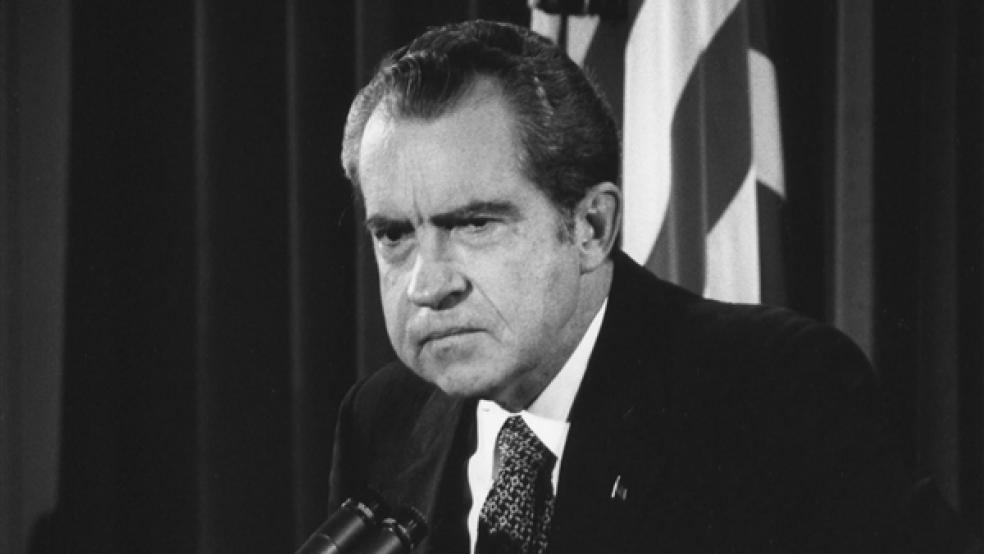

This week, America wraps up the fortieth anniversary of its most dangerous constitutional crises since the Civil War, with little celebration – and arguably no real insight into its lessons. Saturday will mark 40 years since the only presidential resignation in US history, when Richard Nixon stepped down rather than face impeachment for his role in Watergate and other abuses of power. Despite the decades of self-congratulation for the ability of the body politic to police itself, we still have not put aside our fascination and attraction to executive power.

For a country that loves nostalgia, the major anniversaries of Watergate events have attracted surprisingly little notice. The centenary of World War I may be getting more print these days, starting with the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand. Photos and personal narratives have been included in the commemoration of a global conflagration whose resolution produced a horrible World War and many of the problems that plague the West to this day, especially in the Middle East.

Related: Watergate 40 Years Later—Nixon Waged Five Wars

Watergate does deserve some recognition, though, as an imperfect demonstration of the genius of the US Constitution. The founders opted to create a system that would provide checks and balances on the power of the federal government, both within it and between the states and the national government.

The legislative branch would have coequal power with the executive branch headed by the President as a way to keep the head of state from using his power to become a tyrant. The judicial branch would keep both from violating those boundaries, and the competition between those branches would, theoretically, provide the impulse to defend jurisdictions and police against abuses from any of the branches.

For almost all of our nation’s history, the three branches have jockeyed, bristled, and challenged the others for turf protection and to aggrandize their own power. Those fights, while passionate, usually operate within generally acknowledged government authority, such as with presidential recess appointments in one of the most recent cases. Watergate unveiled something much more dangerous – a President determined to usurp the electoral process and use executive power against his political opponents, and afterward to obstruct justice in order to protect himself.

Related: Lost IRS E-mails Point to an Abuse of Power and Cover-Up

Tuesday marked the 40th anniversary of the release of the “smoking gun” tape, which captured Nixon discussing how to block the investigation into the break-in at Democratic Party headquarters at the Watergate Hotel shortly after police thwarted it. That was the final straw for Nixon, who resigned four days later.

However, the focus on those two points ignores the hard work by Congress over more than a year to produce that evidence. Democrats started the probe into Watergate, but eventually Republicans in Congress joined them to defend the balance of power and the rule of law.

