This week, both Barack Obama and Republican presidential contender Mitt Romney put forward tax reform plans. Only one of them can be taken seriously, however. The Obama plan addresses tax issues substantively, backing up the proposals with documentation and analysis.

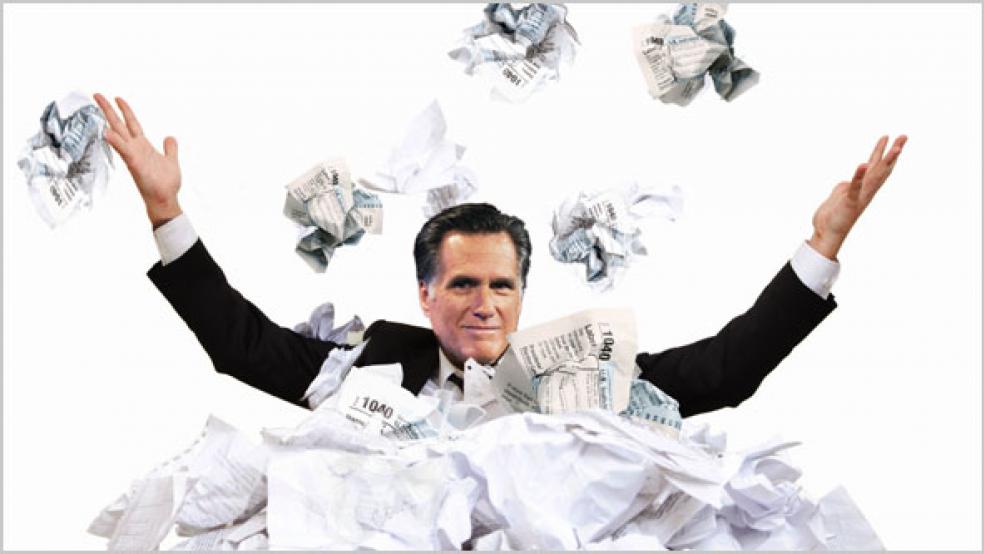

By contrast, the Romney plan is little more than a press release, lacking even the most basic information necessary to begin to evaluate it. This is not to say that one plan is per se good and the other bad; only that there is a major imbalance in terms of addressing complex tax issues in a way that tells us whether we can trust the author to implement meaningful tax reform.To begin with the Romney plan is only slightly longer than this column and consists largely of subheads with little in the way of actual text. Almost all of the text involves assertions that cannot be taken at face value.

For example, the Romney document implies that enacting his plan would create 2.5 million jobs. But if you read the document upon which this claim is based, it is an op-ed article claiming that “policy uncertainty” in all areas, not just tax policy, is holding back growth.

Moreover, one of the key policy uncertainties the article cites is uncertainty over whether the debt limit will be increased over Republican opposition. Yet Romney has lately been attacking former Senator Rick Santorum, one of his competitors for the GOP nomination, because he voted to increase the debt limit. Of course, it would be irresponsible for any president to allow the nation to default on its debt. At a minimum, it will add massively to the “policy uncertainty” that Romney claims that his tax plan addresses.

A key reason for tax cuts with expiration dates is to maintain the fiction that our fiscal problems are not as serious as they are.

Additionally, it’s worth noting that to the extent there is policy uncertainty in the tax area, it is because the tax cuts of the George W. Bush administration were originally enacted with expiration dates on them. They all expired at the end of 2010 and then were extended at the last minute for just two years. And of course the recent expiration of the temporary payroll tax cut, which unquestionably created significant uncertainty, was solely due to Republican resistance to its extension.

Undoubtedly the best thing that could be done in the tax area would be to stop fiddling with the tax code and make all of its provisions permanent. A vast amount of the complexity of the code comes from the annual expiration of the so-called fix for the Alternative Minimum Tax to keep it from taxing the middle class instead of the wealthy for whom it was originally intended; the research and development tax credit and many other provisions that have been expiring for decades and routinely extended.

A key reason for tax cuts with expiration dates is to maintain the fiction that our fiscal problems are not as serious as they are. Budget projections from the Congressional Budget Office are required to be based on current law. So if a tax cut is set to expire, it must assume that a de facto tax increase will take effect, even if it knows perfectly well that Congress will inevitably extend it.

Unfortunately, the lack of fiscal responsibility is the biggest problem with the Romney plan. While it claims that the proposed reduction in statutory tax rates for both businesses and corporations will be paid for with loophole closings and broadening of the tax base, it contains no specifics whatsoever. University of California economist Brad Delong calls this making policy through “magic asterisks.” It’s a reference to one of Ronald Reagan’s budgets that had a line in it for unnamed spending cuts, with an asterisk in place of an actual proposal.

In fairness, the Romney plan is no more fiscally irresponsible than those of his competitors for the Republican presidential nomination, according to a new report from the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. Only Ron Paul’s hopelessly unrealistic plan to slash spending far more than any Congress would ever enact avoids increasing the national debt substantially.

Turning to the Obama plan, it at least has the virtue of naming specific tax expenditures to pay for a reduction in the statutory corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 28 percent. It also makes some important points about the necessity of addressing some “sacred cows” in the tax code, such as the deductibility of interest by corporations, which has contributed heavily to excessive indebtedness.

The Obama report also makes the critical point that in comparing U.S. corporate rates to those of our competitors, it is essential to look at effective rates, which include the impact of deductions and credits, and not just statutory rates. The U.S. corporate tax system is not nearly as far out of line with other countries on that basis, which is why Republicans only talk about statutory rates, which are basically meaningless, economically.

On the negative side, Obama would institute an extra special low tax rate of 25 percent just for manufacturing corporations. As I explained, this is industrial policy at its worst and unlikely to be effective. It also moves in the opposite direction from tax reform, which ought to involve creating a level playing field for all businesses.

I think both the Romney and Obama tax plans are remiss in not addressing the central tax problem this country has, which is not enough revenue to fund the government under any realistic scenario. In my opinion, we can’t afford more tax cuts. While we need tax reform, it must be honest reform, with the sugar of rates cuts combined with the medicine of loophole closing.