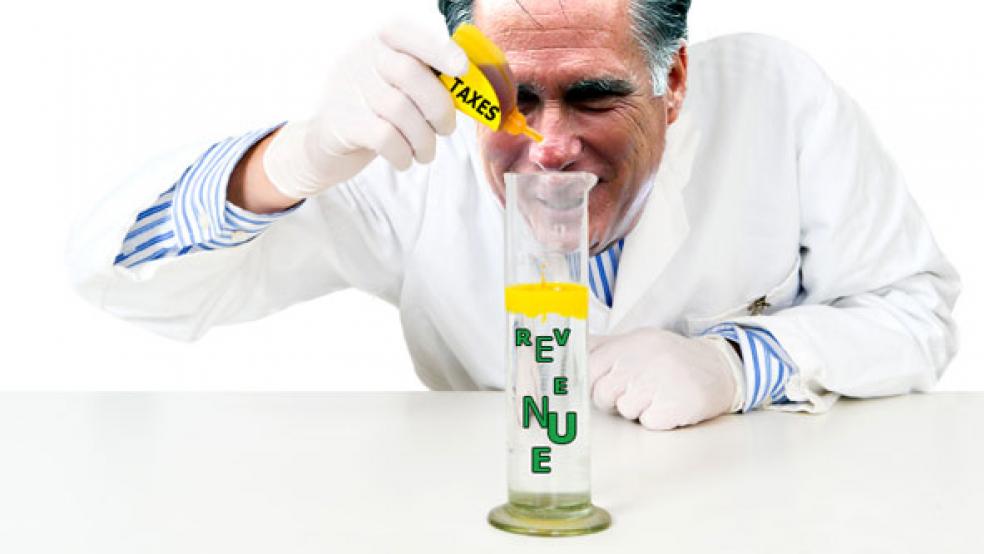

Republican Mitt Romney’s signature campaign issue is his plan to cut tax rates by 20 percent across the board to jumpstart the economy. Should he be elected, what are the odds that he will be able to keep his promise? Not very great, in my opinion. Here’s why.

Let’s start with the basics. Romney won’t take the oath of office until January 20, 2013. Until then, Barack Obama will continue to be president. The most Romney can do is use the transition period to put flesh and muscle on the skeleton of a tax plan that he has so far put forward.

Romney’s designated staff will have access to the Treasury Department’s tax staff and can get them working on drafting legislation to implement his tax plan, prepare an official revenue estimate, distribution tables and so on. But first he will have to designate people to work with, and possibly at, Treasury and provide them with more guidance on the details on his tax plan than have been made public thus far.

It’s possible that Romney already knows who his Treasury secretary will be, but I doubt he has given any thought to who might be the assistant secretary for tax policy. But clearly someone with deep knowledge of the tax code and tax analysis is going to be needed to shepherd his tax plan into shape for congressional action.

Of course, Romney has the option of just giving Congress some general idea of what he would like and let the congressional meat grinder go to work. This is basically what the George W. Bush administration did with all of its tax initiatives. But that was when Republicans controlled both the House and Senate and he could be reasonably certain that the end result would be close to what he wanted.

Romney won’t have the same luxury Bush had. At this point, Democrats appear very likely to continue controlling the Senate and even have an outside chance of House control. Even if they fail in the House, the Republican majority is almost certain to shrink. And should Democrats lose the Senate, Republican control will be razor thin and Democrats will easily have the 40 votes needed to filibuster whatever they feel like.

These obstacles are not insurmountable, but will require Romney and his team to work a lot harder to enact his tax plan than he often implies on the campaign trail. Even Ronald Reagan’s tax plan took until August to achieve enactment, and it’s doubtful that he would have been successful had he not suffered an assassination attempt that shifted congressional support in his favor.

But there are many other complications as well. For one thing there is the much-feared fiscal cliff that will occur at the end of this year when all the Bush tax cuts and a variety of so-called tax extenders expire, plus large automatic spending cuts take effect. While it is possible that Obama and the lame duck Congress will delay the impact of the fiscal cliff, this is by no means assured.

Budget analysts are skeptical that House Speaker John Boehner has the votes to stop the fiscal cliff on his side of the aisle. He’s not likely to get much help from Democrats, even if urged to do so by Obama, in repayment for the games Republicans played last summer over raising the debt limit.

And in the event that Romney wins the election, Obama may decide to dump the whole problem in his lap. Although it is theoretically possible that Romney and Obama could work together during the transition to come up with some bipartisan solution, history does not provide any precedent for that. For example, in the fall of 2008, as the economy was crashing, Bush made no effort to reach out to Obama and Obama was in no position to exercise leadership when he had no staff people in place or the authority to do anything other than observe.

Additionally, Romney will have the challenge of making all his various tax and budget promises add up. His basic problem is that he has made three key promises that are in conflict with each other. He has said he will cut statutory tax rates by 20 percent across the board, that he will eliminate enough tax deductions to keep total revenues the same as they would otherwise be, and he will maintain the existing distribution of taxation among income classes.

A number of economists have pointed out that all three of these promises cannot be kept simultaneously. The core problem is that even if every single deduction is eliminated for those making more than $200,000, they will still get a large net tax cut. Therefore, Romney will either have to raise taxes on those making less than $200,000 or blow a hole in the deficit.

When one of Romney’s economic advisers, Kevin Hassett of the conservative American Enterprise Institute, suggested that if the numbers don’t add up then Romney would scale back his tax cut for the rich. Romney immediately denied he would do any such thing.

One big problem in analyzing the Romney tax plan is that he hasn’t put enough specifics on the table to allow it to be properly evaluated. For example, he has refused to name a single deduction that he would eliminate to pay for his rate reduction. When asked about the mortgage interest deduction, he denied that it was on the table and the Republican platform says that the charitable contributions deduction will not be touched.

Recently, Romney voiced support for an idea proposed by Republican economist Martin Feldstein to simply cap all deductions. Romney has suggested that he would limit every taxpayer’s total deductions to $17,000. It is not yet known whether this comes anywhere near making Romney’s numbers work.

Finally, there is the overall budgetary and economic environment Romney will inherit in January. Even without the fiscal cliff, growth may still be slow and the budget deficit will still be a problem. He will be under intense pressure to offer some short-run stimulus for the economy and make good on his promise to reduce the deficit. How he will juggle these competing priorities will, at a minimum, be very difficult.

One way or another, the political factors clouding the tax and budget outlook will begin to clear in a little over three weeks. At least then we will know who our next president will be and the composition of the next Congress. Until then, all we can do is speculate.