All this week, Wall Street has been focused on every word out coming of the mouth of Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen.

The Fed could rate rates for the first time since 2006 as soon as June. Yellen did her best to say as little as possible, continuing the proud tradition of verbal obfuscation from those in charge of monetary policy. But she did reveal a steady confidence in the U.S. economy and hinted that rates could be raised despite relatively soft inflation measures. The overall takeaway: Rates are going up soon.

That could have some unintended consequences for your annual tax return.

Fed policymakers, in their latest individual projections on the path of interest rates, on the whole are looking for rates to end the year above 1 percent. The futures market expects something closer to 0.5 percent. Surely, there will be a reaction to the hikes from the economy and financial markets, both of which have grown dependent upon the flow of the Fed’s stimulus and ultra-low interest rates.

Related: Yellen Defends Fed from Congressional Assaults on the Left and Right

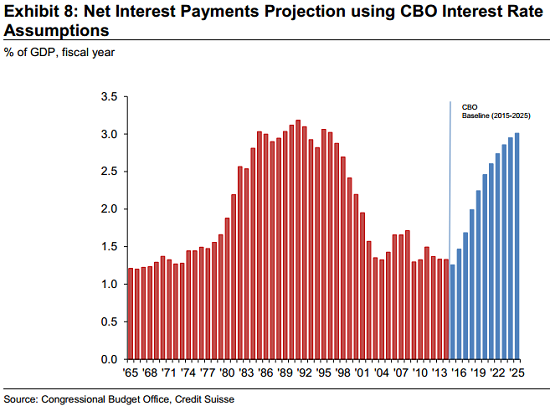

You’ve heard all that before, but there’s also a longer-term point to remember here: Research by Credit Suisse shows that the inevitable normalization of interest rates is going to put the hurt on the national budget — which has been pushed aside as an issue as the annual deficit has eased. The problem is that national debt has done nothing but keep growing and, with the deficit not expected to ever close based on current projections, it's only going to get worse as structural problems, like runaway entitlement costs, remain unresolved.

The Congressional Budget Office puts the annual shortfall, which is projected to fall to a post-recession low of $468 billion this year, back above the $1 trillion mark by 2025. Overall, during the next 10 years, the cumulative deficit is expected to total $7.6 trillion, taking the national debt from $13 trillion now to nearly $22 trillion.

The end result: Higher interest rates could quickly ramp up the national deficit — raising the risk that federal income taxes will be raised in the years to come.

That's because, as the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget noted last month, anticipation of higher spending (again, due largely to the demographic impact of an aging population on entitlement programs), higher interest expense of servicing the national debt and fairly static tax revenue, as a share of the economy, over the next 10 years.

Related: 5 Stupid Tax Proposals Hidden in Obama’s Budget

Washington has shown a preference, in recent years, to tinker with or simply raise taxes rather than trudge through the politically risky minefield that is entitlement reform — despite the fact that there are desperately needed changes to be made in this area, especially in efforts to control health care costs, which were brought to light five years ago by President Obama's 2010 deficit commission. As it is, President Obama's latest budget proposal shows tax revenue steadily increasing, as share of the economy, to the high side of the range seen since World War II.

The CBO estimates that short-term interest rates will rise from near 0 percent now to 1.2 percent next year, 2.6 percent in 2017, and 3.5 percent in 2018, with long-term rates rising from 2.8 percent to 4.4 percent over this period. As a result, net interest payments on the national debt will quickly swell back to a level not seen since the mid-1990s, more than doubling as a share of the economy.

The balance of spending cuts and tax hikes will depend, in large part, on electoral outcomes in 2016 and beyond. But one thing's for sure: Something has to be done.

Related: 10 Surprising Tax Deductions in 2015

Credit Suisse's Jay Feldman notes that while Washington has some fiscal breathing room at the moment and should enjoy a short reprieve on the deficit, assuming no economic downturn and no major changes to current law (which is unlikely given the gridlock between the White House and Congress), any major shock will immediately bring the issue back front and center.

Even Janet Yellen, in her regular testimony to Congress this week, warned that a large and growing national debt could limit the fiscal flexibility needed should the economy tip back into recession and more stimulus spending is required. In her words:

"I also worry that if we were to again be hit by an adverse shock, that there's not much scope to use fiscal policy. It was used in the early years after the financial crisis — we ran large deficits — but in the course of doing that, the debt-to-GDP ratio rose. And were another negative shock to come along, it's questionable how much scope we would now have to put in place even on a temporary multiyear basis expansionary fiscal policy, and I think it's important to deal with these issues — for the Congress to do so."

The irony is that any move by Yellen to bring interest rates back to normal levels, and prevent credit and asset price bubbles as well as economic overheating and inflation, is likely to just make the debt-to-GDP problem worse. Let's just hope we don't have to pay for it on our 1040s.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times:

- Obamacare Tax Traps Are Ready to Grab Your Refund

- 10 Facts the IRS Doesn't Want You to Know

- How Wall Street is Fighting to Rip Off Your Retirement Money