Activist investors are busier than ever. They are popping up more frequently — undertaking twice as many campaigns as they did only a decade ago, according to McKinsey & Co. They’re also chasing bigger companies.

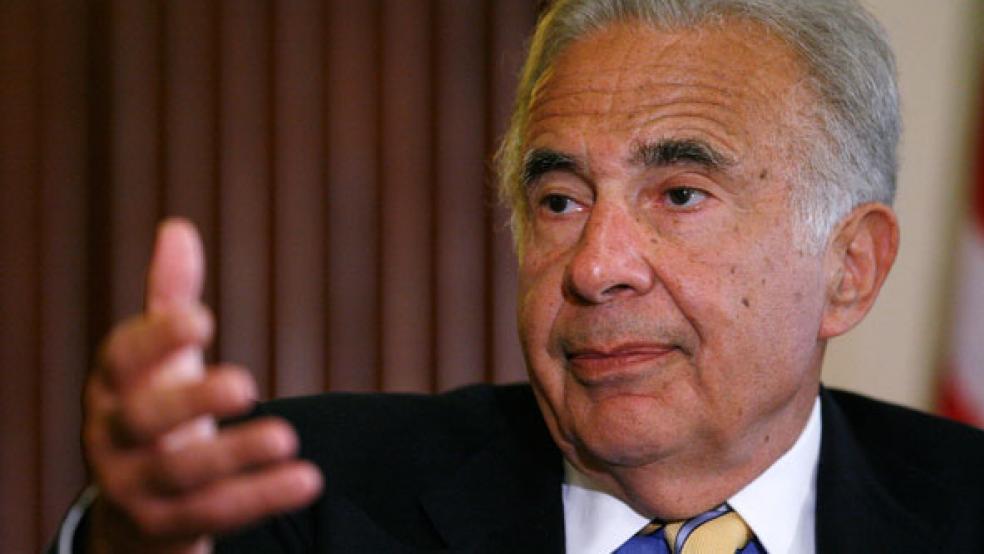

Carl Icahn, for example, has been successful in prodding Apple (AAPL) to use more and more of its cash to buy back stock. Another notably aggressive activist firm, Jana Partners, has announced it has taken a stake in McDonald’s (MCD), becoming one of several investors interesting in shaking up the fast-food chain’s business.

The assets they control have grown, too – to the tune of about $100 billion by some calculations -- and McKinsey says that their assets under management have grown at a faster clip than those of the hedge fund universe as a whole.

Related: What Carl Icahn and Miley Cyrus Have in Common

It’s no shock that all this activity is ruffling feathers. It almost seems like open season on the likes of Icahn or Jeffrey Smith, founder of Starboard Capital, who won Fortune’s title of “the investor CEOs fear most” after he succeeded in parlaying his 10 percent stake in Darden Restaurants (DRI), the owner of Olive Garden, into effective control of the company. Smith wooed and won enough allies among Darden’s other shareholders to enable him to oust the company’s board in the wake of a hotly contested proxy contest last year.

That’s the kind of financial engineering that Larry McDonald, head of U.S. strategy at Société Générale, had in mind recently when he criticized activist investors, arguing that they are hurting the U.S. economy as a whole by forcing corporations to direct capital to shareholders rather than reinvest in ventures that would generate jobs and profits down the road.

But this time it isn’t just the usual suspects who are taking aim at activist investors. Their activities have also attracted the attention of regulators. The Securities & Exchange Commission has launched a probe into the question of whether activists violated securities laws by collaborating with other firms to target underperforming companies and campaign for changes.

Related: SEC Probing Whether Activist Investors Secretly Acted Jointly

Let’s be very, very clear on one big issue: To the extent that activist investors broke securities laws, forming alliances and sharing trading plans and strategies with each other, enabling members of their “wolf pack” to accumulate large blocks of stock in a target company at a lower price than they might otherwise pay — well, bravo to the SEC for cracking down.

Some might argue that, at most, it’s a technical violation of the rules about when you file the disclosure that you purchased a block of stock — but accumulating positions stealthily still amounts to a violation of those rules. Any investor who hoped that the regulators would turn a blind eye and focus instead on more blatant abuses, like insider trading, was simply gambling on the SEC’s willingness to remain oblivious.

