|

Fiscal stimulus doesn’t last forever. At some point, the economic boost from temporary increases in government spending and one-off tax cuts goes away, placing a greater burden on the private-sector to generate growth and create jobs. This time, with the economy still wobbly, the impact could be jarring. The loss of stimulus starting next year will depress economic growth and complicate the Federal Reserve’s efforts to shift monetary policy to back to normal.

Friday’s shockingly weak jobs report highlights the economy’s vulnerability and emphasizes the danger of Washington doing too much budget cutting, too soon. Job growth all but ground to a halt in June, as payrolls increased by a slim 18,000 workers and the unemployment rate rose to 9.2percent. “All in all, an employment report with no redeeming features whatsoever,” says Barclays Capital economist Peter Newland. The labor market’s turn for the worse may even shift the budget negotiations toward the need to extend some current programs or to propose new actions that would provide additional economic stimulus.

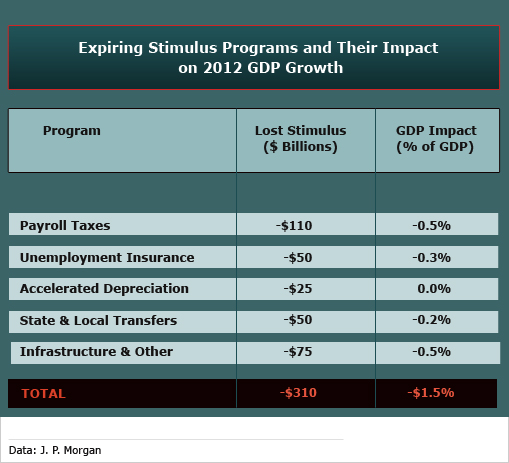

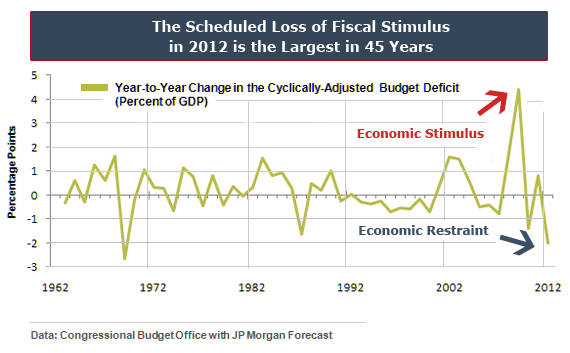

When 2012 begins, the economy is already scheduled to lose more than $300 billion in federal support, as several programs aimed at propping up growth in recent years expire or fade away by the end of this year. Policy changes now on the books will result in the most severe fiscal tightening in more than 40 years, subtracting an estimated 1.5 percentage points from GDP growth next year, according to an analysis by economists at J.P. Morgan Chase. That does not include any additional drag from new spending cuts or tax increases that might emerge from the budget talks on Capitol Hill or from cutbacks by state and local governments.

Expiring programs will help to reduce 2012 deficit but at a heavy cost to the economy, especially in the first half of the year. So far the private-sector, which has grown by a modest 2.9 percent over the past year, has not shown the oomph needed to absorb a 1.5 percentage point hit to GDP growth while also supporting a growth rate strong enough to reduce unemployment. For example, for the economy in 2012 to make the mid-point of the Federal Reserve’s 3.3-to-3.7 percent growth projection, private-sector GDP would have to grow 5 percent, a pace not achieved since the tech-stock boom more than a decade ago.

The known drags set to arrive next year start with the expiration at the end of 2011 of the 2 percent reduction in employee payroll taxes. The tax break, which began in January 2011, helped households cope with surging gas prices. Its elimination will be the biggest single burden, soaking workers for an extra $110 billion in withheld taxes beginning in January. The reduction in spendable income will hit consumer spending—and GDP growth—hard in the first quarter.

The end of emergency unemployment benefits at year-end will take away $50 billion, as will fading aid to state and local governments. Federal infrastructure spending will fall about $75 billion next year, and businesses will cough up an additional $25 billion as this year’s temporary provision allowing 100 percent expensing of certain capital expenditures changes to only a 50 percent allowance. All this adds up to $310 billion, which the J.P. Morgan analysts believe is a conservative estimate. The current budget talks are multi-year and not focused on 2012, but some lawmakers are pushing for broader and immediate spending cuts that would only add to next year’s fiscal restraint.

The Fed and most economists believe this year’s first-half slowdown is a temporary downdraft caused by surging gasoline prices and supply disruptions resulting from the earthquake and tsunami in Japan. The economy grew at an annual rate of only 1.9 percent in the first quarter, and second-quarter growth struggled to match even that tepid pace. Economists expect growth to pick up now that the first-half depressants are abating, but the unexpectedly weak jobs report for June raises new doubts about second-half growth prospects.

Heavy fiscal drag would put policymakers at the Fed between a rock and a hard place. Inflation outside of energy and food is already creeping up, but without a robust private sector, the unemployment rate may not reach the 8 percent mid-point of the Fed’s 7.8-to-8.2 percent forecast range at year-end 2012. At the least, most Fed policymakers would be reluctant to begin raising interest rates amid prospects for a stubbornly high jobless rate, and they could even face pressure to begin a third round of quantitative easing, involving securities purchases, to keep rates low. Plus, the longer the Fed keeps U.S. interest rates on hold, as central banks in Europe and elsewhere raise rates, the more downward pressure on the dollar.

Fiscal restraint goes far beyond Washington. State and local governments have already axed more than 500,000 jobs over the past three years. Economists at UBS project another 450,000 losses in the upcoming 2012 fiscal year, which began on July 1 for most states, but they are watching a trend that could lessen that total. UBS economist Maury Harris notes several key states and cities in which public-sector unions have made concessions. “Elected officials appear to be responding to very strong public sentiment against laying off critical public-sector employees, including teachers,” says Harris. Still, job losses in 2012 will likely top the 300,000 cuts in 2011.

There is no question that the U.S. faces at least a decade-long period of fiscal austerity. But in the coming year, amid prospects that the economy will be losing momentum, economist David Hale of David Hale Global Economics says the new obsession with deficits is overwhelming the potential need for policies that would protect the economy. “The question that has not been asked is whether the fiscal drag should be so frontloaded as to jeopardize the economy’s recovery in an election year,” says Hale. “Such a risk now clearly exists in 2012.”

More about the economic outlook from The Fiscal Times:

Economic Perfect Storm Halts Consumer Spending

The Job Delusion - Growth is Just around the Corner

Will Higher Taxes Tank the Economy?