We're now deep in the third-quarter earnings season. And, as is typical, positive surprises have outweighed negative ones. Witness Microsoft (MSFT) or the big Wall Street banks. With stock prices stable and headlines positive, one could easily forget we're in the midst of a corporate earnings recession expected to stretch into its fifth consecutive quarter.

According to FactSet, as of Friday, with 23 percent of S&P 500 earnings in the bag, 78 percent have reported better-than-expected earnings. Overall earnings are still expected to drop 0.3 percent.

Related: 7 Big Risks That Could Derail the Stock Market’s Rally

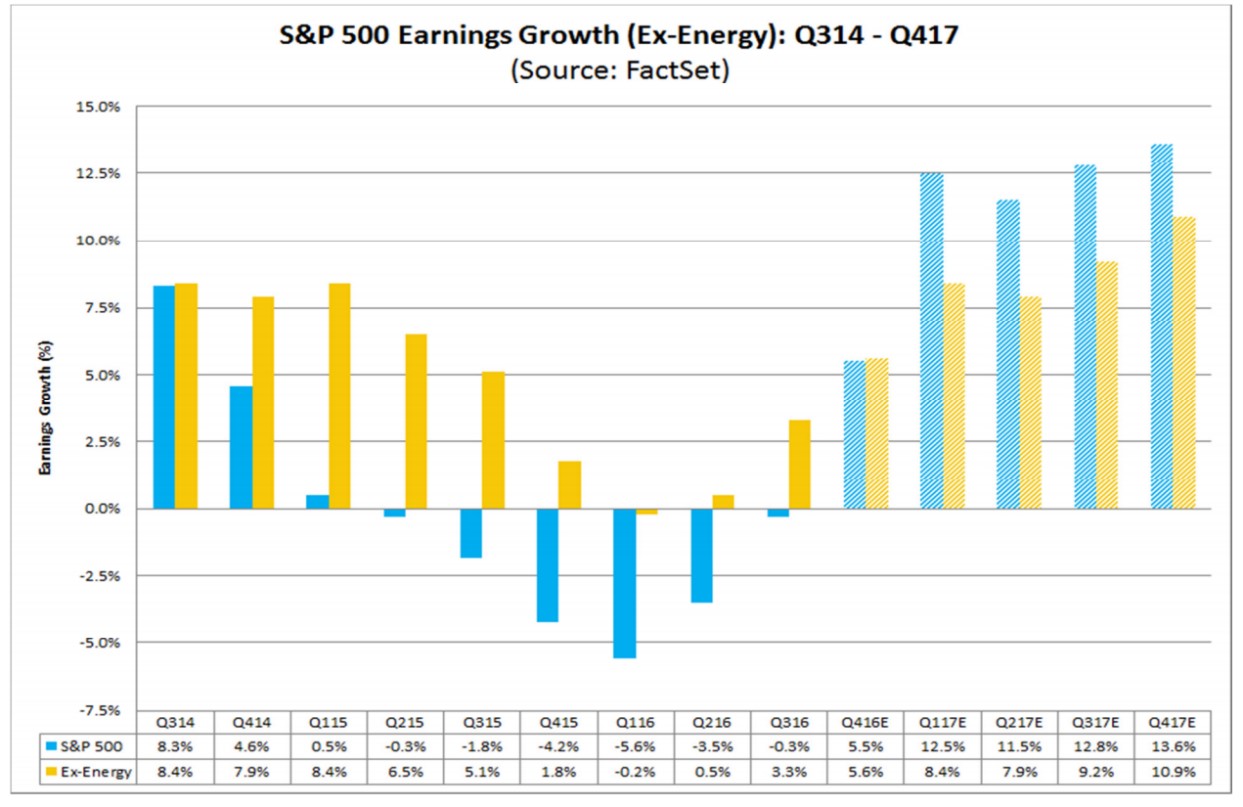

Yet hope springs eternal. With energy prices on the mend and pushing into positive territory year-over-year, the drag from the likes of Exxon Mobil (XOM) and Chevron (CVX) is soon expected to fade and thus analysts are looking for earnings growth to dramatically return by the end of the year.

But is this hope overly optimistic? I think so.

Take a look at the earnings expectations in the chart above. A lot has to go right for the optimism illustrated here to come to fruition. The U.S. presidential election needs to go smoothly. The Federal Reserve's determination to raise interest rates in December either needs to fade or Wall Street needs to get happier about the prospect of higher interest rates. Economic data in China and Europe need to get better.

Related: How Higher Wages Could Sink the Economy

Most importantly, U.S. GDP growth needs to accelerate from its current moribund pace. Things are zombie-like right now: The Atlanta Fed's GDPNow estimate for the third quarter is at just 2.0 percent, down from a high of 3.8 percent in August. This follows growth of 1.4 percent in Q2 and just 1.1 percent in Q1.

I'm just going say it: The economic expansion looks like it's dying. And that's simply not conducive to the epic profitability rebound Wall Street is touting to its clients.

Wall Street economists, separate from the equity analysts, are decidedly downcast by comparison. Deutsche Bank's chief U.S. economist, Joseph LaVorgna, who earned a reputation as something of a perennial optimist, challenged that stereotype with a warning that the evidence is mounting the business cycle has entered its terminal phase.

