|

What’s ahead for Federal Reserve policy in 2012? To answer that, it’s first important to note that the Great Recession and its financial crisis not only radically altered the conduct of Fed policy. They cast a spotlight on the institution like never before, opening it up to withering criticism from some areas of Congress and the private sector. The resulting post-crisis regulatory regime has in some respects changed the institution itself. It all presents an unprecedented set of pressures against which the Fed will be making policy decisions in the New Year.

The Fed’s 2012 policy committee should be a more cohesive group, following an unusual degree of internal discord in 2011 which added to the uncertainty in the financial markets over the direction of policy. The new makeup of next year’s committee, on which four presidents of the 12 district Federal Reserve banks rotate annually, should quell dissent. The three most hawkish voting presidents in 2011 who tend to favor tighter policy —Dallas Fed President Richard Fisher, Philadelphia Fed President Charles Plosser, and Minneapolis Fed President Narayana Kocherlakota—rotate off the committee.

That trio registered an unusual three dissenting votes from the seven-vote majority at the August and September meetings. The fourth—the dovish Chicago Fed President Charles Evans—dissented at the November and December meetings in favor of additional stimulus measures. The quartet of incoming voters promises to be a more centrist group, which will most likely mean less internal squabbling, although the new voices do not signify any shift in policy. “We continue to believe that, despite the chorus of voices on policy, Chairman Bernanke remains firmly in control of the committee and will continue to dictate the path of policy,” says UBS economist Drew Matus.

The Fed’s prime focus heading into 2012 will be a major change in its communications strategy. The policy committee, in coordination with a four-person subcommittee, has spent much of 2011 discussing ways to increase the transparency of Fed policy and more clearly communicate its policy thinking to the markets. These efforts are an offshoot of the extraordinary measures the Fed has needed to take in order to keep credit flowing and the economy growing. In the process, many investors and lawmakers have become uncertain of how much inflation the Fed is willing to risk in its efforts and whether it might be willing to risk a new asset bubble. The Fed would like to create more certainty in these areas.

Fed watchers think the communications initiative will involve three key changes, but they are unsure of just how much new clarity the effort will provide. Major elements are expected to be a specific numerical objective for inflation, periodic forecasts of the target federal funds rate, and an official statement of the Fed’s long-run policy goals. “We believe the Fed may be ready to move on these items early in 2012,” says economist Michael Gapen at Barclays Capital. The January 24-25 policy meeting would be an opportune time to reach both the markets and Congress. That meeting will include a press conference by Bernanke, and it occurs only a few weeks before Bernanke’s semiannual Congressional testimony on monetary policy.

Still, many market analysts remain skeptical about whether explicit targets or a greater volume of communication will improve the markets understanding of the rationale behind the Fed’s decisions. For example, the markets already accept the policy committee’s regularly published long-term inflation forecast as its de facto inflation objective, currently published at 1.7 to 2 percent. Plus, some worry that supplying more information would simply add to the confusion. UBS’s Matus fears that radically changing how the Fed communicates with the markets “could result in increased volatility as the markets learn how to understand the new dialogue.”

In perhaps the biggest change, the Fed is expected to begin publishing on a regular basis the committee members’ forecasts of the federal funds rate as part of its Summary of Economic Projections released at certain policy meetings. The Fed has already made a soft promise to keep the federal funds rate near zero until mid-2013, and there has been some discussion about tying changes in that rate to certain levels of unemployment and inflation. Chicago Fed President Evans has suggested holding the funds rate near zero until unemployment fall to 7 percent as long as inflation remains below 3 percent. Economists believe such a strategy would generate more questions than answers about the Fed’s intentions.

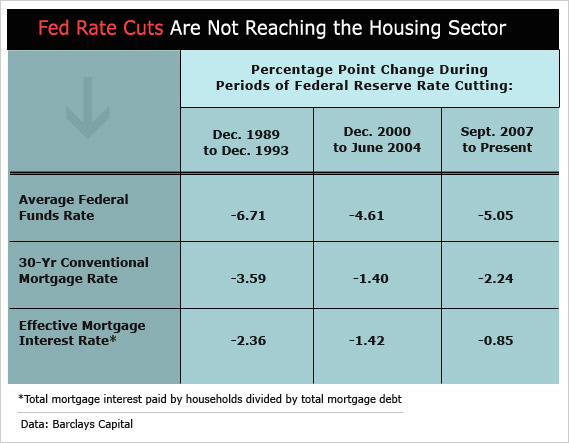

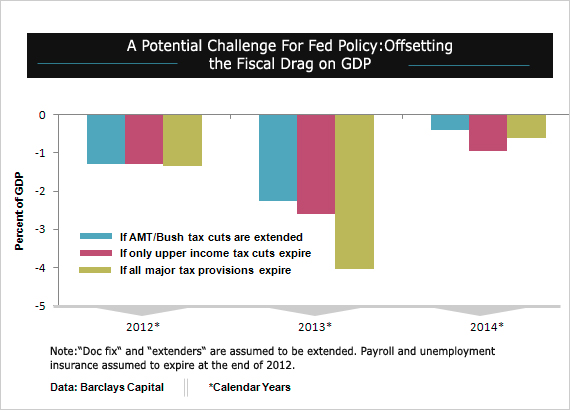

Given the improvement now underway in the economy, particularly in the labor markets, economists generally do not expect another round of asset purchases. However, a rising chorus of Fed policymakers has expressed concern that the depressed housing market is a major factor holding back the recovery and keeping unemployment high. Fed watchers are not ruling out the possibility of asset purchases geared toward mortgage-backed securities, but they also doubt the effectiveness of such purchases, given the unusual obstacles that are preventing the full effect of lower interest rates from boosting refinancing activity and home demand. New Fed action is fully expected should U.S. fiscal policy turn restrictive enough to threaten economic growth or if contagion from a financial meltdown in Europe were to spread to U.S. markets.

In the event of such a crisis, the Fed would face a new set of crisis management rules, set forth in the Dodd-Frank Act, but the new regulatory regime should not greatly hamper the Fed’s efforts to manage a crisis. The Fed must now provide only broad financial-system support, while no longer aiding any single institution. It must disclose the names of institutions receiving support, which could be counterproductive if a company is reluctant to take the aid for fear of appearing weak. And it must sign off with the Treasury and Congress for certain types of aid. “In our view, the more stringent requirements under the Dodd-Frank Act should not inhibit the ability of the Federal Reserve to establish emergency credit facilities if necessary,“ says Barclays Capital’s Gapen.

Over the next couple of years, as federal budget cuts make fiscal policy more restrictive to economic growth, the Fed will take on even greater policy responsibility for keeping the economy moving ahead. That’s challenge enough. Doing it under increased public scrutiny and a new regulatory framework will make the task even more difficult.