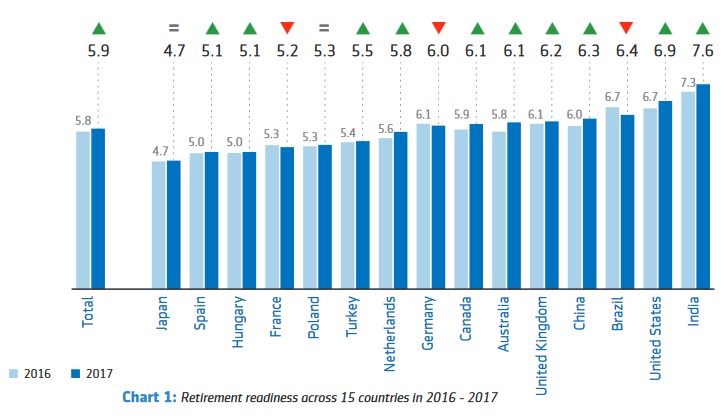

The 6th annual Aegon Retirement Readiness Survey, released this week by the Aegon Center for Longevity and Retirement, includes an important finding: For the first time, over half of the countries surveyed achieved a 6.0 or better on a 10-point measure of “readiness for retirement.” (Scores of 6 to 7.9 are considered “medium,” while scores above that are considered “high” for retirement readiness.)

The overall average readiness score in the 15 countries surveyed -- Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, Hungary, India, Japan, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Turkey, the U.K. and the U.S. – was 5.92, a slight improvement over 2016. Aegon has surveyed over 86,000 workers and retirees since 2012, so the data set for measuring the level of readiness is pretty solid.

Related: 15 Great Jobs for Retirees

At the same time, 57 percent of those surveyed envision that they will continue working in some form into retirement.

For governments facing the misalignment between the 20th century models of retirement – where work ends abruptly and fully at 65 or younger -- the Aegon report can inform health, pension and savings reforms.

For individuals, the survey underscores the importance of a comprehensive, concrete longevity plan that includes health, wellness and financial planning elements. Such a plan can make a life-changing difference: 74 percent of those with a written retirement plan are always saving for retirement, versus just 19 percent of those with no plan. And in addition to saving, individuals must also plan for flexible work arrangements and extended employment, including by accepting their part of the bargain on issues like pay and promotion.

For employers, the results identify the growing talent pool of older workers, the majority of whom expect to continue past traditional 20th century retirement age. Tapping this immense talent resource will require flexible work arrangements, such as part-time work, on-demand jobs and tele-commuting, as well as programs to support the increasing number of employees caring for older relatives. This also means helping workers maintain their own health so they can stay in the workforce; 91 percent of those surveyed say they would be interested in health- and wellness-related offerings from their employer.

For governments, the survey highlights the urgency of designing programs that help individuals navigate the new retirement landscape. These include awareness campaigns focused on planning and saving for retirement, incentives for “phased retirement” and longer working lives, and working with employers to articulate the ROI of recruiting, hiring and retaining older workers. Forward-looking governments – Norway recently adjusted its national retirement age to range all the way up to the mid-70s, and Singapore now gives employers incentives to hire back older workers -- will seek out and assess a variety of programs from around the world. All this is opening a new period of global policy innovation for today’s challenges and opportunities related to later-life work, saving and health.

Related: What You Don’t Know About Medicare Could Hurt Your Retirement

For the World Health Organization, the findings show how the promotion of health and wellness can and must be integrated into wellness strategies where the metric is functional ability. According to the survey, 29 percent of those who retire sooner than planned are forced to do so because of ill health. Indeed, financial and physical wellness are inextricably linked, and together they require joint strategies to help older adults maintain their functional ability and work as long as they want, which also provides the resources necessary to pay for medical needs. The survey’s results should help to guide the implementation of the WHO’s ageing and health strategy, recognizing and leveraging these connections.

From a broader perspective, the survey reveals the need for a wholesale cultural shift to support later-life work. The retirement models and assumptions of mid-20th century are not effective for today’s needs. Individuals are already realizing this and planning for our new 21st century reality; we now need employers, governments and global institutions to catch up. This means promoting perceptions of older workers as contributors, leaders, entrepreneurs and prized talent, and then translating this shifted culture into new policies and strategies.

Workers no longer expect or want their careers to end at 60 or 65. Our solutions can’t end then, either.