With the Commerce Department’s Friday announcement of low second-quarter growth, Americans are left wondering what the Fed has been up to—and what it will do when the United States falls into a recession.

The second quarter growth rate came in at 1.2 percent on an annualized basis, well below economists’ forecasts of 2.5 percent growth. In addition, the first quarter GDP was revised down from 1.1 percent to 0.8 percent. The rate of GDP growth is 1 percent for 2016 and 1.2 percent over the past four quarters. This slowing growth does not bode well for anyone.

The data were a surprise to markets and forecasters: Unlike the employment numbers from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which provide the first flash of data from the previous month, economists have a substantial collection of data to forecast quarterly GDP growth. By the time the first estimate comes out, different government departments have published estimates of two or three months of employment, retail sales, factory orders, and a host of other data points to guide the forecast.

Related: Atlanta Fed slashes U.S. second quarter GDP growth view to 1.8 percent

The problem was not consumers, who went shopping at the healthiest rate since the fourth quarter of 2014, resulting in an increase in personal consumption expenditures of over 4 percent. The problem was declining domestic investment across the board.

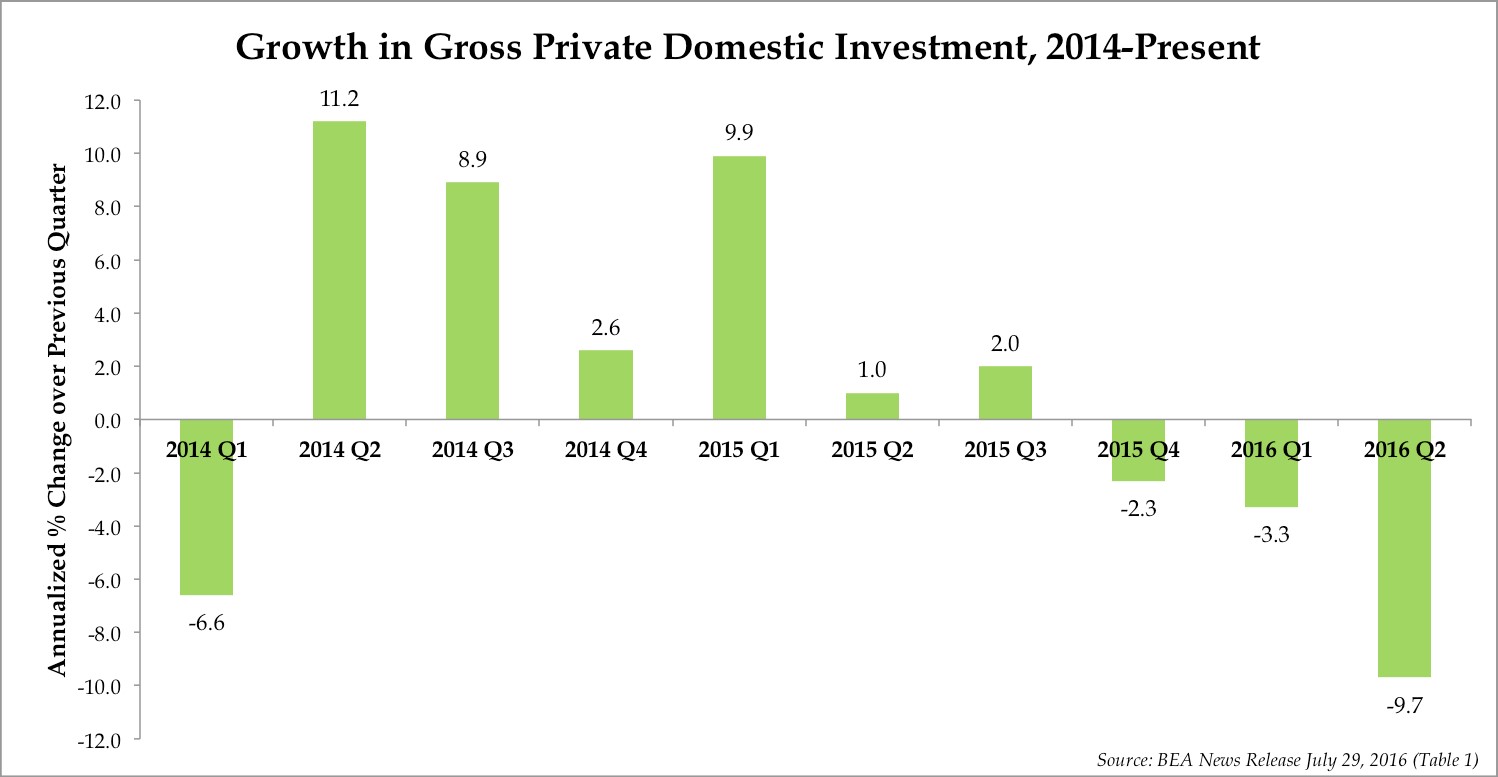

Consider that gross private domestic investment declined by 9.7 percent on an annualized basis from the first quarter of 2016 to the second quarter. Over the past year, it declined by 3.4 percent.

Within the category of domestic investment, second quarter nonresidential structure investments declined by 7.9 percent on an annualized basis relative to the first quarter, and nonresidential equipment by 3.5 percent. Residential investment was lower by 6.1 percent.

American individuals and businesses were reluctant to make investments in the second quarter. The declining investments are all the more remarkable given the Fed’s abnormally-low interest rates. The Fed has now held interest rates historically low for several years. If low interest rates cannot increase investment, then what can?

Related: U.S. Says Probe Found Problem in Seasonal Adjustment of GDP Data

The new GDP figures show the increased importance of ideas included in the House Republican tax plan, released in June. It would stimulate investment by allowing the cost of capital investment to be written off in the first year, instead of being amortized over time. All business taxes would be border-adjustable, so there would be no tax on foreign-derived profits and exports, and no deduction for purchases from abroad.

This means that if a company were to buy an input from abroad to use in its production process in the United States, it would not be able to deduct the cost of that input. On the other hand, if it exported products, it would not be taxed on their sale. This encourages production within the United States, increasing investment and jobs.

This form of corporate taxation, known as a destination-based cash flow-tax, has been proposed by University of California professor Alan Auerbach, University of Oxford professor Michael Devereux, and University of Bristol professor Helen Simpson. The advantages are that it does not tax additions to investment; it encourages investment in the United States rather than abroad; and it does not allow a deduction for interest, so it gets rid of the benefit of debt.

Related: Traders Pare U.S. Rate-Hike View on Weak GDP Data

The House Republican plan also proposes smarter regulation. The onslaught of new regulations is discouraging companies from making investments. Some regulations, such as the EPA’s Clean Power Plan and the Labor Department’s persuader rule, have been held up by the courts. Others are moving inexorably forward, resulting in potential lower profits and increased uncertainty.

The second quarter GDP numbers are proof that the Fed alone cannot drive the economy. The low interest rates might have been effective at the start of the recession, but are no longer effective now. The Fed should raise them in September, and continue by raising them at every Fed meeting until interest rates approach historical norms. Incentives other than low interest rates can stimulate investment. To understand how, just ask the House Republicans.

This article was originally published in Economics21 a website of the Manhattan Institute.