It was dubbed Washington’s second best address by Harry S. Truman, and it has hosted events for every presidential inaugural since Calvin Coolidge. Franklin Roosevelt used it as a retreat to work on his 1933 inaugural address. And FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover was a lunchtime regular.

The elegant Renaissance Mayflower Hotel, a Washington landmark since 1925, was considered a very hot property when Rockwood Capital of San Francisco acquired it for $260 million in March 2007. Then practically overnight, the real estate market collapsed and credit evaporated in an historic global financial meltdown. The new hotel owners, saddled with $200 million in debt, watched as the value of the property tumbled. By August, it was worth $128 million, according to the credit agency Realpoint.

The Mayflower loan was underwater, the plight of hundreds of billions of dollars worth of commercial properties across the nation that are worth less than their mortgages. A staggering $1.4 trillion of commercial real estate loans will come due nationwide in the next four years, forcing borrowers like Rockwood to find new financing (which they did) or default on their obligations.

This is happening at a time when the capacity to absorb such debt has been slashed, following the bankruptcies of financial firms like Lehman Brothers and the collapse of commercial mortgage-backed securities issuance to a tenth of its peak size. The thought of a string of commercial real estate defaults walloping the barely-recovering economy and jeopardizing the stability of still-tottering banks is enough to keep analysts up at night.

“It’s a very tricky time right now,” said Geoffrey DiMeglio, director of consulting at Market Outlook, a consulting firm. “Even in a weak recovery, I don’t see employment improving the fundamentals in real estate fast enough to get these properties out of default.”

Still, the Washington area is one of the more stable commercial real estate markets in the country thanks to a broad employment base, a sound infrastructure and, of course, a massive government presence. Standard & Poor’s ranks the Washington area as one of the healthiest commercial mortgage-backed securities markets in the country, second only to Massachusetts, largely because of the federal government’s growing demand for office space.

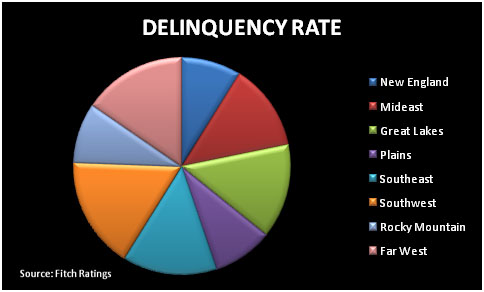

States that suffered the most in the housing bust and manufacturing downturn are at the top of the list for delinquencies: Nevada, Arizona, Michigan, Florida and Ohio, said Larry Kay, a Standard & Poor’s director. But major cities in other states and, to some degree, the regions around them have weathered the storm.

Property owners and lenders may well ride out this storm with lessons from the last major slump in the commercial real estate market. During the collapse of the early 1990s, banks were under pressure to secure a speedy fix for troubled properties. So instead of working with borrowers, they were quicker to process foreclosures and then sell off properties at auction. Lenders ended up losing billions on real estate portfolios they didn’t want to hold and weren’t equipped to manage. The fallout rattled through the economy. In time, the glut of cheap property on the market created a fast and vast run-up in wealth once the market took off again, fueling those heady days of consumer largesse.

it was fast, reasonably fast. This is going to be prolonged.”

Unlike the 1990s, investors in the Mayflower didn’t hit the panic button. Instead they were willing to overlook a missed payment or two and wait out the downturn, absorbing some short-term losses. The wait-and-see attitude of the Mayflower’s creditors signals a shift in thinking. “Right now I think banks are learning that if you give it time, the market can come back and that can lessen the losses that you have to take,” said Douglas J. Donatelli, chairman and chief executive of First Potomac Realty Trust in Bethesda.

While stretching out the payments on a loan may well save it, it could also delay the pain. “Even though it was a bloody situation in the early ’90s, at least it was mercifully quick,” Donatelli said. “A lot of people lost a lot of money and a lot of jobs and a lot of projects changed hands that might not have had to change hands, but it was fast, reasonably fast. This is going to be prolonged.”

