The concept of free trade is plumbing new depths in popularity this election season. Never a winner with liberal Democrats, the idea is also losing support among Republicans as Trump-style populism supplants the party’s free-market fundamentalism. This is too bad because free trade has done much to raise billions of people out of poverty, and it can benefit the world — including the U.S. — much more if properly understood and implemented.

One reason the U.S. has been so successful as a nation is that we are a massive free-trade zone. Back in the 1780s, states actually imposed tariffs and trade restrictions on one another. A great benefit of the Constitution is that it swept away barriers to interstate trade, and now allows all 300 million of us to freely transact with one another.

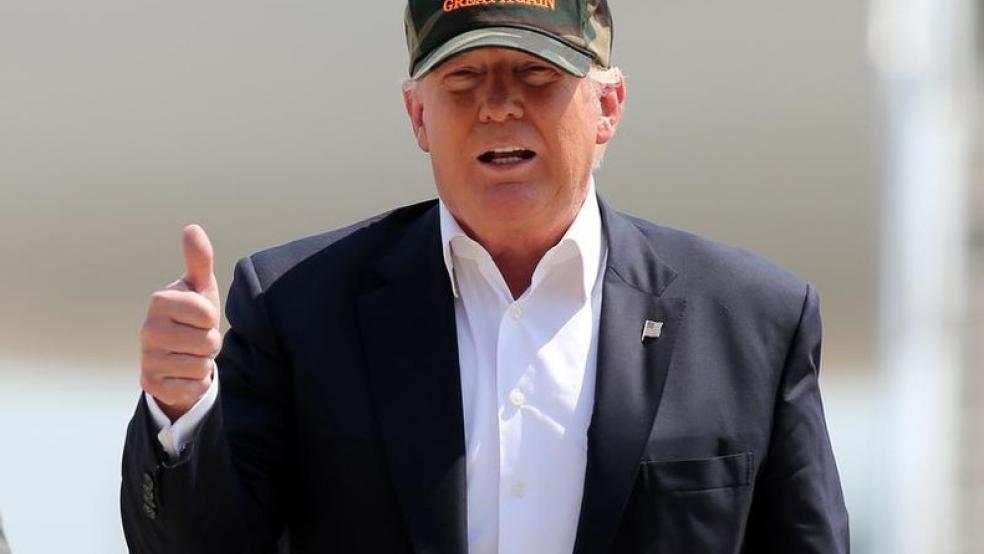

Related: Trump Denounces Globalization, but Trade Experts Aren’t Buying It

Protectionist arguments could easily be applied to interstate commerce. For example, one reason Detroit’s economy became hollowed out is that many car manufacturers chose to operate in lower-cost Southern states. Perhaps if Michigan and neighboring states imposed a high tariff on “imported” Southern cars, more manufacturing jobs could have been retained in Detroit and its environs. And this is just one case; Maine potatoes compete with Idaho potatoes, for another example.

So why not allow states to protect their industries and jobs by keeping out goods from competing states? Because such restrictions ultimately make most of us poorer. The increased competition and greater specialization we get through free trade within the United States gives consumers a wider array of choices at lower costs.

The benefits of free trade don’t end at our coastlines or at the Mexican and Canadian borders, either: The more people and companies included in the envelope of free trade, the more choices and greater value we can all derive.

Related: Trump and Sanders Are Right — Obama’s Trade Deal Is a Dud

When China threw off Maoism and joined the global market system in the 1980s and 1990s, hundreds of millions of people were lifted out of poverty, while American consumers enjoyed everyday low prices at Walmart and other big-box stores, pushing down the price inflation that had been such a nightmare during the 1970s.

Although some Americans resent speaking to customer-service representatives overseas, their low-cost availability means that many consumers can talk to a person rather than being compelled to deal with still-faulty automated phone systems. Meanwhile, the explosion of the offshore services sector in India following Rajiv Gandhi’s 1991 liberalization has elevated tens of millions of Indians above the subsistence living they used to eke out.

So why does international free trade get such a bad rap? Racism undoubtedly plays a role: Africans, Asians and Latin Americans who don’t speak our language and who live in vastly different cultures are usually outside our circle of empathy. If we don’t mind inflicting “collateral damage” on many of these folks with drone strikes, why would we care about their standard of living?

Related: The Foreign Country That Trusts Trump the Most

More important is the fact that the benefits of free trade are diffuse while the harms are concentrated. If Carrier, part of United Technologies, closes a factory in the U.S. because it is cheaper to manufacture air conditioners in Mexico, thousands of consumers each save a few dollars when they buy new air conditioners, but hundreds of Americans suffer a catastrophic loss of income. Meanwhile, the fact that hundreds of Mexican workers enjoy higher incomes and better working conditions does not even enter the U.S. political calculation. Trump and other populists can demonize the company and demand protectionist measures, while individual consumers won’t see enough savings to become motivated.

While Trump is predictably protectionist, mainstream Republicans are hardly pure apostles of free trade. In some cases, they lose sight of its virtues in pursuit of exaggerated national security concerns. For example, the Castro regime in Cuba has not posed a legitimate threat to the U.S. since the fall of the Soviet Union, yet Senate Republicans such as Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz support a continued trade embargo. Republican hawks betray their lack of knowledge when they claim that all economic benefits from lifting the embargo would flow to the regime. Not only would American exporters and importers benefit, but it is obvious to anyone who visits the island that European trade and tourism are benefiting many everyday Cubans. Far more Cubans would earn a comfortable living if they could access the huge U.S. market.

While liberal Democrats champion an opening to Cuba, they have been very resistant to the Trans-Pacific Partnership and other free-trade agreements. An especially disappointing aspect of liberal opposition to free trade is the emphasis on poor working conditions in developing countries. Cutting off trade with poorer nations — ones that liberals are supposedly worried about — will consign more third world families to poverty.

Related: Trump’s Economic Plan Would Be a Disaster for the US Economy

That said, some arguments against TPP are valid. For example, trade agreements normally extend U.S. intellectual property protections to trading partners. Enforcement of these patents and copyrights often does more harm than good. For example, countries entering a free-trade agreement with the U.S. may lose the ability to manufacture certain drugs and consume them at low prices because they resemble pharmaceuticals patented in the U.S. This drives up drug prices internationally and increases suffering among the poor in developing countries who cannot afford overpriced medications.

The U.S. intellectual property system — while initially well intentioned — has become a form of corporate welfare. Many pharmaceuticals receive up to 20 years of protection from low-cost, generic alternatives. They receive this protection even when they did not require a significant research investment. The U.S. should not be abusing free-trade agreements to internationalize this form of corporate welfare: Either intellectual property restrictions in the U.S. should be eased or they should not be imposed on trading partners.

Undoubtedly, free-trade agreements incorporate many other corporate goodies, since CEOs and company lobbyists have so much more access to decision-makers than do domestic and foreign consumers. These kinds of provisions tailored to moneyed and corporate interests should certainly be stripped from free-trade deals whenever possible, but let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater. Rather than demagoguing trade, our leaders should be educating voters about the subtle yet crucial benefits of international commerce and continuing to lower the barriers that stand between us and the rest of the world.