The big market news over the past week has been the Dow Jones Industrial Average's smooth, consistent, drama-free rise above the 22,000 level. The combination of solid (yet still somewhat tepid) economic data and strong earnings growth (due largely to the rebound in energy prices last year) is proving to be a potent one for stocks.

The dynamics further fueling the gains include hopes that the U.S. dollar's recent downward slide will also boost profitability (particularly for multi-nationals selling overseas) and some recent dovishness from the Federal Reserve (with Chair Janet Yellen admitting interest rates were likely to top out at a low level in this tightening cycle).

But a worrisome characteristic of the uptrend has been its rather narrow focus. Key stocks like Apple (AAPL) and Boeing (BA) have driven the majority of the Dow's upside, while others like General Electric (GE) and IBM (IBM) have been shunned. Boeing in particular has gone vertical in recent weeks, rising 20 percent from its early July level. Given that Boeing is the single largest component in the price-weighted Dow — with a 7.4 percent allocation — it's no surprise the index is performing so well.

Apple has rebounded nearly 10 percent to challenge its May/June highs following a solid earnings report and renewed excitement for the iPhone 8 release. Apple is the Dow's fifth largest component, with a 4.9 percent weighting.

What about GE? Shares are down more than 18 percent from their December high as hopes of a Trump-led surge of pro-growth legislation have fizzled. But as the Dow's smallest component with only a 0.8 percent weighting, the plunge hasn’t stopped the index from reaching new highs.

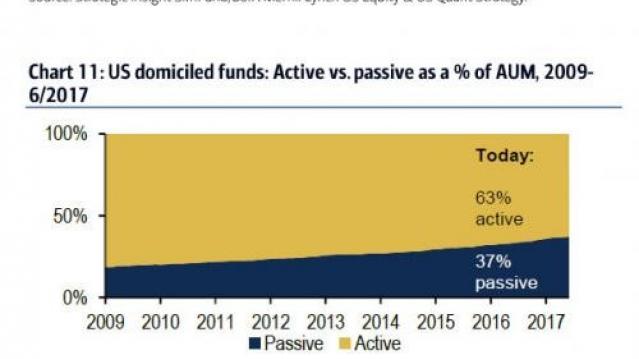

Why should investors care? The financial media is awash with coverage of the rise of passive, index-based investing. The investing strategy popularized by Vanguard's John Bogle in 1975 has outperformed active strategies and hot-shot hedge fund managers in recent years. According to Oaktree Capital's Howard Marks, about 20 percent of equity mutual fund assets in 2014 were in passive strategies; now, it's more like 37 percent.

Over the past 10 years, $1.4 trillion has flowed into passive funds and ETFs while $1.2 trillion has flowed out of actively managed funds. The sea change has been motivated by the environment, created by central banks, of ultra-low interest rates and massive asset purchase programs, creating a situation where volatility is crushed and various asset classes move as one.

Moreover, things like lower expenses and the inability, by definition, to underperform the associated index/benchmark are seen as permanent, structural advantages to passive funds vs. active ones.

The trouble is: Passive investing, at least in the major index funds, is basically momentum investing writ large.

The better those passive funds do, the more money they attract, which further increases their performance because the money — with only rare exception — isn't evenly distributed amongst all the index components. Funds that invest in both market-cap indexes like the S&P 500 and price-weighted indexes like the Dow steadily increase their exposure to hot stocks. As Apple's share price rises, it's weighting in the Dow grows. As its share price rises, its market capitalization rises, increasing its S&P 500 allocation.

This works wonders when things are going well. But it sows the seeds of trouble since this increasing allocation reduces diversification. Put differently, people investing in the Dow — perhaps without realizing it — are steadily increasing their exposure to Boeing.

When an eventual market decline does materialize, the concentration of capital in passive strategies could worsen the pullback. Active managers are more likely to "supply volume" during panics since those with a value mandate are searching for downtrodden turnaround plays with long-term promise. Yet passive strategies dedicate allocations purely on price. Should Apple's share price fall 50 percent, for the sake of argument, passive fund will be persistently selling into the decline — known as "demanding volume" and thus possibly amplifying the selloff.

Jason Goepfert at SentimenTrader notes that this trend is taking place as investors’ cash levels have fallen to lows last seen in February 2000, while common indicators of market valuation and complacency are at extremes last seen in 1993. In that case, what followed was a near-10 percent selloff in 1994 before the dot-com bubble began in earnest.

Anthony Mirhaydari is founder of the Edge (ETFs) and Edge Pro (Options) investment advisory newsletters. A two-week and four-week free trial offer has been extended to Fiscal Times readers. Redeem by clicking the links above.