In 1994, economists Larry Mishel and Jared Bernstein of the liberal Economic Policy Institute (EPI) met with the head of President Clinton’s National Economic Council, Robert Rubin. Mishel told that they asked Rubin how the administration planned to increase median wages, a critical failing in the Reagan/Bush years. Rubin replied, “deficit reduction.” He explained how this would reduce interest rates and boost productivity, and that wages would naturally follow.

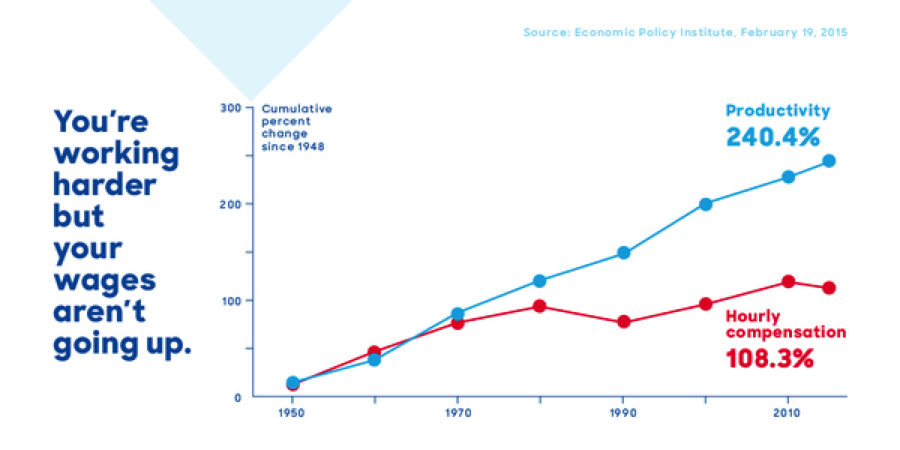

Mishel and Bernstein pulled out a chart. It showed that, for the prior two decades, increases in productivity had not translated into wage gains for the typical worker. This productivity/wage gap showed that something had changed within the economy, with the benefits of growth concentrating in fewer hands. Rubin looked at the chart and said, “I didn’t know that.”

Related: How the Presidential Candidates Would Confront $18.6 Trillion of U.S. Debt

After a brief boom in the late 1990s brought things more into balance, the wage/productivity gap continued to grow after 2000, affecting college-educated workers in addition to blue-collar ones. Whereas in the 1950s and ‘60s wages grew even when unemployment rose, in the last 40 years only super-low unemployment could move the needle on wages.

The updated chart grants perhaps the best visual depiction of rapidly rising inequality, with productivity gains failing to reach the everyday worker and instead funneling into corporate profits and the bank accounts of the wealthy. Hillary Clinton, in fact, has used the above version of the chart extensively in her presidential campaign, making increasing wages central to her economic program.

Perhaps for this reason, the wage/productivity chart has been under attack, with economists and pundits trying to explain away the gap as something not fundamental to our economic story. But Mishel, the originator of the chart, is pushing back, arguing that critics “are denying reality through technical arguments and sleight of hand.” The key point, Mishel says, is that “economic policy cannot be reduced to being about more growth or productivity… they also have to be accompanied by policies that reconnect them to rising wages and benefits for the vast majority.”

This is a critical point. Jeb Bush is basing his entire campaign on increasing economic growth, with the implicit assumption that the rising tide will lift all boats. If only the rich benefit from that rising tide, his entire economic rationale falls apart. In other words, the policy path to improve the lives of American workers hinges on who is right about this chart.

Related: Why Hillary Clinton’s Tax Plan to Soak Investors Won’t Work

Harvard economist Robert Lawrence makes the gap disappear in several ways. First he uses a measure of all workers in the economy, rather than EPI’s use of production and nonsupervisory workers, which makes up about 80 percent of the workforce and mirrors the wage for the median worker. The gap shrinks significantly with just this change.

But that’s misleading, as Slate’s Jordan Weissman points out, because it includes those who are reaping the benefits of this economic age. Using average rather than median compensation is like taking the average salary of five workers in a room when one of them is Bill Gates. The average salary will look pretty robust even if the other four workers in that room are struggling.

In fact, the failure of average compensation to match the typical worker’s compensation is itself indicative of the problem. Without rampant inequality, those two would be in closer comparison. But with compensation so weighted toward the top, you get this gap, revealing a redistribution among workers that has left many behind.

Related: How the Media and You Are Misled by False Data

Lawrence also includes benefits separate from compensation, like health care and Social Security, to reduce the productivity/wage gap. But Mishel points out that wages remain stagnant for the bottom 80 percent of workers, even if you include non-wage benefits. Between 2007 and 2014, the median worker saw wages drop 4 percent, and total compensation — including health benefits and pensions — drop 1.9 percent.

The third effort by Lawrence, picked up by economics writer Matthew Yglesias, argues that the wage/productivity chart uses different inflation indexes to magnify the gap. “The inflation rate for consumers has been rising at a faster rate than the inflation rate for the overall U.S. economy,” Yglesias writes, and this distorts the chart by bringing that discrepancy into the wage and productivity story.

Mishel, while acknowledging this discrepancy — he calls it the “terms of trade” — says that what matters to ordinary consumers is the prices of what they actually buy. So the Consumer Price Index (CPI), the inflation rate based on consumer goods, is the appropriate measure for compensation. “To look at people’s compensation in terms of prices of what they produce is to pretend that somehow people eat machine tools,” Mishel said.

Like the difference between average and median compensation, this gap between the CPI and the overall inflation rate is also indicative of a problem in the economy. “For whatever reason the products people produce are not showing up in their standard of living,” Mishel said. It’s troubling that the cost of health care and education are rising so much faster than wages, straining the ordinary family’s budget.

But that represents only a sliver of the wage/productivity gap. Mishel breaks the gap down based on three factors that have created it. There is the “terms of trade,” and also two measures of inequality: the compensation gap between high- and low-wage workers, and the change in labor’s share of national income. When you break it down this way, you find that compensation inequality represents the greatest share of the wage/productivity gap since 1973. And from 2000-2011, the time after the small boom in the late 1990s, both compensation inequality and the falling labor share of income represent over 84 percent of the difference, with the terms of trade taking up the small remainder. “The main driver of the gap is inequality,” Mishel concludes.

If you believe the Lawrence/Yglesias argument, policies that raise wages are secondary to policies that raise productivity more generally. If you believe the Mishel argument, reconnecting wages to productivity becomes central. Rather than stressing the need to acquire more education and skills, you would support increasing the minimum wage and allowing for more union organizing to put leverage in the hands of labor over capital. You would support proper use of overtime laws to reduce wage theft, and paid family and medical leave to keep wages strong during times of family stress.

Related: Democrats Call for Major Change in Social Security

But if productivity gains just leak out to the wealthy through financial engineering, all the growth in the world won’t benefit the typical worker.

This is why conservatives are desperate to debunk this chart, because it upends their entire conception of low taxes on the wealthy and deregulation as the key to prosperity for all. If wage stagnation isn’t a problem they can continue with their ideology; but if it is, then you have to attack the policies that created the gap.

“The stock market is doing great, CEOs are doing great, the 1 percent is doing great,” Mishel said. “The reason why people have not benefited from growth is because of policy choices made on behalf of those with the most income, wealth and power. Government can be the vehicle to turn this around.”