After 38 days of suspense, anxiety and frustration, Gulf Coast residents are hoping that BP’s latest attempt to stop the oil leaking from its blown-out Deepwater Horizon well will succeed. But even as reports emerge that the “top kill” may be working, experts are focusing on another aspect of the disaster: its potential impacts on public health.

BP's controversial decision to break down the oil and keep it from reaching the shore by applying massive quantities of toxic chemicals known as dispersants has set off alarms among ecologists and other scientists who think the government and BP have yet to sufficiently address this possible threat.

Those risks have been "substantially underblown," according to Christopher D'Elia, dean of Louisiana State University's School of Coast and Environment. "I'm frankly surprised by the lack of discussion of it at the federal level, or from BP."

The core use of these chemicals has traditionally been viewed as a tradeoff, reducing the amount of oil on the water's surface and the coast, but allowing the oil to remain in the water column, where it can threaten marine life.

CHEMICAL SOUP

But that equation is less applicable to this situation, since BP has poured an unprecedented volume of dispersant – over 800,000 gallons – into the Gulf. This is the first time dispersants have been applied directly at the source of an undersea leak, as opposed to being sprayed onto an oil slick on the water's surface.

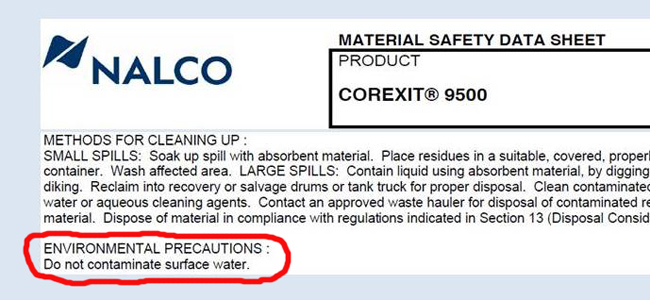

The dispersant COREXIT® 9500 — the chemical BP is using — is considered toxic and could lead to unforeseen health and environmental problems. But it’s at least marginally better than the first dispersant used, COREXIT® EC9527A, which carries warnings that repeated or excessive exposure may cause injury to red blood cells, the kidney or liver.

In 2005, the National Academy of Sciences published a report on dispersants that described current understandings of their effects as "not adequate." Funded by government agencies and oil companies, the report concluded that the risks of "acute and sublethal toxicity from exposure to dispersed oil are not sufficiently understood." The committee of experts who wrote the report recommended a series of coordinated studies to examine those issues. They didn’t happen.

James H. Diaz, a medical toxicologist who heads LSU's environmental and occupational health sciences program, said, “All dispersants have ethylenes in them. And the problem with these toxicants is, for people who are working with them all the time, it can actually de-fat the top layer of the skin, making it dry, and then fissured, and then chapped, and then they can develop a sort of chronic dermatitis. We know a lot about this because painters use similar chemicals to clean their brushes, and people who work in automotive repair use these chemicals to clean your engine and your carburetor. They can effect the peripheral nerves, so a lot people working in automotive repair, after a period of time of touching these products without gloves, or without double-gloves, they lose sensation in their fingertips. That's because the fat insulating the long nerves in the body get dissolved. That's what these things do – they're solvents."

KNOWN UNKNOWNS

"There are still a lot of questions about the potential effects of these dispersants and dispersed oils," said Mark Greeley, an environmental toxicologist at the Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory, who served on the National Academy of Sciences committee. "I wish there had been more progress. I wish we didn't have so many questions to be answered."

On Wednesday, the Coast Guard pulled commercial fishing boats from the cleanup effort in Breton Sound after seven workers reported feeling sick. Four crew members who complained of dizziness, severe headaches and nausea remained hospitalized on Thursday. Meanwhile, scientists aboard a University of South Florida research vessel found a six-mile-wide plume of oil more than two miles beneath the surface, confirming suspicions that much of the oil remains invisible underwater where it will be able to bypass the floating containment booms designed to keep it from reaching land.

Given the uncertainty surrounding dispersants, some critics have accused BP of being less interested in the chemical's effectiveness than in its ability to shape perceptions of the disaster by making it harder to see the oil. "They're trying to dissolve it at the source so we don't see it," said Carl Safina, an ecologist and founder of the Blue Ocean Institute, a conservationist organization in New York. "They're just trying to hide the body, to hide the extent of the problem from view. It's a PR ploy."

David Nicholas, a spokesman for BP, denied that charge. "There's only one reason for putting dispersant onto oil, and that's to prevent surface damage and to break down the oil quicker," he said. But in an implicit acknowledgement of the potential risks, BP has announced that it will donate $500 million over ten years to various institutions, to study the effects of the blowout – including the role of dispersants.

The first recipient of that funding will be LSU. Chris D'Elia, dean of its School of Coast and Environment, intends to use some of the money to gauge the extent to which dispersants increase the risks posed by oil that washes ashore, by preventing toxins in the oil from evaporating.

"Without dispersants, the toxins will evaporate and be taken away by the wind," D'Elia explained. "When you add dispersant, you keep that toxic phase in the water column. Does it ultimately reach the shore? What effect does it have when it gets there? What are the long-term problems to worry about?"

NOW, TO THE WATER

One particular risk might be to the region's water supply, says Diaz. Municipalities throughout southern Louisiana, including New Orleans, draw their water from rivers. Diaz says the complexity of the region's waterways often means water from the Gulf finds its way inland, and not only during a surge resulting from a storm or hurricane. "There comes a point in the summer when water level in the rivers and the bayous are very low, and the Gulf begins to creep up," Diaz said.

If Gulf water is full of dispersed oil that was impossible to skim from the surface, or managed to get below the protective booms lining now lining the coast, toxins could come with it. "If it goes up high enough to get to the freshwater intake of municipal water-treatment systems, that could cause a significant problem," Diaz said.

The Environmental Protection Agency is monitoring air and water in the region for signs of contamination. Chris Ruhl, EPA incident coordinator for field operations in the area, acknowledged that BP's reliance on dispersants added urgency to the monitoring, and described the potential threat to municipal water supplies as a "valid concern."

In the rural fishing communities of southeastern Louisiana, most of the anger about the use of dispersants is directed at BP. The oil has become "an invisible monster," said Billy Nungesser, the president of Plaquemines parish. “Plus, we don't know the health risks.”

On Wednesday night, Nungesser convened a meeting to give locals an opportunity to question Coast Guard and BP officials. A group of oyster farmers at the front of the room waited to hear the latest news, quietly fuming over the many uncertainties they now face, including the impact the dispersants might have on their lives and livelihoods. "Nobody's given us a straight answer," said Matthew Lepetich, an oysterman from Empire. "It's just out of sight, out of mind. The stuff BP puts on the oil is just making it stay deep in the water. It's the only thing they've done well."

Tell us what you think about this story, using the comment box below.