At some point during the recovery, the Fed may face an important decision. If the inflation rate begins to rise above the Fed’s 2 percent target and the unemployment rate is still relatively high, will the Fed be willing to leave interest rates low and tolerate a temporary increase in the inflation rate?

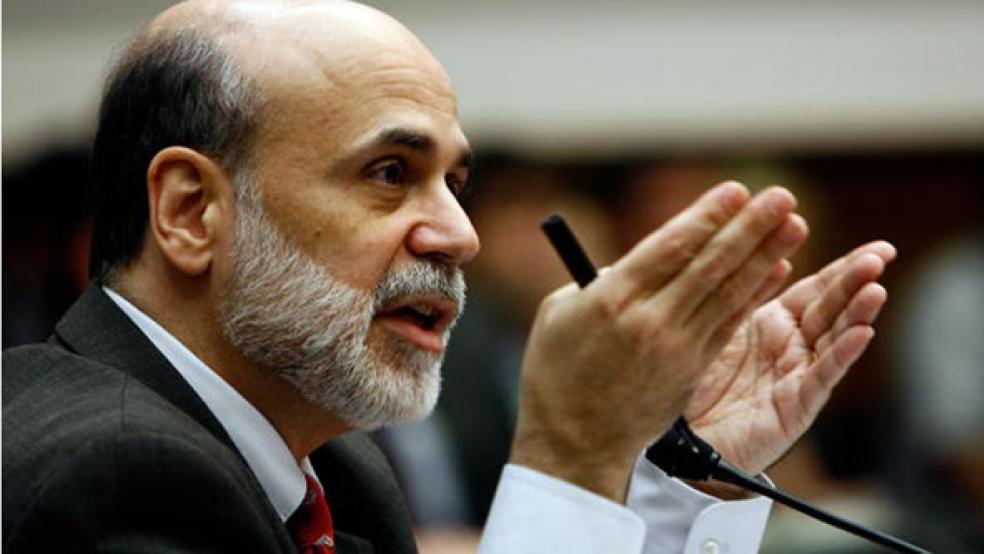

Probably not. Even though higher inflation can help to stimulate a depressed economy, Ben Bernanke, Chairman of the Federal Reserve, is not in favor of allowing higher inflation because it could undermine the Fed’s “hard-won inflation credibility.” And recent Fed communications seem to be setting the stage for the Fed to abandon its commitment to keep interest rates low through the end of 2014. This adds to the likelihood that the Fed will raise interest rates quickly if inflation begins increasing above the 2 percent target even if the economy has not yet fully recovered.

RELATED: Fed Faces New Challenge from the Left

As I’ll explain in a moment, that’s the wrong thing to do. But first, why does the Fed put so much value on its credibility?

An abundance of credibility allows the Fed to bring the inflation rate down from, for example, 5 percent to 2 percent at minimal cost to the economy. It also makes it less likely that inflation will become a problem in the first place, because high credibility makes long-run inflation expectations less sensitive to temporary spells of inflation. So maintaining high credibility has substantial benefits.

Does this mean the Fed should do its best to keep the inflation rate at 2 percent?

Sticking to a 2 percent target independent of circumstances is not optimal. There are times, such as now, when allowing the inflation rate to drift above target would help the economy. Higher inflation during a recession encourages consumers and businesses to spend cash instead of sitting on it, it reduces the burden of pre-existing debt, and it can have favorable effects on our trade with other countries.

If inflation begins to rise before the recovery is complete the Fed could, for example, announce that it is willing to allow the inflation rate to stay above target temporarily in the interest of helping the economy. But once unemployment hits a pre-set rate, for example 6.25 percent, or core inflation rises above some predetermined threshold, for example, 5 percent, then, and only then, will the Fed step in and take action. And it should leave no doubt at all about its commitment to step in if either condition is met.

RELATED: Real Recovery: America’s Debt Is on the Decline

But there is a tradeoff to consider. Allowing a temporary spell of higher inflation during the recovery does pose some risk to the Fed’s credibility. I think the risk is small precisely because the Fed has been so careful to establish its inflation fighting credibility in the past. And the risk is even smaller with the 5 percent limit on the Fed’s tolerance for inflation described above. But the risk is there.

When the economy is near full employment, the tradeoff between the risk to credibility and the prospect for a faster recovery is unattractive. There’s little room to stimulate the economy and hence little room to benefit from a higher inflation rate. And the loss of credibility is potentially large because creating inflation in such a circumstance – when the economy is already growing robustly – would be viewed as irresponsible. Thus, the tradeoff is negative overall.

But when there is considerable room for the economy to expand, as there is now, the potential benefits from the increase in employment that this policy is likely to bring about are much larger. Why the Fed places so little weight on these benefits when unemployment remains so high is a mystery.

In comparison to the risks to credibility, which are smaller than they are near full employment, the benefits are large and the tradeoff is positive rather than negative. There does come a point when the tradeoff is negative again – hence the 6.25 percent unemployment and 5 percent inflation triggers described above – but in the interim we should be willing to allow modestly higher inflation. I have no doubt that, once the economy has finally recovered, the Fed will ensure that the inflation rate is near its target value, so long-run credibility is not at risk.

If inflation begins to rise before the economy has fully recovered, the Fed shouldn’t react as though its world is coming to an end and immediately begin reversing its stimulus efforts. The resulting increase in interest rates would make the recovery even slower. In fact, given the net benefits that more inflation would provide right now, the Fed should try to raise the inflation rate through additional stimulus programs.

Unfortunately, the Fed has made it abundantly clear that’s not going to happen. But at the very least the Fed should continue its present attempts to help the economy, even if that means a temporary increase in the inflation rate.