Op-Ed: The Obama Administration unprecedented tardiness in submitting a budget to Congress is but the latest stage in the collapse of the federal budgeting process. Instead of a predictable, relatively transparent series of steps that decentralizes decision making, we now have an opaque, ad hoc process largely run by six people – the President, the Vice President and the party leaders of each house.

Since 1921, Presidents have routinely submitted budgets to Congress by late February. In three cases newly elected Presidents submitted budgets later than that, but in all three of these cases, the incoming Administration filed a preliminary document with summary amounts during February. Thus fiscal year 2014 marks the first occasion in 92 years in which Congress did not receive budgetary input from the Administration by the beginning of March.

The President’s budget submission is supposed to initiate a process under which the House, Senate and federal agencies collaborate to enact a budget well ahead of the October 1 start of the federal fiscal year. The government created this process after a period of large budget deficits during World War I. It assumed its current form when a Democratic Congress passed the Budget Act of 1974, wresting greater control from a recalcitrant Nixon Administration.

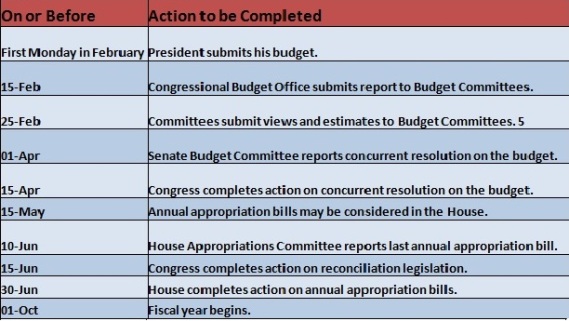

Title III of the Act provides the following budget timetable:

The late submission of the President’s budget means that Congress will either have to start without it or delay its process. While it is true that Presidential budgets are usually “dead on arrival” on Capitol Hill, their voluminous detail is essential raw material to the formation of Congressional appropriation bills.

Before the appropriation process begins, the House and Senate are supposed to agree on revenue and expenditure totals for the upcoming fiscal year. This agreement takes the form of a “concurrent resolution” which is supposed to pass both houses by mid-April. Once the size of the pie has been determined, appropriation committees can then write detailed budgets for each of 13 areas of government they oversee. This procedure gives many members of Congress the opportunity to have input, and it facilitates a vigorous debate over what the federal government should and should not be doing.

In a 2009 Public Administration Review article, budget scholar Irene Rubin traced the breakdown of the budgetary process to the era of balanced budgets in the late 1990s. The rot worsened during the Bush Administration when the House and Senate often failed to approve concurrent budget resolutions. While appropriation bills have been enacted in the absence of concurrent resolutions, the process is complicated by the absence of a pre-agreed total.

More recently, Congress has often failed to pass appropriation bills in time for the budget year, enacting continuing resolutions in their place. Typically, CRs keep an agency’s funding at current levels but lack detailed guidance about how the money is to be allocated. Agency heads thus lack guidance on how to run their departments.

Since 2009, the Senate has repeatedly failed to pass budgets, obliging us to live under a permanent regime of continuing resolutions. The demise of budget processes has been accompanied – at least until recently – by a rise in deficits.

By engaging in the full budget cycle, Congress and the Administration are compelled to take ownership of tax and spending decisions that create deficits. Even if the appropriation process is restored to its former glory, it won’t encompass entitlements. Including federal health programs in the appropriation process would promote better control of medical costs. One reason that the UK has lower health care expenditures (yet higher life expectancy) than the US is that its National Health Service is funded through an appropriations process. The same is true of the US Veterans Health Administration.

Federal budget disarray contrasts sharply with the situation at the state level. Most states balance their budgets and enact them through standard, predictable procedures. While some states, like California and New York, have made headlines with late budget enactment, these are the exception rather than the rule. Further, even a few months’ delay in the passage of a state budget is a far cry from the federal government’s complete failure to enact a budget during the last four fiscal years.

Both Congressional leaders and the Administration have spoken of a return to “regular order” for this year’s budget process. With the unprecedented delay of the Presidential Budget, no such restoration is possible. The prospect of lurching from budget crisis to budget crisis remains the most likely scenario.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Marc Joffe is the Principal Consultant at Public Sector Credit Solutions. He was previously a Senior Director at Moody’s Analytics.