|

The stock market slump has given Americans yet another reason to feel lousy. It’s more than a struggling economy and high unemployment. The government is dysfunctional. The U.S. has lost its top credit rating. European financial markets are sending out bad vibes. All this has frightened investors and hammered stock prices, compounding fears of a double-dip recession and sending consumer confidence to levels not seen since the financial crisis. Will the stock market derail the recovery?

The market is likely to be on edge this morning after European stocks and the euro took a beating yesterday. Germany’s DAX index fell 5 percent after Chancellor Angela Merkel's Christian Democratic Union was trounced in state elections Sunday. Europe’s sovereign debt crisis and weak economic growth on both sides of the Atlantic continue to spook investors.

Worries swirled anew in the U.S. on Friday, when the Labor Dept. said job growth ground to a halt in August. Payrolls didn’t grow at all last month. The gains in June and July were less than first reported, and the jobless rate held at 9.1 percent. Although the Communication Workers of America strike against Verizon subtracted some 45,000 workers from payrolls, the August showing was still well below the 70,000 or so economists had expected. Stocks tanked, and the pressure on policymakers to act has ratcheted up. Wall Street will be listening closely to Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke’s speech in Minneapolis this Thursday for a sign of further policy action at the Fed’s Sept. 20-21 meeting.

Nobel Laureate economist Paul Samuelson said many years ago, “The stock market has predicted nine of the last five recessions.” Still, any big drop commands respect. At the close on Sept. 2, the Standard & Poor’s 500 index was down about 13 percent from its July 22 peak, having regained about a fourth of the nearly 17 percent drop from July 22 to Aug. 8. Big drops in the stock market destroy household wealth and create uncertainty, and uncertainty may well be more important right now. Economists have shown that consumers do not react to wealth losses all at once, with the effect on spending spread out over several quarters. The impact of heightened uncertainty, however, can be instantaneous. It can cause consumers and businesses to freeze in their tracks; that is, stop spending or stop hiring, which appears to have been the case for August payrolls.

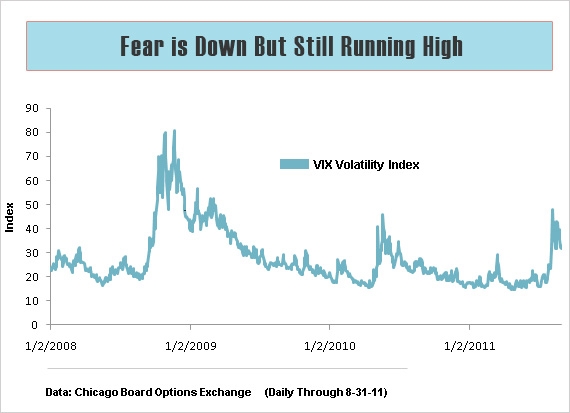

The best measure of market uncertainty is the Volatility Index, or VIX, calculated daily by the Chicago Board Options Exchange. Commonly called the fear index, it measures traders’ expectations for stock prices in the coming month. Big expected declines push the VIX higher—more fear. During August the VIX averaged 35, jumping from 19 in July. That’s above the level reached during last year’s round of European debt worries, when the index peaked at an average of 32 in May 2010. The VIX soared higher than 60 in both October and November 2008 after the collapse of Lehman Brothers.

A ten point rise in the monthly VIX level cuts

private-sector payrolls by an average of 74,000.

The VIX shows that fear is still running high, says Barclays Capital economist Troy Davig, but he notes it has reached the August level several times in the last 20 or so years without the economy turning down. “Uncertainly alone is unlikely to be sufficiently powerful to tip the economy into a recession,” he says. However, increased uncertainty can weigh on the economy. Companies can pay dearly for expanding into a new round of weakness, but the cost of doing nothing is small. Davig’s analysis shows that, historically, a 10 point rise in the monthly VIX level cuts private-sector payrolls by an average of 74,000 per month, which is in line with the August experience.

Davig says that uncertainty can affect hiring decisions but not necessarily firing activity . That appears to have been the case in August, given that weekly unemployment claims, which are an indicator of firing activity, continued to edge lower after adjusting for the effects of the strike. Looking ahead, there may be a silver lining in Davig’s analysis. The relationship also works the other way: Less uncertainty can have a positive impact. A more stable stock market in coming months could put companies in the mood to hire more workers.

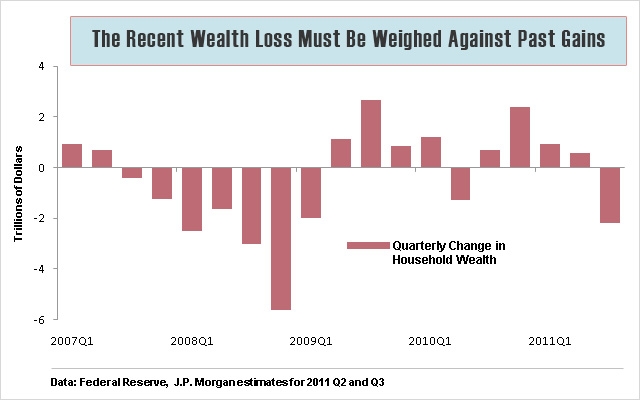

Stock market losses also cut into wealth, which has an impact on spending. Classic studies show that households spend about 3.5 cents of every additional dollar in wealth, defined as the value of total household assets minus liabilities. The reverse is also true. However, adjustments occur over a period of a couple of years. Economists at J.P. Morgan say about half the impact of a change in wealth occurs in the first two quarters with the rest occurring over the next six quarters. Households lost $16.4 trillion in financial and real estate wealth during the recession, but the impact on spending is now all but completed. Consumers have adjusted by reducing their debt and saving a much higher percentage of their income.

The estimated $2.2 trillion loss in wealth so far this quarter must be weighed against the $4 trillion or so increase from the fourth quarter of 2010 to the second quarter of 2011. J.P. Morgan analysts say the net effect is that household wealth is no longer adding to the growth in spending, but neither is it subtracting from growth. Barring a quick resurgence in stock prices, they say, that leaves a bigger burden on labor income to support spending, which is a new concern given stagnant August payrolls.

Through August, there are some hopeful signs. Car sales held steady, as did weekly measures of retail sales, with stores reporting good back-to-school activity, suggesting that consumers did not suddenly slam on the brakes last month. Plus, with gas prices already down more than 8 percent from their May high, and expected to fall further, lower overall inflation will help to support the buying power of household incomes. In coming months, though, much of the outlook for consumers—and the economy—will depend on how businesses respond to the new uncertainty now weighing on their hiring and firing decisions.