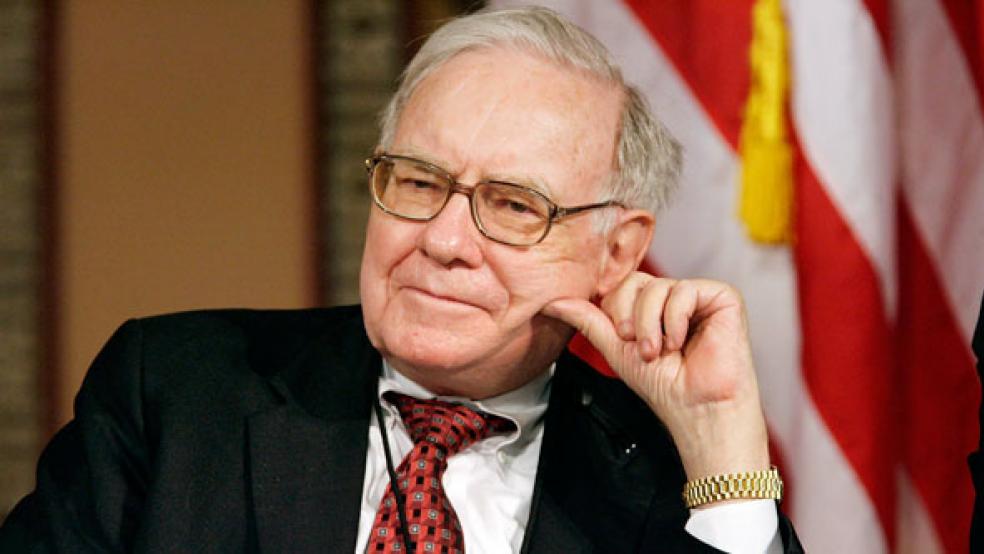

Warren Buffett has been a critic of companies that use their capital to buy back stock instead of investing for future growth. He also hasn’t been a big fan of millionaires and billionaires trying to minimize their taxes. None of that stopped him from spending about $1.2 billion to buy back 9,200 Class A shares of his Berkshire Hathaway holding company from what the firm described as “the estate of a long-time shareholder.”

Buffett has famously championed the idea that the rich should pay more in taxes and just this week signed on to a letter calling for higher taxes on large estates. Yet his purchase of 9,200 Class A Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE: BRK.A) shares at a slight premium of $131,000 a share was a generous holiday gift to that anonymous shareholder; he (or she) or his heirs will be able to lock in 2012 estate tax rates on the transaction. Even more unusually, Buffett announced he’d pay more than he has historically – up to 120 percent of book value – to purchase more of his company’s stock.

But then, the looming fiscal cliff seems to be changing the minds of many market participants – or at least tempting them to do things that they haven’t usually done, like Buffett. In some cases, the cliff has even led executives and investors to do things that don’t correspond terribly well with the principles of corporate finance or investment logic. Individual investors are dumping shares of some dividend-paying stocks, causing some of their financial advisors to gripe that they are throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

“Yes, a higher tax rate will eat into returns slightly, but some of the stocks my client insisted on selling will still do better for them – even after where taxes probably will be – than the alternatives we have selected,” said one such financial advisor, who didn’t want to be named in case his client spotted this column. “Honestly? It seems kind of irrational to me, but sometimes logic just doesn’t work, and if it isn’t actually going to damage their financial plan, it’s not worth going to the mat over.”

Then there is the growing number of companies out there who are choosing to pay out special dividends between now and the end of the year, in some cases raising debt to do so. The probability that future dividend income streams will be taxed at the levels that they were until a decade ago has prompted companies to front-end load those distributions, getting in ahead of the end of the year.

Still, it’s one thing for a company siting on a mountain of cash – think Apple (NASDAQ: AAPL) – to decide to hand back some of that capital. After all, the raison d’être for special dividends (and buybacks, too) is that a company can’t find a better use for its cash – one it considers likely to earn a return greater than its cost of capital – and so is opting to return that capital to its investors.

It seems as if CFOs at companies like Costco (NASDAQ:COST), Humana (NYSE:HUM), and Carnival (NYSE: CCL) skipped that corporate finance class. True, companies can rationalize borrowing to pay special dividends by telling themselves that interest rates remain so low – Brown-Forman (NYSE: BF.B), for instance, was able to raise its own $750 million of debt to finance a special dividend at rates of between 1 percent and 3.76 percent. But even in an era of cheap debt, leveraging up the balance sheet reduces a company’s future financial flexibility. What happens if it spots a great acquisition down the road, but rates have climbed or raising new debt would be more costly because its credit rating has been cut?

The special dividends are great holiday treats for investors, of course, at least some of whom are likely to pocket them and then, whistling merrily, hit the sell button on at least some of the companies that issued these payouts.

None of this is utterly rational. Did investors truly expect hefty special dividends from companies without enough cash on their books to pay for them outright? None of those investors, of course, will wave aside the payout and politely decline, but would the companies have lost credibility with the market by simply declining the opportunity to jump aboard the bandwagon? Would Warren Buffett really have cared if his long-term investor was annoyed by his refusal to pay a lower price for the Berkshire Hathaway stock, staying in line with his traditional policy on the matter?

All this is, of course, being driven by uncertainty surrounding future tax rates, and the assumptions (almost certainly correct) that those rates will climb in the New Year. It will be a relief when that uncertainty turns to certainty, and market participants focus less on the countdown to the “fiscal cliff” and more on long-term market fundamentals.