Related: The Election Matters for the Future of the Economy

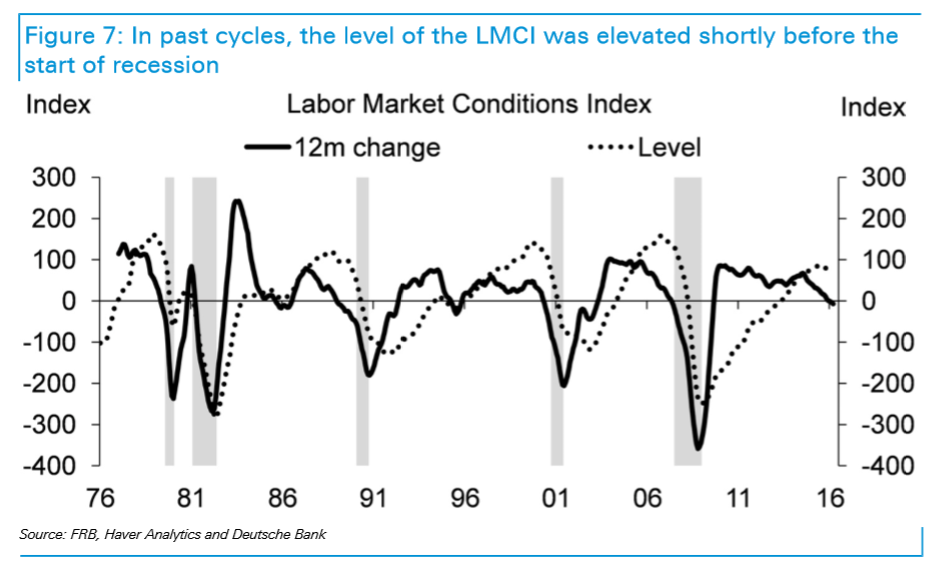

For one thing, the labor market is showing the hallmarks of tightness that historically fuels wage gains and broader inflation, forcing the Fed to tighten monetary policy. LaVorgna notes that the Fed's own Labor Conditions Index (LMCI) dropped 2.2 points in September — the eighth decline in the last nine months. In July, the year-over-year change in the LMCI turned negative for only the eighth time in the last 40 years.

Five of the previous seven annual declines in this measure were associated with recessions. In other words, if that history is a guide, there is less than a one-in-three chance this is a false alarm.

Related: US Economy Shows Hints of Broadening Wage Pressures, Fed Says

On its face, this seems at odds with jobless claims falling to levels not seen since the 1970s or an unemployment rate at 5 percent or the relatively stable rise in payrolls we've seen this year. But other, more forward-looking measures of the labor market that go into the LMCI (comprised of 19 indicators in total) are flashing warning signals.

Since labor is one of the largest expense items for a company, early indications of a pullback in hiring suggest executives are battening down in response to a decline in labor productivity (new workers aren't as qualified/good and aren't as efficient) as unit labor costs start drifting higher (nascent wage inflation).

All of this pinches profit margins, which are already pressured by higher aggregate debt levels (the result of all those bond-funded equity buyback programs) and the fact S&P 500 companies haven't seen top-line sales growth since 2014.

Related: Global Debt Hits a Record $152 Trillion. Is That as Scary as It Sounds?

What then of the argument that energy-sector earnings are about to surge thanks to the OPEC-driven recovery in oil prices? West Texas Intermediate crossed over the $52-a-barrel threshold this month for the first time since the summer of 2015.

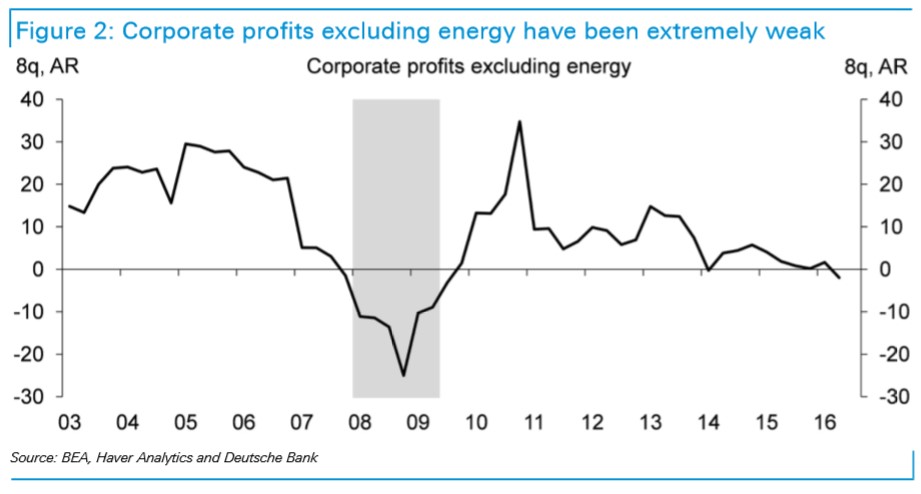

Setting aside the discussion of whether OPEC nations and possibly Russia will actually agree to cut output, the chart above shows that the earnings decline cannot simply be blamed on the energy sector. Deeper problems are in play that have pulled ex-energy corporate profits down 6.1 percent from their peak in 2014.

Related: Oil Prices Are Creating a Goldilocks Scenario for the Global Economy

Unless what's ailing the non-energy economy changes soon — including the strong U.S. dollar, weak consumer spending, weak overseas growth, higher labor costs, etc. — the earnings bounce simply isn't going to happen as the recession warnings from the labor market grow louder.