicans will resist any new taxes.

But these choices are also hard on legitimate policy grounds, especially when it comes to Medicare. And the most important reason they are hard is that so many seniors and disabled people on Medicare have low incomes and already pay a significant share of those incomes for their health care today. It will be difficult if not impossible to ask the majority of beneficiaries ––to pay more or make do with less. That has been the missing element in the entitlement/deficit reduction debate: Warren Buffet is not the typical Medicare beneficiary. Instead the prototype is an older woman with multiple chronic illnesses living on an income of less than $25,000 who spends more than 15 percent of her income on health care. It is the people on these programs and the realities of their lives that have been left out of the discussion.

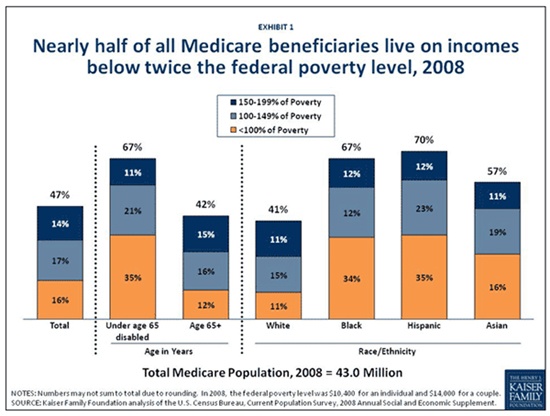

Nearly half (47%) of all elderly and disabled people on Medicare have incomes below twice the federal poverty level (less than $20,800 for an individual and $28,000 for a couple in 2008). Poverty rates are even higher among women, African American and Latino Medicare beneficiaries. And two-thirds of the 8 million disabled people on Medicare who are under age 65 have incomes below twice the poverty rate; beneficiaries with disabilities face more serious access problems than others on the Medicare program.

People on Medicare also already spend a much larger share of their household budgets on health care than the non-elderly do: about 14 percent compared to 4 percent in 2006. And median out-of-pocket health spending for the elderly and disabled on Medicare as a share of income has been rising, from about 12 percent in 1997 to more than 16 percent in 2006 -- with even higher rates for those living below the poverty level (21%) and among those between 100-200 percent of poverty (23%).

Some "hard choices" to be considered may not affect the most vulnerable elderly and disabled, for example proposals that ask higher-income seniors to pay more. The health reform law has already moved further in this direction by increasing the number of higher-income beneficiaries who will pay higher Medicare premiums. Additional efforts to raise costs for higher-income beneficiaries could stir up strong political opposition. Some old ideas may need to be re-evaluated in a post health reform world. For example, proposals to save money by pushing back the retirement age for Medicare to 67 may save money for Medicare, but may not make as significant a dent in federal spending as once envisioned if the 65 and 66 year olds with incomes below 400 percent of poverty become eligible for government tax credits, or for Medicaid, under health reform.

One of the biggest issues likely to emerge is where to draw the line in terms of who should be asked to pay more if policies slow the growth in Medicare by shifting costs to beneficiaries, either directly or indirectly. Who is wealthy enough to pay more? Are adequate protections in place to shield seniors with modest incomes from financial hardship and cost-related access problems? Legislators took one cut at this apple in health reform. The recently enacted health reform law established premium subsidies to limit the financial burden on families with incomes up to 400 percent of the poverty line. The leaders participating in the different debt and deficit reduction commissions and the experts assisting them are certainly aware of these challenges, although they have not really been part of the public discussion to date.

If new policies are proposed to rein in entitlement spending and reduce the deficit, it seems only reasonable to include the following criterion among others for evaluating proposals: do no harm to the financial security or access to care for elderly and disabled beneficiaries living on low and modest incomes. Indeed, given the high out-of-pocket costs these groups have, and the large share of their incomes they already pay for health care, a comprehensive approach might well seek to improve circumstances for these most vulnerable groups, while also advancing "hard choices" for entitlement programs to reduce the deficit.

Drew Altman is president and CEO of the Kaiser Family Foundation.