Right-minded Americans agree: every child, regardless of race or circumstance, deserves a shot at success. The question is, how best to further that goal?

President Obama thinks the answer is universal pre-school. In his State of the Union address, he argued that investment in early schooling pays off, boosting graduation rates, reducing teen pregnancy, even cutting down on violent crime.” If only it were that simple.

Anyone who has ventured into the thicket of education reform quickly learns this: it’s not all about schools. Many children start out behind because they were never read to or exposed to the kinds of learning games and stimulating conversation that many families provide. Lots of children are considerably worse off; some are so traumatized mentally (and sometimes physically) by their unstable home lives that they arrive in the classroom completely unable to learn.

A New York-based social services organization called Partnership With Children (full disclosure, I served on their board) works with such children. PWC engages not only with teachers but also with families and care givers. Their efforts are very successful – they help keep kids in school and modify disruptive behavior. But this kind of intensive program is also very costly.

The influence of a child’s home life is immeasurable and likely more determining than early education. That’s likely one reason that Head Start and other programs have been so ineffective. It is also a reason to be skeptical of President Obama’s call for universal pre-school.

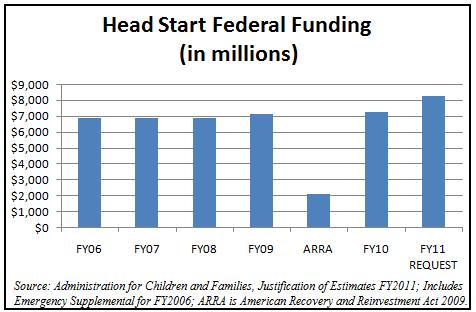

As President Obama must know, reviews of early ed are far from convincing. A study of the Head Start program, into which U.S. taxpayers have poured nearly $200 billion over the past half-century, reveals no lasting benefits for children.

CATO analyst Andrew Coulson examines the pre-school programs in Georgia and Oklahoma – states held up as examples by President Obama – and reports that “neither state has seen a very large move in its scores relative to the national average.” Internationally, some countries that provide universal pre-school, like Finland, score well on educational attainment while others, like Sweden and France, do not do so well.

Russ Whitehurst of the Brookings Institute recently wrote that the growing enthusiasm for preschool education rests on two small studies done thirty or more years ago that tracked young people exposed to intensive early schooling through into adulthood -- the Perry Preschool Project and the Abecedarian Project. Whitehurst notes, “These programs are estimated to have generated positive returns on investment.” But, based on the size and intensity of the programs, and because they were conducted so long ago, Whitehurst concludes “generalizations to state pre-K programs from research findings on Perry and Abecedarian are prodigious leaps of faith.”

Whitehurst notes that the Abecedarian program cost $90,000 per child, compared to the $4,000 to $8,000 per child cost of Head Start or state-funded preschool. These were “hothouse” programs, involving less than 100 children in each – and a far cry from the mass government-funded undertaking envisioned by President Obama.

The president claims that early ed is especially valuable for “poor kids who need help the most.” He is right that they are our neediest children – and especially those in minority communities who are most vulnerable to the dreadful cycle of failure in school and in life. He neglected to mention that the cycle begins with the breakdown of families, a collapse no amount of preschool spending is likely to fix.

The president briefly endorsed “strengthening families” and “doing more to encourage fatherhood because what makes you a man isn’t the ability to conceive a child; it’s having the courage to raise one.” It was a welcome toe in controversial waters. The reality is that the “attainment” gap starts not with a lack of early schooling, but with single parenting.

According to the U.S. census, the poverty rate for single parents with children in the U.S. in 2009 was 37.1 percent. For married families the rate was only 6.8 percent. The chance of a child ending up poor declines by 82 percent when raised in a two-parent family. As the Heritage Foundation’s Robert Rector reports, “Some of this difference in poverty is due to the fact that single parents tend to have less education than married couples.” Even adjusting for that factor “the married poverty rate will still be more than 75 percent lower.”

The trends are not encouraging. As Rector points out, when the War on Poverty was launched by Lyndon Johnson in the mid-1960s, only 6 percent of babies were born out of wedlock; in 2010 the figure was 40.8 percent. This phenomenon is most pronounced among blacks. Some 80 percent of first black children are born to single mothers. The figure for Hispanics is 53 percent; whites, 34 percent; and Asians, only 13 percent.

The question is: should we spend an estimated $100 billion over ten years making preschool more widely available, or should we spend those funds trying to cut down on teen pregnancies and single parenting? What can be done?

The Brookings Institute’s Ron Haskins has proposed amending welfare rules so that single mothers do not automatically lose benefits when they get married, a rule which acts as apowerful deterrent. Heritage’s Rector suggests public education programs aimed at teaching the value of marriage in low-income communities and in schools and in federally-funded birth control clinics. Such measures are only starting points, but perhaps more effective than expanding pre-school.

President Obama’s pitch for early ed is not so much a remedy as a thank-you to the teachers unions who were so instrumental in his reelection. With births at their lowest level since 1920 and the nation turning out twice as many elementary school teachers as we need, the suggestion that we build in another layer of education was politically brilliant but at the end, another ill-advised use of taxpayer money.