It wasn't supposed to be like this. The economic expansion is in its ninth calendar year. The unemployment rate has plummeted to 4.3 percent, down from more than 8 percent five years ago. Home prices have bounced back. The stock market has never been higher. And the Federal Reserve is in the third year of its monetary policy tightening, confident enough in the pace of economic growth to raise interest rates and hint at the start of a rollback of its bloated $4.4 trillion balance sheet.

And yet, a deepening pullback in the prices of everything from housing to cars and cellphone plans is pushing inflation down sharply.

Related: Modest Rise in US Consumer Prices May Delay Fed Rate Hike

This suggests that perhaps the economy isn't as robust as the Fed and the markets believe — and that the pace of rate hikes could be slowed. More worrisome, it suggests that the economy, already very late in its life cycle based on variety of measures, could be at risk of tipping into a recession if given a push in that direction (like, maybe, an armed confrontation between the United States and North Korea).

The change in trend can be seen in the chart below showing the month-over-month change in producer prices. Last month, prices declined outright for the first time since the summer of 2016.

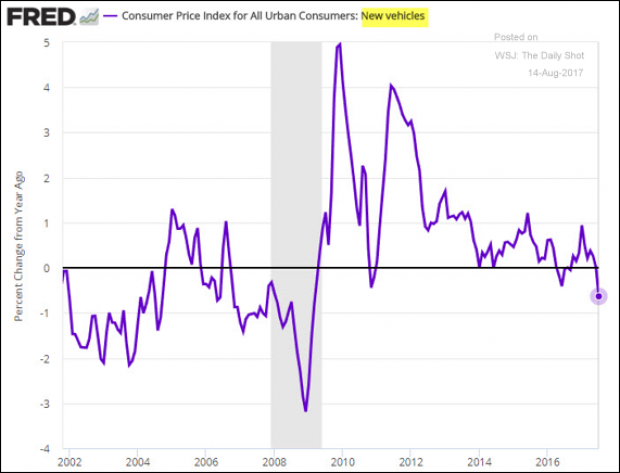

Digging into the specifics, Ed Yardeni of Yardeni Research highlights a few areas where prices have been weak. Physical services inflation fell from a recent year-over-year peak of 4.3 percent last August to -0.6 percent last month. New car prices are basically flat, while used car prices are falling at a 4.1 percent rate.

Fed officials are taking notice. In her last public comment on the issue on July 13, Fed Chair Janet Yellen said it was "premature to conclude the underlying inflation trend is falling well short of 2 percent [the Fed's inflation target]." Yellen stuck to her assumption that higher wages and prices were likely as labor market slack dwindles. She blames price softness on transient factors — like intense price competition by wireless telecoms after Verizon (VZ) relaunched an unlimited data plan — that will prove to be temporary.

Her view isn't shared by all her Fed colleagues.

Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari, in the wake of Friday's tepid Consumer Price Inflation report, admitted that "there is no evidence in any of the data that wages have this acceleration factor and are all of a sudden going to take off." Later that day, Dallas Fed President Robert Kaplan said the Federal Reserve can hold off on raising interest rates until inflation shows clear signs of reaccelerating.

Related: US Economic Expansion to Last Another Two Years or More

Kaplan voted to raise interest rates at the March and June policy meetings. Kashkari dissented at those meetings. Both are unlikely to support another rate hike before the end of the year. Nor are they likely to back a possible start to "quantitative tightening" at the September meeting, the widely expected start of a rolloff of the Fed's $4.4 trillion balance sheet.

But Yellen’s outlook is widely echoed on Wall Street. Societe Generale economist Omair Sharif believes a December rate hike is still in play as the Fed has been trying to downplay the admittedly weak year-over-year inflation rate in favor of stronger sequential gains on a monthly basis. He also highlights the idiosyncrasies in the inflation data, such as the 4.9 percent decline in hotel prices — the largest drop since the data began in 1967.

Yet he has to admit that the disinflation dynamic seems to be spreading: Of the 62 inflation components he tracks, only 22 — or 35 percent — had accelerating year-over-year rates, down from 67 percent back in July.