The existence of the tapes came to light because of the Republican counsel’s questioning of a Nixon administration official; the counsel was Fred Thompson, who would later become a Senator himself from Tennessee. Congress fought Nixon’s claim of executive privilege on those tapes all the way to the Supreme Court, which ruled against Nixon and forced the release that consigned Nixon to ignominy.

It took both of the other branches, and more than two years of political strife in part during an unpopular war, to bring a rogue President to heel and reinforce the rule of law. If any lesson should have been learned from this, the value and necessity of restricting executive authority and enforcing constitutional restraints should have been at the top of the list. These days, though, we seem to cheer rogue executives for defying those restrictions as an antidote for political stalemate rather than recognize the danger of unchecked power.

Related: House Greenlights Boehner’s Lawsuit Against Obama

Consider the current debate over unilateral executive action on immigration, tax law, and other issues. Obama supporters argue that the current state of politics on Capitol Hill leaves Barack Obama little choice but to start issuing orders for widespread deferrals on enforcement of immigration law. Others don’t see it that way.

The New York Times’ Ross Douthat called it “Caesarism,” but most call it an abuse of presidential authority. In our constitutional system, Congress passes laws and the executive branch enforces them. Even in agency law, where those powers are shared to a certain degree, the executive cannot exceed the grant of authority from Congress, as the Supreme Court just reminded the EPA in June. A stalemated Congress “doesn’t grant the President license to tear up the Constitution,” The Washington Post editorial board warned this week.

Taxes are another area in which Obama supporters are urging “Caesarism,” and sometimes worse. The byzantine and burdensome US corporate tax system has prompted a wave of “inversions,” where corporations relocate overseas in acquisitions and mergers to avoid paying taxes in America. Obama began warning that this violated his sense of “economic patriotism,” saying, “I don’t care if it’s legal” – which is exactly what the executive in the constitutional model should care about.

Related: Obama Goes It Alone (Again), This Time on Infrastructure

Instead, to much cheering, the administration has begun mulling changes to tax laws they can impose unilaterally to punish corporations for acting in a legal manner in reaction to legitimate cost concerns. What happened to taxation with representation?

It’s worth mentioning the IRS targeting scandal, too, which tied up Obama’s political opponents in red tape and endless investigations for the same tax-exempt status that his allies easily acquired. Congress has tried to get to the bottom of that abuse of power, too, but has run into consistent stonewalling from the Obama administration.

When the House Ways and Means Committee tried to force the IRS to produce e-mails from several employees involved in the targeting (first documented by the Inspector General of the Treasury Department), the IRS repeatedly changed its story about whether the e-mails existed – and then had a rash of supposed hard-drive failures and overwritten tapes to explain their failure. On the 40th anniversary of Watergate, it’s worth recalling that one article of impeachment approved by the House Judiciary Committee was the attempted use of the IRS to target Nixon’s political opponents (Article 2, subsection 1):

He has, acting personally and through his subordinates and agents, endeavoured to obtain from the Internal Revenue Service, in violation of the constitutional rights of citizens, confidential information contained in income tax returns for purposed not authorized by law, and to cause, in violation of the constitutional rights of citizens, income tax audits or other income tax investigations to be initiated or conducted in a discriminatory manner.

Related: Obama’s Pattern of Overreach on Executive Power

The familiarity of these events, coupled with the increasing impulse of Obama to abandon constitutional limits, shows that America largely ignored the lessons of Watergate. It’s not enough to be wary of executive power when the opposition party controls the White House, as Republicans belatedly learned in 1974; to defend and protect constitutional government and the rule of law, that vigilance has to exist at all times.

Some of the same voices that shrieked with horror at the threat of the “unitary executive” under George W. Bush seem perfectly comfortable now with Obama ruling by executive fiat rather than governing under the rule of law, as long as it’s only their bêtes noires that get targeted.

Perhaps it’s fitting that the anniversaries of Watergate and the Great World War are so close together, as we seem to have difficulty learning from either.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times:

- If Obama Offers Amnesty to Millions of Illegals, Impeachment May Follow

- The Secret Wall Street Tax You’re Paying but Shouldn’t Be

- The Immigration Problem We’re Not Talking About