It's getting serious now: On Wednesday, West Texas Intermediate futures tested a low of $46.83 a barrel before rebounding.

That's down nearly 57 percent from the summertime high of $107.68 and pushing toward the depths last seen during the 2008 financial crisis and recession that followed. Wholesale gasoline futures tested a low of $1.31 a barrel.

The wipeout in energy prices has been covered on all angles in recent months — including my recent piece on the negative repercussions for the U.S. economy, corporate earnings, and energy independence. Now, the focus is increasingly turning to how bad the damage could get.

Related: These Five Issues Will Impact Oil Prices in 2015

New estimates from Bank of America Merrill Lynch put the short-term floor somewhere below $35 a barrel — a drop that would represent a decline of nearly 30 percent from here as the market is oversupplied by about a million barrels of oil per day. Options traders are starting to place bets that prices could fall into the $20s in the months to come.

It's clear that a quick reversal isn't coming. OPEC is showing steely resolve in its effort to recapture market share from U.S. shale oil producers. Most oil exporting nations are trapped in a prisoners' dilemma: They all want higher prices as their national budgets feel the pinch. For the likes of Russia and Venezuela, the pain is acute and could well result in an outright currency crisis. But none of them want to make the production cuts needed to align supply with the depressed demand that has resulted from economic weakness across much of Europe and Asia.

Saudi Arabia is best positioned to turn down the taps, but it appears to have spearheaded the oil price war in the first place for both financial and geopolitical gains. Comments from Saudi oil minister Ali Naimi that prices as low as $20 a barrel would be tolerated suggests that Riyadh — despite some palace intrigue surrounding the poor health of King Abdullah — is enjoying the spectacle.

Related: Can the U.S. Boom While the World Busts?

Oil demand is unlikely to soak up the excess supply anytime soon, with Europe stalled, Japan picking up the pieces from its recent sales tax hike and China still trying to control its runaway housing and fixed-asset investment bubbles without pricking its bad debt problem.

The demand situation also has an element of negative self-reinforcement: Bank of America Merrill Lynch analysts note that 50 percent of the global oil demand growth of the last decade has come from oil producing countries. That's a problem, with Russia heading into recession and sovereigns in the Middle East drawing down currency reserves. And besides, they estimate that any response on the demand side would occur with a six month lag anyway.

So to find a price floor, supply will need to be cut from somewhere outside of OPEC. The big state-owned oil producers are an unlikely source, according to the analysts, because they find production is not price sensitive due to price hedging, low cash production costs, tax breaks and currency benefits. At this point, only Canada’s Kearl oil sands project — with a breakeven oil price around $55 a barrel — is at risk. Yet its operator said it would not shut down even if it were cash flow negative. It's all about who can bleed the longest. Brazilian pre-salt fields need just $23 to cover cash costs.

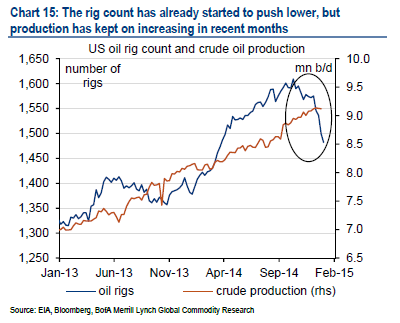

That leaves U.S. shale producers to carry the burden as operating cash flows dry up. But the experience of the natural gas glut of a few years ago, also driven by the success of shale, suggests that operators will at first shift rigs to more profitable fields before cutting output. You can see this in the way rig counts have come down, but production has kept climbing as shown in the chart above.

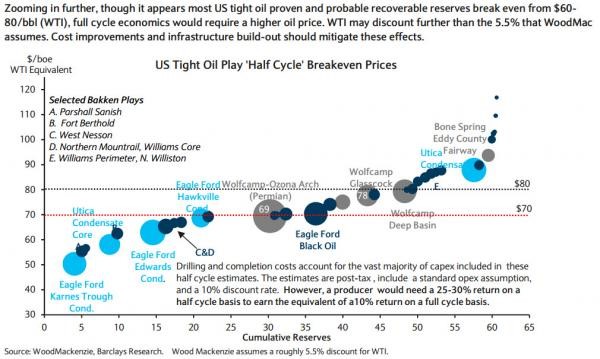

As a result, U.S. production cuts probably won't happen until the drop in new investment, new wells and new rigs starts to flow into current production numbers. All this takes time. But it will happen, with energy consulting firm Wood Mackenzie estimating short-term breakeven prices for U.S. shale at around $70 a barrel.

Related: Collapsing Oil Prices Could Really Mess with Texas

Another wrinkle to the story is that Saudi Arabia is producing less than 10 million barrels a day, holding about 2.8 million barrels a day of production capacity in reserve. If the Kingdom really wants to crush the U.S. energy industry and secure its position as the world's dominant provider of energy well into the future, it could slowly increase production to offset the pullback in U.S. shale oil.

At 12.5 million barrels per day, its budget would come into balance with crude at $77 a barrel, according to estimates by BofA ML. But it can afford to be patient, with $740 billion in foreign exchange reserves (worth 98 percent of GDP), zero debt, and $450 billion in government deposits.

That would keep prices down long enough to drive many marginal, high-cost U.S. producers out of business, with negative results for the U.S. economy, jobs market and high-yield bonds. Those that remained would face a low-return future with oil prices stuck near their cash breakeven costs.

Long story short: In the short-term, prices could very well drop below $35 a barrel to incite U.S. production cuts before recovering into the $70s as Saudi Arabia opens the spigots and captures market share.

In other words, get used to lower gas prices. They'll be here for a while.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: