f asked what policies Mitt Romney would enact that are significantly different from those Barack Obama would enact in a second term, I expect that most people will say that Romney will cut taxes, whereas Obama will not. Therefore, we can say that the election is more about tax policy than any other issue.

The first thing to understand is that Romney’s plan would not cut taxes at all, at least in principle. It is a revenue-neutral tax reform. He repeatedly says that he would raise exactly the same amount of revenue after his plan is implemented as would be the case without his plan.

While it is true that Romney says he will cut tax rates by 20 percent, this is not by any means the same as saying he will cut taxes by 20 percent. The revenue lost by lowering tax rates would be replaced by raising taxes by taking away peoples’ tax deductions. Some people will get a net tax cut, others will likely see a large net tax increase.

It is impossible to say who will get a tax cut and who will get a tax increase because Romney won’t say which deductions he will eliminate to pay for his rate cut. Obviously, he knows that there are many people planning to vote for him who wouldn’t if they knew their taxes would rise under his plan.

To prevent this from happening, he talks in broad generalities and emphasizes the 20 percent rate cut, hoping that people will think their taxes will go down by 20 percent when this is clearly not what he is proposing.

As a number of analysts have pointed out, there is no way that Romney can possibly make the numbers in his plan add up is unless he abolishes very popular deductions such as that for mortgage interest, state and local taxes, and charitable contributions. Obviously he would lose a massive number of votes if every homeowner, churchgoer, and resident of a high-tax state thought this would happen. Therefore, exactly what deductions would be eliminated has been kept a secret from voters.

Indeed, there isn’t much support even among Republicans for eliminating deductions necessary to pay for Romney’s rate reduction. The Republican Party platform adopted at the same convention where Romney was nominated says that under no circumstances should the charitable contributions deduction be touched. And just this week, Senator Marco Rubio of Florida, a rising star in the GOP, objected to any tax plan that restricted mortgage interest or the exclusion for health insurance as well.

Said Rubio, “Do you really want to hurt charitable giving in a country when you are saying that you want to rely less on government and more on private institutions to deal with these issues? And how are you going to raise taxes on people on their health care premiums when you are saying you want there to be a system in place where folks can have more control over their own money?”

In response, Romney put forward a new tax plan in recent days suggesting that he might not raise taxes by eliminating specific deductions that are too popular to touch, but rather by capping all of a taxpayer’s deductions by some amount. At first he put forward the hypothetical figure of $17,000 per taxpayer, but at the presidential debate on Tuesday he raised that number to $25,000.

In short, a taxpayer would add up all his deductions for charity, mortgage interest, state and local taxes, medical expenses and whatever else he or she is entitled to and if the amount is over whatever figure Romney has decided upon then the amount above that would not be deductible.

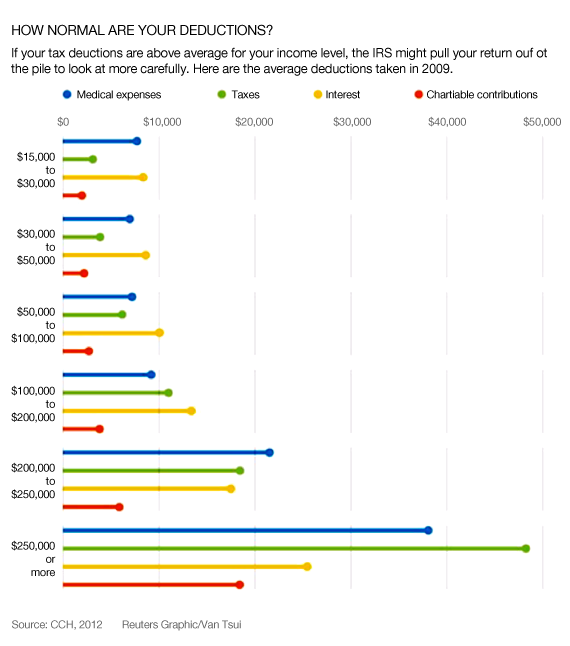

Taxpayers thinking they will get a tax cut from the Romney plan would be advised to check their tax returns first. According to data released earlier this year, taxpayers who declared between $50,000 and $100,000 of income in 2009, claimed, on average, $7,269 for medical expenses, $6,247 for taxes, $10,133 for interest and $2,775 for charitable contributions. That sums to $26,424 – well above both figures Romney has put forward.

To be sure, taxpayers would simultaneously benefit from lower tax rates. But keep in mind that we are talking about statutory rates, not the effective rates that people actually pay. Whether a particular taxpayer will come out ahead or lose from the Romney plan depends on their particular circumstances.

On Wednesday, the Tax Policy Center published estimates of the impact of the Romney plan under both the $17,000 and $25,000 deduction cap scenarios. Note, “current law” estimates assume that the Bush tax cuts expire at the end of this year on schedule, “current policy” assumes that they are extended. Romney has said that he wants the Bush tax cuts extended permanently in addition to his proposed rate cut.

What the TPC found is that almost everybody gets a tax cut under either proposal because capping deductions at either $17,000 or $25,000 doesn’t raise nearly as much revenue as is lost by cutting rates 20 percent. The gross revenue reduction from the Romney plan (including other tax cuts he has proposed in addition to the 20 percent rate cut) is at least $5 trillion over 10 years, whereas capping deductions at $25,000 brings back only $1.3 trillion and capping deductions at $17,000 would raise only $1.7 trillion.

Indeed, even if every single deduction is completely eliminated for everyone, it would only cover $2 trillion of the gross cost of the Romney plan, leaving a net tax cut of $3 trillion. That is to say, the deficit would be $3 trillion higher under the Romney tax plan. Contrary to his oft-repeated promise that he would raise the same revenues, he would not – or even come close.

Readers can judge for themselves whether Romney is stating a falsehood when he says his tax plan is revenue-neutral or whether he is simply clueless about how his plan actually works. Neither option reflects very well on a candidate promising to bring honesty and business acumen to government policy. Clearly, a business deal that would cost $5 million and only recoup $2 million is one that Romney would have rejected out of hand in his days at Bain Capital.

Bruce Bartlett's latest book, The Benefit and the Burden: Tax Reform—Why We Need It and What It Will Take, served as a domestic policy adviser to President Ronald Reagan and as a Treasury official under President George H. W. Bush.