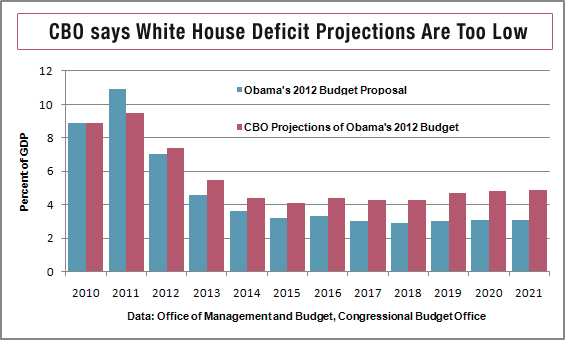

Obama’s budget credibility took a hit from the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office this month, when CBO said the administration’s 2012 budget proposal will not deliver the deficit improvement in the coming decade that it promised.

CBO’s analysis said deficits through 2021 would total $2.3 trillion more than those projected in the budget document prepared by the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB). Instead of falling to 3 percent of GDP by 2017 and remaining near that level through 2021, CBO analysts say the deficit would never go below 4.1 percent of GDP and would begin to rise toward the end of the period, hitting 4.9 percent in 2021.

The analysis will add fuel to the Republican’s fire as the Washington budget battle heads down to the wire — again. In lieu of an official budget, the latest in a series of temporary spending bills that have kept the government operating will expire on Apr. 8. President Obama will have to negotiate a deal with House Republicans who want $61 billion in spending cuts in order to keep the government running until the end of the current fiscal year on Sept. 30. Still, Obama’s bigger challenge will be the hard choices facing the 2012 budget and new pressure to reduce future deficits.

The projected failure to reach 3 percent of GDP is important. At that level the so-called “primary budget,” which excludes interest payments, is in balance. A deficit maintained at that level typically means that debt held by the public is not growing any faster than GDP. The administration’s numbers show public debt stabilizing at about 77 percent of GDP, but CBO projects the White House’s proposals would double the debt by 2021, causing a steady rise to a hefty 87 percent of GDP, up from 62 percent in 2010.

CBO’s projections differ from those of the OMB for two broad reasons. First, there are differences in the underlying forecasts of what would happen without any of the proposals in Obama’s 2012 budget; that is, if current policy was unchanged for the next 10 years. That difference accounts for some $1.3 trillion of the $2.3 trillion disparity, due in large part to the administration’s more upbeat forecast for economic growth. The White House sees growth averaging 3.9 percent per year over the next five years vs. CBO’s 3.3 percent. The other $1 trillion reflects differing estimates of the cost of new programs and savings on existing programs.

Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) recently issued a quid pro quo linking GOP support for raising the $14.3 billion statutory ceiling on federal debt to Obama’s agreement to long-term spending cuts that would address the unsustainable path of fiscal policy. The Treasury Dept. says the debt limit will be reached between Apr. 15 and May 31. Economists have warned that market reaction to hitting that ceiling could harm the economy, if holders of U.S. Treasury securities demand higher yields out of uncertainty over the government’s ability to function and meet its obligations.

If McConnell and the GOP are able to bring Obama into a discussion of long-term deficit reduction, the national debate over taxes and entitlement programs will ratchet up several notches. “The policy changes that are needed will significantly affect popular programs or people’s taxes or both,” said CBO Director Douglas Elmendorf at a policy conference in early March. On the revenue side, taxes on individual income and social insurance account for more than 80 percent of all revenues. As for spending, annually funded discretionary programs outside of defense are only 19 percent of all outlays and cannot alone solve the problem, which means mandatory entitlement programs will have to be a part of any solution.

The Breakdown of Federal Outlays, 2010 | |||

Federal Outlays | Percent of Total | ||

Mandatory | 55% | ||

Defense | 20% | ||

Nondefense Descretionary | 19% | ||

Interest | 6% | ||

Mandatory Outlays | % of Mandatory* | ||

Social Security | 97% | ||

Medicare | 23% | ||

Medicare & Other Health | 15% | ||

Other Mandatory | 16% | ||

Unemployment Compensation | 8% | ||

| Data: Congressional Budget Office * Numbers don't add up to 100% due to rounding | |||

One proposal, from Senators Bob Corker (R-TN) and Claire McCaskill (D-MO), would cap federal outlays at just over 20.6 percent of GDP in 10 years, compared with 24.7 percent currently. That’s a tough goal. Even under an extension of current law, ignoring Obama’s 2012 budget plans, only a handful of programs — Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid and other health programs, defense, and interest — would exceed total revenues in only five years. Elmendorf says such a cap would require cuts in at least one of these major programs, even if everything else the government does is totally eliminated.

It’s not just how much and where to cut, but also when to cut. Beginning actual budget cuts quickly has advantages and disadvantages, according to CBO. Fast implementation would lift national savings, cut future interest costs, allow greater flexibility to address new problems, and reduce the chances of a fiscal crisis in which investors lose confidence in the U.S. and push borrowing costs higher. However, rapid action would also cut deeper into economic growth and employment, while hitting older Americans’ benefit payments with little time for them to adjust. More gradual implementation would generally reduce the advantages, but mitigate the disadvantages.

Regardless of how fast the policy changes are actually implemented, simply putting a plan into law sooner rather than later would have key benefits, CBO says. Authorizing a course of action quickly would allow gradual implementation of the plan before the problem intensifies, requiring faster and larger cuts. “Moreover, enacting policy changes soon would probably provide some boost to economic activity by reducing uncertainty and holding down interest rates,” says Elmendorf.

Overseas investors, who hold 48 percent of all Treasury securities, continue to watch the budget battle for signs that the U.S. is committed to fiscal stability. The problem is the battle comes down to ideology regarding the size and influence of government at a time when liberals and conservatives are more polarized than ever. “Compromise has become a dirty word,” says Stuart Rothenberg, editor of the Washington-based Rothenberg Report, a non-partisan newsletter. What politicians seem to be ignoring is that when ideology goes up against the financial markets, the markets always have the last say.

Related Links:

Six Scary Inarguable Truths About the New Red Menace (Investors Business Daily)

Federal Debt Held by Public to Top $20 Trillion by 2020 (New American)

Shutdown Looms Over U.S. Budget (Pittsburgh Post Gazette)