For months, the Obama administration has told American voters that the nation had turned the corner on a stagnant recovery. Job creation picked up in December, January, and February, averaging a decent if unspectacular 217,000 jobs added monthly during that period.

It seemed as though the economy would provide the White House with momentum heading into a tough election fight -- not just for the White House but also for the Senate where Democrats have to defend 23 of the 33 seats up for election this year. Evidence of success from Barack Obama’s economic policies might keep both in Democratic hands, especially as voters start taking the election seriously this summer.

A month ago, the March numbers dashed those hopes. Job creation slowed significantly to 120,000, and a few weeks later, the GDP report for the first quarter provided some explanation. Growth slowed from a pedestrian 3.0 percent in the fourth quarter of 2011 to a stagnation-level 2.2 percent. Still, the White House suggested that this was merely a hiccup in an overall improvement for job creation and economic growth. One month does not a trend make, after all.

Yesterday, though, the monthly report from ADP, the nation’s largest private-sector payroll management firm, indicated that April might actually be worse than March. ADP produces a projection based on a sample of a half-million of its anonymous customers, comprising 21 million payroll jobs.

That’s not unlike the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which derives its job-related data from two surveys, one of households and the other of businesses. Gallup has a semi-monthly report that uses a sample roughly half that of the BLS’ 60,000 households, but samples continuously throughout the month rather than at one fixed time. Between the three, analysts can get a pretty good idea of how well the economy is creating jobs.

In its April report, ADP estimated that the private sector added only 119,000 jobs, just a little over half of their estimate in March (201,000). For the first time since September, ADP estimated a net job loss in manufacturing, down 5,000 jobs. Construction also lost 5,000 jobs, the first losses in seven months, at a time of year when one would expect construction firms to need more employees. Large companies practically stopped hiring altogether, adding only 4,000 jobs -- the slowest performance in six months.

Gallup’s last report is a little more dated, but no more optimistic. The mid-month numbers show seasonally-adjusted unemployment sharply increasing from March’s 8.1 percent to 8.5 percent in April, while the percentage of Americans working part-time while wanting full-time work rose from 9.6 percent to 9.9 percent. Gallup warns that the numbers could “indicate a significant reversal in the recent downward trend of the government's seasonally adjusted unemployment rate.”

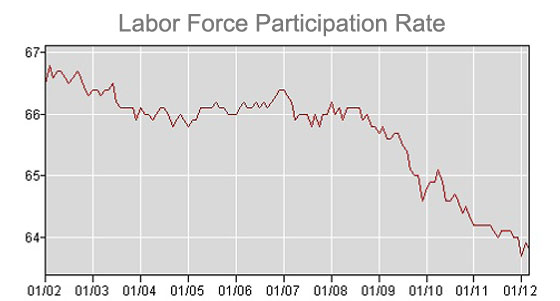

The actual jobless rate will rely on a quirk in the BLS measurement, as CNN pointed out in its coverage of the ADP report: “The unemployment rate is not expected to fall beyond its current 8.2 percent, unless more workers leave the labor force.” When people leave the work force, it improves the topline unemployment rate, a statistical point that hadn’t been an issue until the aftermath of the past recession. In order to understand that well-publicized rate, one has to keep in mind that it describes an increasingly smaller work force, as this BLS chart of civilian participation in the workforce over the last ten years demonstrates:

This hides the effects of poor job creation. Had the participation rate remained constant from pre-recession levels, the jobless rate would be around 12 percent at the moment. The BLS uses the same measures as it always has, but this particular calculation only works for comparative purposes in a stable working population. Even from the point of the recovery’s beginning in June 2009, we clearly have continued erosion.

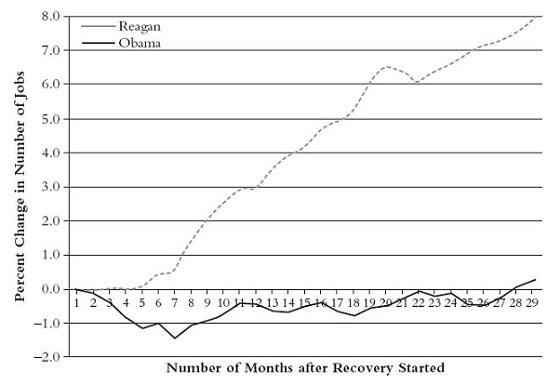

In their book Debacle, John Lott and Grover Norquist compare the Obama recovery to that of the 1982 recovery under Ronald Reagan. The double-dip 1980-81 recession was longer and produced higher unemployment than that of the so-called Great Recession, and it followed a decade of stagnation, “stagflation,” high interest rates, ill-considered wage and price controls, and energy shocks. Yet in the 29 months that followed the 1982 recovery, the American economy expanded jobs by 8 percent. In contrast, the Obama recovery in the same period only grew jobs in the US by 0.25 percent:

The engine of job creation has been derailed. We are now years behind the curve, and as the economic indicators keep showing, we continue to do no more than tread water. Factory orders and durable goods hit three-year lows in March, and so it will come as no shock if jobs match that pattern. We will see whether the pessimistic indicators accurately predict the BLS employment report tomorrow. Given the rise of weekly initial claims for unemployment benefits and the recent history, the betting will be toward another month of slow job creation rather than a return to the relatively more robust winter growth figures.

What happens when job creation fails to maintain any momentum? The closer the election comes, the worse it is for President Obama. His campaign has lately occupied itself with just about every topic except the economy and job creation, including a silly attack on Mitt Romney as insufficiently ruthless to kill Osama bin Laden after months of painting him as a ruthless killer of jobs as a Bain executive. Whether it’s contraception or Swiss bank accounts, the Obama campaign seizes on any momentary distraction it can find to avert attention from jobs and the economy.

A poor report tomorrow will make that impossible, at least for a few days. The mild momentum of the winter would have given way to another stagnant spring, the third in a row, as David Gregory pointed out to Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner on Meet the Press in April. Even a mildly positive report – say, growth in the 165,000 range, as Wall Street Journal’s Marketwatch consensus expects, will raise questions about whether the current economic and regulatory climate will ever allow for the kind of recovery we saw in the 1980s, or for that matter, under George W. Bush after the 2003 recession.

If the White House doesn’t have any answers other than to point to Romney’s wealth and the Buffett Rule, Romney will be happy to discuss job creation and economic growth with voters instead.