The broader question, though — whether activist investors harm the companies they target and hurt the market or the economy — can’t be answered nearly as readily. The problem is that there are so many different kinds of activist investors, pursuing so many different strategies, involved in so many different corporate situations, arguing for so many different solutions, that it’s impossible to paint the entire class as “good” or “bad” in such a sweeping manner.

The activists aren’t trying to win popularity contests in corporate America. And that’s not their role. On the contrary, their raison d’être is precisely to serve as gadflies. To the extent that they can identify what is wrong, propose a solution, win support for their ideas and fix the problems, they make money. They may draw criticism for being too focused on short-term results — but that ignores the fact that so many of their campaigns have succeeded in recent years because they have also won the support of institutional investors who are supposed to have long-term time horizons, such as pension fund managers.

Related: Activist Investors Dig Deep in Energy Company Bets

Activist investors aren’t badly behaving toddlers in a kindergarten playground, throwing tantrums. They are adults making rational and well-informed decisions, in this case, based on what they believe to be investment opportunities created by lazy or incompetent management teams.

Ironically, in some cases those management teams may be the ones that are thinking only about the short term, trying to just guide a business toward its next quarterly earnings release and collect their hefty compensation packages, while failing to develop a long-term strategic growth plan. Who do you think is going to keep a closer eye on the management of XYZ Corp, an activist investor like Bill Ackman or Carl Icahn, or Vanguard Group’s S&P 500 index fund? Exactly.

That’s not to say that activists can’t or don’t do damage to the companies they target. But look at David Einhorn’s involvement with Keurig Green Mountain (GMCR). Einhorn, of Greenlight Capital, didn’t set out to take control of the company or restructure it, but simply proclaimed — frequently and loudly — what he believed to be the company’s business failings. And he established a large short position betting on what he expected would be a decline in the stock’s price. But while the company has made missteps over the years since Einhorn’s 2011 proclamation, Einhorn had long since fled the scene, battered by large losses. He got it wrong; the only damage done in the process seems to have been to his own investors.

Related: From Icahn to Einhorn — 4 Investors Driving CEOs Nuts

Then there’s Apple. On the surface, it would seem to be a poster child for the arguments advanced by Société Générale’s McDonald. Carl Icahn keeps agitating for larger and larger buybacks; Apple obliges, but only to a limited extent. On the other hand, keeping Icahn happy with all those buybacks (not to mention the dividends) is hardly leaving Apple strapped for cash. By some calculations, it has three times the reserves of the U.S. Treasury in cash. Its problem isn’t dealing with an activist investor’s demands. Rather, it’s the apparent dearth of truly compelling investment opportunities, at least when measured against the taxes it would need to pay on about three-quarters of that cash in order to repatriate and reinvest it.

In contrast, McDonald’s is a great example of just why activist investors exist and how they can play a valuable role in the market. Its sales slumped 7 percent last year and profits plunged 15 percent — one of its worst years ever, as competition from newer rivals like Shake Shack (SHAK) as well as veteran competitors like Burger King (BKW) ate into their market. A much-ballyhooed turnaround promises to cut costs and add kale to the menu but ultimately focuses primarily on financial engineering.

That’s where activists can make a difference by stepping in to force real change in a way that long-entrenched board members and managers often are afraid to do.

Related: Boomers, It's Time to Cash Out of This Bubble

If there’s one scenario that is truly disastrous, and succeeds in destroying value and harming the economy, it is what happens when prolonged proxy wars erupt between companies and activists. That’s a surefire way to ensure that no one is paying attention to managing the day-to-day business and instead is running up high legal bills that shareholders end up paying (in one way or another).

The ideas that activists have may be insane, they may be utterly brilliant, and if they win enough support from existing long-term investors, they probably are worth at least considering. Police activists, by all means. But we dismiss them at our peril. With no obnoxious activists in the crowd willing to stand up and call out that the emperor is stark naked, we risk returning to an era characterized by crony capitalism. And that is a far more worrying prospect than anything the activists can offer.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: