We are now just hours away from the most important Federal Reserve policy decision in a generation —one that could result in the first interest rate hike in nine years and begin unwinding the greatest experiment in cheap money policy in human history. There is no easy choice for Fed Chair Janet Yellen in the most pivotal moment of her career.

It's not hyperbole: This bull market has been sustained by the Fed's stimulus while an emerging market credit binge has been financed with cheap dollars. Stocks moved higher on Monday and Tuesday as optimism builds the Fed will once again give the market what it wants and wait, possibly until 2016, before ending its near-zero percent interest rate policy that's been in place since 2008. Futures market odds put a rate hike now at less than 30 percent.

"No hike" hopes have been bolstered by a batch of disappointing economic data this week on retail sales, industrial production and consumer price inflation. That's lifted equities, bounced precious metals and pushed up bond-market inflation expectations in a way not seen since April.

And yet there is a nagging fear the Fed could deliver a hawkish surprise given cumulative progress on job gains and economic growth.

Related: Forget China, the More Immediate Threat to Your Portfolio Is From Congress

A survey of 135 institutional investors by Alberto Gallo, the head of macro credit research at Royal Bank of Scotland, revealed the depth of the cognitive dissonance in play.

A majority believes the Fed should hike now, with 63 percent saying central bankers are losing credibility with their repeated kowtowing to markets. Gallo adds that it's becoming increasingly clear that extreme monetary policy is becoming less effective the longer it goes on, while, worryingly, making an eventual exit increasingly difficult. Eighty percent of those surveyed believe the Fed should hike by the end of the year.

Yet according to Gallo, only 42 percent of respondents believe the Fed will hike now. The International Monetary Fund, Chinese policymakers, Goldman Sachs and Larry Summers are among those warning the Fed that a hike now would be premature. Central banks that have attempted to raise interest rates since the financial crisis, such as those in Israel and Chile, have all had to backtrack and cut rates to various degrees.

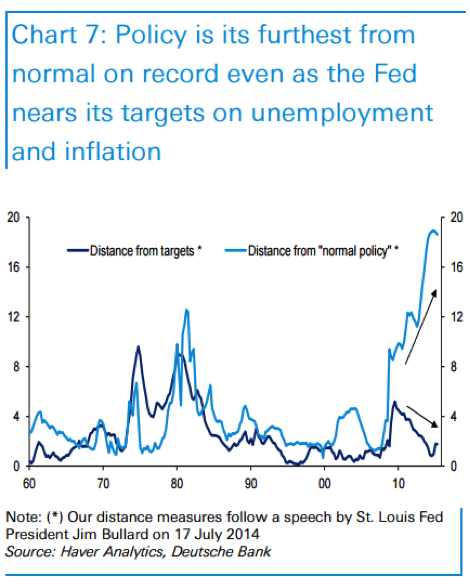

Yet others, such as the Bank for International Settlements and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, say that now's the time to pull the monetary punchbowl away. Deutsche Bank, in the chart above, shows how monetary policy remains in emergency mode despite the Fed nearing its mandate targets on inflation and employment.

Remember, all of this is the result of efforts to end the financial crisis that resulted from the bursting of the housing bubble and the mortgage-backed securities that funded it — a speculative fever caused by the Fed keeping interest rates too low during the mid-2000s. The Fed's juicing of stock and bond prices was justified by the positive "wealth effect" that resulted. In 2010, after unleashing the $600 billion "QE2" bond purchase program, former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke wrote in The Washington Post that the action was done in part to lift stock prices to "boost consumer wealth and help increase confidence, which can also spur spending."

Related: Seven Reasons the Fed Won’t Hike Interest Rates

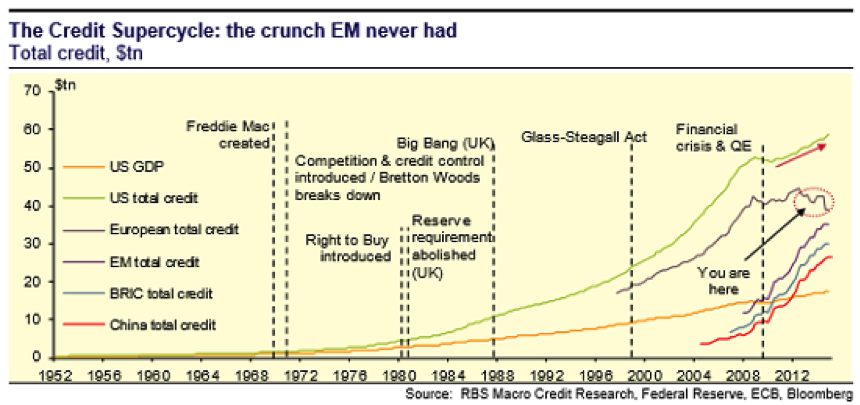

But there are risks to the easy money policy that’s been in place for so long. As Gallo notes, “investors are concerned with structural imbalances building up further if ultra-loose monetary policy continues."

Specifically, the realists on Wall Street are focused on the very scary rise in dollar-denominated debt in the emerging market economies. Also, the growing magnitude of each successive credit boom and bust cycle as the Fed has gotten more and more aggressive over the past decades is a concern. As is the low-volatility fragility in many areas of the bond market caused by regulatory changes, central bank purchases and investor herding. "If the Fed's mandate is to worry about the medium-term and to target structural issues, the right thing to do would be to hike,” Gallo says. “This is also what the majority of institutional investors think."

The IMF recently warned that correlations among major asset classes and between fund positions have risen in a big way since the financial crisis — setting the stage for more seismic shake-ups once the Fed finally hikes, as everyone rushes for the exit amid low liquidity and diminished diversification protection.

Yet the most likely response, as revealed in the survey data, in futures pricing and in market action this week, is another policy punt. Morgan Stanley's Guneet Dhingra notes that in the 1999 and 2004 rate hike cycles, the Fed only moved when the market was fully prepared. In the 2004 campaign, no hikes occurred unless futures odds were 79 percent or higher the day before the decision.

Our central bank simply isn't in the business of delivering hawkish surprises to the stock market. And institutional investors know this. Yet this only raises the stakes for the next "will they or won't they" rate decision in October.