American businesses are fed up with Washington’s budget circus and the squabbling over raising the debt ceiling and a plan to assure future fiscal stability. When 470 CEOs sign a letter to the White House and Congress telling lawmakers to get their act together, it’s clear that business leaders are worried. The problem for the economy is that Washington’s paralysis is also paralyzing the business sector. Growing uncertainty has created a new round of corporate caution that is reducing the chances for stronger hiring and economic growth in the second half.

Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke echoed the popular line among economists when he told two Congressional panels last week that the first-half slowdown was the temporary effect of higher gas prices and supply disruptions after Japan’s earthquake and tsunami. Once the effects of those shocks passes, he said, he expects stronger economic activity and job creation. However, surprisingly pale reports on jobs and retail sales in June and July consumer sentiment suggest the economy’s vital signs are getting weaker not stronger, raising questions about the second half outlook.

Businesses hate uncertainty. It complicates planning, lessens willingness to commit funds to expansion, and—most important—puts a damper on hiring. The debt ceiling issue, while urgent, is only a small part of that uncertainty. Wall Street and political analysts generally believe lawmakers will not be so reckless as to fail to raise the debt limit. Any agreement, if only on that front, would avoid the sharp federal cutbacks and financial market turmoil that economists believe would lead to another recession. The 470 CEOs in their letter to policymakers said that, even in the absence of a debt ceiling crisis, what they need in making plans to invest and hire is confidence in the future regarding government policy.

A sigh of relief over the debt ceiling, by itself, will not alleviate business or financial market concerns. That’s because it will do nothing to answer the greater questions about when and how Washington will address its long-term fiscal instability and how those actions will affect the economy. The rating agencies put it more bluntly than the CEOs. On July 14, Standard & Poor’s, following a similar move by Moody’s, warned that there is a 50-50 chance it would downgrade the U.S.’s credit rating from AAA to AA if lawmakers “have not achieved a credible solution to the rising U.S. government debt burden and are not likely to achieve one in the foreseeable future.”

The new concern for the rest of this year is the impact of business uncertainty on the job market. In June, job growth ground almost to a halt, and the unemployment rate continued to rise. Economists at Barclays Capital see a clear correlation between uncertainty and job creation. Barclays economist Troy Davig says heightened uncertainty results in a wait-and-see effect that depresses hiring. “A real risk to the labor market is if the current debt ceiling negotiations, while avoiding default, fail to deliver a comprehensive fiscal agreement,” he says.

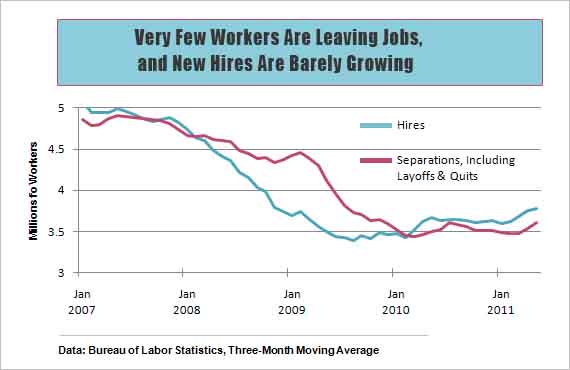

It’s not that companies, on the whole, face any great need to lay off workers and cut costs. They have already done that, and continue to reap the resulting rewards of higher profit margins and cash reserves. Companies just aren’t hiring. June’s negligible 18,000 increase in payrolls was the net result of about four million people hired and about the same number leaving work, either voluntarily or by layoff. Over the past year layoffs are down 2.3 percent, but gross hiring is down by an even greater 6.4 percent. “Businesses have the capacity to hire more aggressively but are holding back out of nervousness about policy,” Moody’s Analytics chief economist Mark Zandi says in a recent report.

Businesses are losing faith in both the economy and Washington policymakers. The Conference Board’s index of CEO confidence tumbled in the second quarter. The Board said only 33 percent of the execs surveyed said business conditions were better than they were six months ago, down sharply from 85 percent in the first quarter. “Expectations are that this slow pace of economic growth will continue,” says the Conference Board’s Lynn Franco. Just 43 percent of the CEOs foresee improvement in economic conditions over the next six months.

Small companies are also downbeat—and more vocal. A Chamber of Commerce survey shows that 84 percent of small companies believe the economy is “on the wrong track,” and 64 percent say they are not planning to hire this year. The Small Business Optimism index, compiled by the National Federation of Independent Business fell in June for the fourth consecutive month. “Small business owners are registering a vote of no confidence in the federal government,” says NFIB chief economist Bill Dunkelberg.

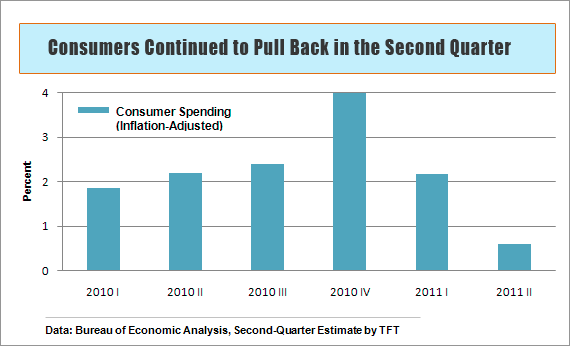

New caution on hiring puts consumer spending at risk. June retail sales were weaker than economists had expected, even after accounting for weaker gas station receipts due to lower gas prices, and the University of Michigan's index of consumer sentiment plunged in early July. Real consumer spending last quarter, to be reported with second-quarter GDP on July 29, appears to have grown at barely more than a 0.5 percent annual rate last quarter. That would be the weakest quarter since the economy was in the recession two years ago.

For the third quarter, consumer spending is expected to pick up, reflecting a lift to the buying power from the drop in gas prices, and auto production is rebounding from second-quarter supply disruptions. “To be sure, both of these positives are looking less shiny than they did a few weeks ago,” says J. P. Morgan economist Michael Feroli. But a new problem is shaping up. Unexpectedly weak spending appears to have caused an unwanted buildup of inventories that companies will have to work off this quarter, a process that will depress output and GDP.

Consequently, J.P. Morgan has revised down its outlook for third-quarter GDP growth, from 3 percent to 2.5 percent, a pace that would not imply a big rebound in job growth. Economists, including the Fed’s Bernanke, have been counting on pickups in consumer spending and auto production to generate stronger GDP growth this quarter. If that doesn’t happen, the reason may be a growing sense in the business community that policymakers are placing a veil over the economy’s future instead of providing guidance.