Why do students go to college? A new poll has a one-word answer: money. That’s one of the findings in a broad Gallup survey of college admissions officers done for Inside Higher Ed. The admissions officers seem to believe that those planning to attend college view it largely as a signaling device that directs the best and brightest young Americans to the best and highest- paying jobs.

It is not primarily about acquiring knowledge (“human capital”), critical learning or leadership skills, or better perceiving the difference between right and wrong, but more about achieving the American Dream of a comfortable, moderately affluent life.

Admission directors at public four-year colleges are on board with these expectations. They agree:

• That “parents of applicants place high importance on the ability of degree programs to help students get a good job.”

• That getting a good job is very important to prospective students.

• That at all forms of higher education institutions, schools are putting more emphasis on job placement.

FAST-GROWING JOBS: NURSE, CASHIER

All of this relates to the new labor-market reality that Mitt Romney actually referenced in the first presidential debate: half (more or less) of recent college graduates have had a decidedly unfavorable post-graduate employment experience. This problem is not going away any time soon: 30 percent of adults already have college degrees, and the proportion is rising.

Yet, with the exception of nanotechnologies, relatively high paying technical, managerial and professional jobs account for a smaller proportion of the labor force –and that proportion is not growing rapidly. In contrast, the number of nurse’s aides and cashiers is growing faster. Big-box discount stores, beauty parlors, and bars collectively employ more persons than sophisticated firms in the STEM disciplines (science, technologies, engineering, and mathematics) or high finance. So one of my favorite and talented recent graduates is now working at Lowe’s, not the public-policy think tank for which he is eminently suited.

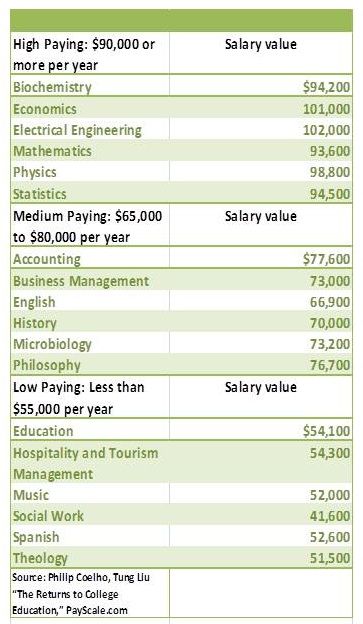

There is a hint in all of this that colleges must strive to be more “vocational,” to stress practical majors which provide skill sets needed in the real world. Labor market data suggests there may be a grain of truth to this, but a look at an interesting new study by Philip Coelho and Tung Liu of Ball State University shows that many traditional liberal arts majors do just fine in the labor market. Look at the table below (which I greatly abridged), where Coelho and Liu use PayScale.com data to report mid-career earnings by academic major.

While STEM disciplines like engineering, math and physics dominate the very highest-paying majors (many averaging over $100,000 a year by mid-career), graduates in history average almost as much as those in business management ($70,000 vs. $72,100), and philosophers ($76,700) actually make more. English majors slightly out-earn those majoring in hotel business management. Art history majors actually average more than those majoring in human resources.

It appears to be a vastly overblown notion that a well-rounded individual majoring in a non-vocationally oriented field in the arts or humanities is destined to do poorer than the business and communication specialists. The per capita student endowments of Williams and Amherst are among the highest in the nation, in spite of the fact their generally affluent graduates are mostly majoring in fields with little direct labor-market relevance.

However, I think colleges are threatening to lose their very critical advantage that comes from employers putting a value on a piece of paper (bachelor’s diploma) sometimes worth a million dollars or more. As administrative staffs have proliferated in recent years, the placement offices of schools have only modestly shared in the largess. Schools have been far more likely to add sustainability coordinators and diversity specialists rather than job placement professionals.

TOO LITTLE, TOO LATE

Yet being a highly expensive screening device, colleges need to maintain their economic advantage by seeing that their graduates are matched with employers. Some for-profit schools do this well, but the traditional university all too often views dealing with the corporate world as vaguely demeaning and dirty. Belatedly, many schools are promoting internship programs, but in some cases it is too little, too late.

No amount of placement or internship hype, however, can solve the basic mathematics problem –one-third is a larger number than one-fifth. Roughly a third of adults have four-year degrees, but only one-fifth of jobs are in the relatively high-paying fields. That is why we have a small army (115,000) of janitors with bachelor degrees.

Rather than adding two million more enrollees at community colleges (as President Obama advocated in the first presidential debate), maybe we should have two million fewer Pell Grants or student loans in order to help, in the long run, to restore balance between supply and demand for college graduates in high- paying fields.

Richard Vedder directs the Center for College Affordability and Productivity, teaches economics at Ohio University, and is an adjunct scholar at the American Enterprise Institute.

This article was published originally in Minding the Campus.