Suddenly, the unthinkable has become likely: For the first time, the futures market is putting the odds of a Federal Reserve interest rate hike in December at 50 percent. It's even money that the cost of credit will rise — for the first time since 2006 — just before Christmas.

Expectations shifted after language was removed from the Fed's policy statement about near-term pressures on inflation, while a line was added about how economic data was being monitored to determine whether it will be appropriate to raise interest rates "at its next meeting."

But instead of giving clarity and confidence to market participants, the statement has only sown more uncertainty and confusion.

It's all become a bit surreal — the way the market follows every hint, wink, hushed whisper and economic data point as if life itself depended on it, all in the pursuit of a clue that would tilt odds of a December one way or another. Untold billions depend on making the right choice.

Related: Why the Stock Market Is Partying Like It’s 1999

Stanford economist John B. Taylor, creator of the "Taylor Rule" that tries to take voodoo of discretionary monetary policy out of the hands of Fed policymakers and replace it with an ordered, transparent and data-dependent approach — recently clashed with New York Fed President Bill Dudley at a Brookings Institution forum dubbed "The Fed at a crossroads: Where to go next?"

Dudley feigned surprise that everyone is so confused, reiterating the Fed's focus on GDP growth and pressure on the labor market. Taylor ripped in: "Are you kidding? No one knows what you're doing." Laughter followed, because he hit a nerve: For years, the Fed has moved the goalposts on when policy normalization was going to happen seemingly without reason.

Unemployment rate thresholds, such as the 6.5 percent rate of 2012, have come and gone. Key words like "patient" and phrases like "considerable time" have come and gone to great fanfare. Now, we are left with this:

"The Committee anticipates that it will be appropriate to raise the target range for the federal funds rate when it has seen some further improvement in the labor market and is reasonably confident that inflation will move back to its 2 percent objective over the medium term."

To this one must add, based on the Fed's comments, financial market stability (read: stock prices) and global economic and financial developments (read: China).

Related: How Rising Rents Are About to Crush American Spending Power

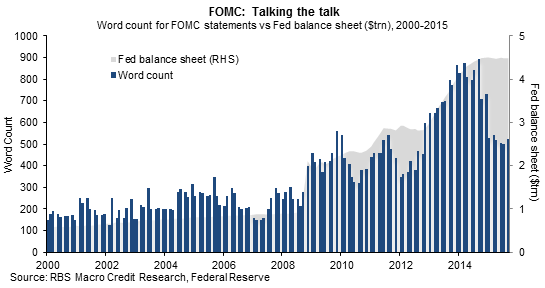

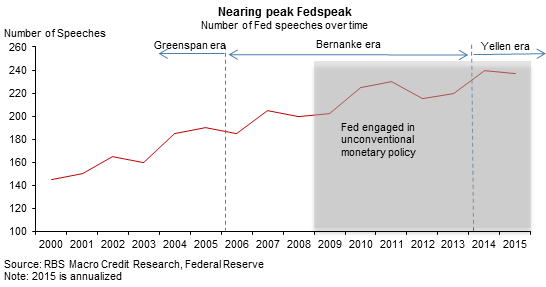

Alberto Gallo, head of macro credit research at RBS, illustrated the growing scale of this policymaking circus by showing in a recent note to clients how the word count of the Fed's policy statements as well as the number of speeches by Fed officials have been surging over the past decade, presumably as policymakers have felt the need to explain and discuss the unconventional measures they’ve taken or considered.

A study of market responses to so-called "hawkish" signals — Fed comments or economic data suggesting a rate hike had moved closer — shows they are becoming less and less potent. Gallo believes the market has caught onto the Fed's dovish bias, as the Fed itself becomes more sensitive to markets in its policy setting. It's become a self-reinforcing and increasingly dangerous dynamic.

Just look at the violent reaction in the stock market to last Wednesday's Fed announcement: The Dow Jones Industrial Average churned in a 220-point range over just two hours.

Related: Why We Might Be Headed for a Recession in 2016

This paradox was explained by former Fed Governor Jeremy Stein before he left office:

"There is always a temptation for the central bank to speak in a whisper, because anything that gets said reverberates so loudly in markets. But the softer it talks, the more the market leans in to hear better and, thus, the more the whisper gets amplified. So efforts to overly manage the market volatility associated with our communications may ultimately be self-defeating."

Societe Generale economist Aneta Markowska has bumped up her odds of a December hike to 45 percent, from 40 percent before. She notes that in its policy statement on Wednesday, the Fed softened its language on the labor market ("the pace of job gains slowed") but buffed up its language on domestic demand, despite disappointing retail sales and durable goods reports recently. More mixed signals.

The flow of economic data and the takeaway from Fed speeches will only increase in importance now, making the hike/no hike guessing game even more unbearable. Capital Economics' Chief North American Economist Paul Ashworth still believes that the November and December payroll reports won't be strong enough to justify rate liftoff this year, pushing policy normalization into 2016.

Related: These Simple Steps Could Prevent Another Financial Crisis

Michael Feroli, chief U.S. economist at J.P. Morgan, notes that the Fed's statement included the first explicit mention of possible action at its next policy meeting since 1999. In his words, "it's hard to see how the statement could have been more direct in flagging the risk of a December hike." That sounds scary on the surface but would be undermined by weak economic data. Again, more uncertainty.

Gallo doesn't believe the Fed can hike this year — despite its own forward guidance suggesting it should — because of low inflation, upward pressure on the dollar from easing or the threat of easing from the European Central Bank and the People's Bank of China, and end-of-year trading liquidity concerns (especially in high-yield bonds) that could exacerbate any negative market reaction to a December rate hike.

Each sounds like a plausible result since, at this point, one guess is as good as any other.