Where refinancing doesn’t pan out, cash can save the day. Even Lehman Brothers, still embroiled in bankruptcy proceedings, has managed to scrape together money to save a deal. In 2007, Monday Properties of New York partnered with Lehman to buy 10 Rosslyn office buildings — only to see Lehman go bankrupt 16 months later. This spring, Monday had $239 million of debt coming due on the properties, a situation that seemed ripe for distress. But Lehman secured bankruptcy court approval to join Monday in making an additional $263 million equity investment to erase the debt, said Anthony Westreich, chief executive of Monday Properties.

While “lending and extending” is keeping some properties out of foreclosure, he said, other borrowers are surviving on savings or loans that are still locked into low interest rates. All that could change if interest rates rise, making loan payments pricier, he said, which could push more properties onto the market and create opportunities for buyers.

A large equity stake, Donatelli said, is strong incentive for a borrower to salvage a deal.

“There’s a lot more equity in the real estate market as a whole than there was in the early ’90s,” he said. “Back in the early ’90s there was very little equity. Most projects were built with 100 percent debt. Today it’s really rare to see a project built with 100 percent debt.”

Without question, the stakes are high. Commercial real estate accounts for 6 percent of gross domestic product and property values have fallen more than 40 percent since reaching a high in 2007. The default rate for commercial mortgages held by banks has yet to peak; it hit 4.28 percent in the second quarter and is expected to climb to 5.4 percent by the end of next year. Fitch Rating Service predicts “significant increases in delinquencies on commercial property loans.” Overall, the U.S. economy is balanced between a return to healthy lending and economic growth and continuation of the recession amid anemic capital markets.

“The real flood of these maturing loans hasn’t happened, yet,” said Ben Thypin, senior market analyst at research firm Real Capital Analytics. “If the economy doesn’t get better or gets worse, it’s not very good news.”

lender of their decision with “jingle mail” — sending back the keys.

With banks still reeling from the financial crisis and stingy with their lending, borrowers could fail to find lenders willing to refinance when their mortgages come due. Developers that have the money to pay the debt coming due on an underwater property face the same decision many homeowners have: Is it better to just walk away? In recent months, major commercial-property owners have defaulted on debts and surrendered buildings worth less than their loans.

Companies such as Macerich, Vornado Realty Trust and Simon Property Group stopped making mortgage payments to put pressure on lenders to restructure debts. In some cases they have simply walked away, notifying the lender of their decision with “jingle mail” — sending back the keys. These companies may have piles of cash to make the payments, but a default ultimately pencils out as a better business decision.

Even so, the Mayflower experience offers a ray of hope that despite the “wall” of maturities coming due before 2014, many commercial real estate markets will persevere. After all, a powerful collection of actors have a stake in buoying the sector: investors hunting for bargains, federal regulators who’ve papered over trouble in the past and ultimately, lenders who would rather have some income than amass a collection of non-performing real estate.

“To foreclose or liquidate many of these distressed assets in this market does not make sense,” said Frank A. Innaurato, managing director at Realpoint. “There is a lot of optimism that ... things might be turning around. We’re looking at some point in 2011 where we may hit a turning point, but it’s very much dependant on a willingness to lend.”

Unlike the residential mortgage market collapse, malaise in the commercial real estate sector is more a symptom of a sluggish economy than a looming threat to recovery. When housing prices plummet, household wealth evaporates and consumers cut spending, leading to economic contraction. But trouble in commercial real estate merely reflects the health of the economy, whether slower retail sales, decreased tourism or corporate downsizings. While the sector affects state and local tax revenues and economic growth — thereby touching every taxpayer and resident in the country — it’s unlikely to single-handedly trigger a repeat of the 2008 financial crisis.

Still, interest rates and the overall economy are wild cards. A jump in interest rates would worsen the difficulties borrowers are currently experiencing and increase defaults. Similarly, if the U.S. economy moves into a deflationary cycle, all assets would lose value, including real estate. All these markets are interconnected and their woes ripple through to your bank account, retirement portfolio and level of municipal services you may use.

As Donatelli put it: “There’s an inevitable day of reckoning coming. It might not be as bloody, it might not be as severe, but it’s gonna come, it just might be kicked down the road a couple years.”