It’s the latest episode of global survivor, only this time, it’s not a tsunami, an earthquake, or even a war that has torn through a country and ravaged its people.

Eleven million Greek citizens are struggling to cope without a banking system, without credit cards, with cash-only creditors who supply everything from insulin for diabetics to food. Luckily, the European pharma companies have agreed to continue supplying medicine for another month, even though they’re owed over $1.2 billion and haven’t been paid since last December.

People are in survival mode—hoarding food and supplies, filling gas cans and the like. But true to character, they’re still drinking $5 a day cups of java. All this in anticipation of a new deal from Europe that may never come.

Related: Greece’s New Marxist Finance Minister: More Polished, More Radical?

On Sunday, in a crucial referendum, Greek voters gave a resounding “no” to a bailout from European creditors that would have forced the country’s leaders to impose additional austerity measures, hurting some of the most vulnerable citizens in exchange.

That doesn’t get Greece and its Prime Minister, Alexis Tsipras off the hook.

It’s true that the financial crisis exacerbated Greece’s existing high level of debt, as it did every other developed country. Yet unlike most others, Greece never recovered, as debt piled on and the country’s debt to GDP ratio hit an unsustainable 177 percent.

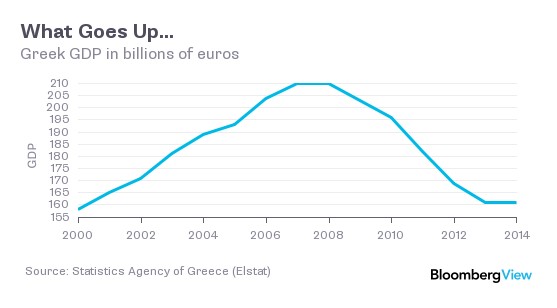

Two analysts from Bloomberg, Konstantine Gatsios and Dimitrios A. Ioannou, argue that the Greek economy was failing before and after the housing bubble burst—a bubble that falsely pumped up expectations – and pension payouts. They claim that additional stimulus would not have spurred Greece’s economy because consumer purchasing was never strong enough to reduce the country’s debt in the first place.

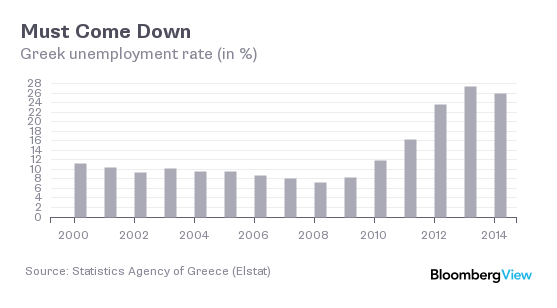

“Greece's gross domestic product was similar in 2001 and 2014, measured in constant 2005 prices, meaning that ‘effective demand’ in these two years before and after the debt crisis was approximately equal. And yet unemployment in 2014 was almost triple the 2001 level. The key to resolving Greece's economic woes must, therefore, lie in something other than demand,” Gatsios and Ioannou wrote.

Related: Greece: What You Need to Know After the “No” Vote

Gatsios and Ioannou point out that Greek imports exceeded exports by almost 60 percent. They describe a different problem—the lack of a viable home grown economy of goods and services.

Greece’s moribund economy isn’t the only challenge facing that country. For years, apparently, the government had been cooking the books, borrowing more than they were reporting publicly. The EU member rule on deficits is 3 percent of GDP (Greece’s was actually 12.7percent), and the EU debt limit is a somewhat flexible 60 percent of GDP.

No way could Greece meet those mandates, unless they decided to get real about collecting taxes. About a third of Greeks are self-employed, the highest rate in the EU. But according to Vox, “The true income of the average Greek person is about 92 percent higher than the income they report to the government.”

Where does all this leave Greece and the Eurozone?

Related: Inside the Failed Greek Debt Negotiations

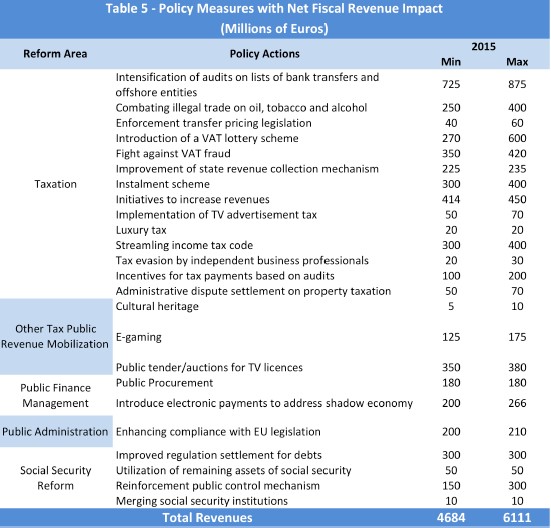

For starters, there’s a growing disconnect between the players. Alexis Tsipras believes his country’s definitive “no” vote against further austerity means the EU will cave on at least some of Greece’s massive debt and focus on the reforms his government presented in March, 2015.

But German Chancellor Angela Merkel and other European leaders have heard it all before from one of Tsipras’s predecessors, George Papandreou—promises on debt reform that were never kept. They don’t believe that Greece has the proper infrastructure to implement the reforms they are promising, including collecting taxes. As a result, Merkel declared the ball is now in Greece’s court.

The EU is unlikely to forgive Greece’s debt and set such a precedent with economic problems in Italy, Spain and Portugal still lurking on the horizon. Interestingly, Spain's Economy Minister Luis de Guindos, who had been adamantly against a third bailout for Greece back in March, softened his position when EU negotiators thought they could still strike a deal with Tsipras on debt reform. But that was then.

Meanwhile, embattled Greek finance Minister, Yanis Varoufakis resigned today and was replaced by Oxford-educated Euclid Tsakalotos, a Marxist economist. Tsakalotos could be the period at the end of a passage of a very long Greek drama—especially if he decides that Russia or even China are a better fit for Greece than Europe.

Related: The Political Failures Behind the Greek Debt Crisis

So what’s next? Tsipras believes Greek voters changed the game when they voted “no” on the referendum. What he may be forgetting is that Germans and other Europeans vote, too. And they don’t like being pushed against the wall.

Assuming the two sides continue to talk, or even kick the can down the road, the economic crisis in Greece is so dire – and likely to continue – that it is fast becoming a serious humanitarian crisis that will indeed need a bailout of sorts. Food, clothing, medicine—it’s all on the line for a country whose forefathers drafted the blueprints for modern societies.

Greece gave us democracy, the social contract, and the great philosophers, including Plutarch. Plutarch is important because he gave us the 7 key points of learning in Moralia. One of them seems to have eluded the current administration: “Learn about the past in order to thrive in the future.”

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: